The crack of the pistol shot was still ringing out across the serene waters of Middle Harbour when Alfred hit the ground, felled by the force of the bullet. The crowd happily mingling at Sydney’s Clontarf Reserve turned in horror. “The Duke is shot!” someone shouted. “He is shot and has fallen down dead.”

His Royal Highness, Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh and beloved second son of Queen Victoria, had indeed been shot – in the back and at close range. The man holding the smoking Smith & Wesson was Henry O’Farrell. As the crowd stood aghast, O’Farrell levelled his revolver and took aim a second time.

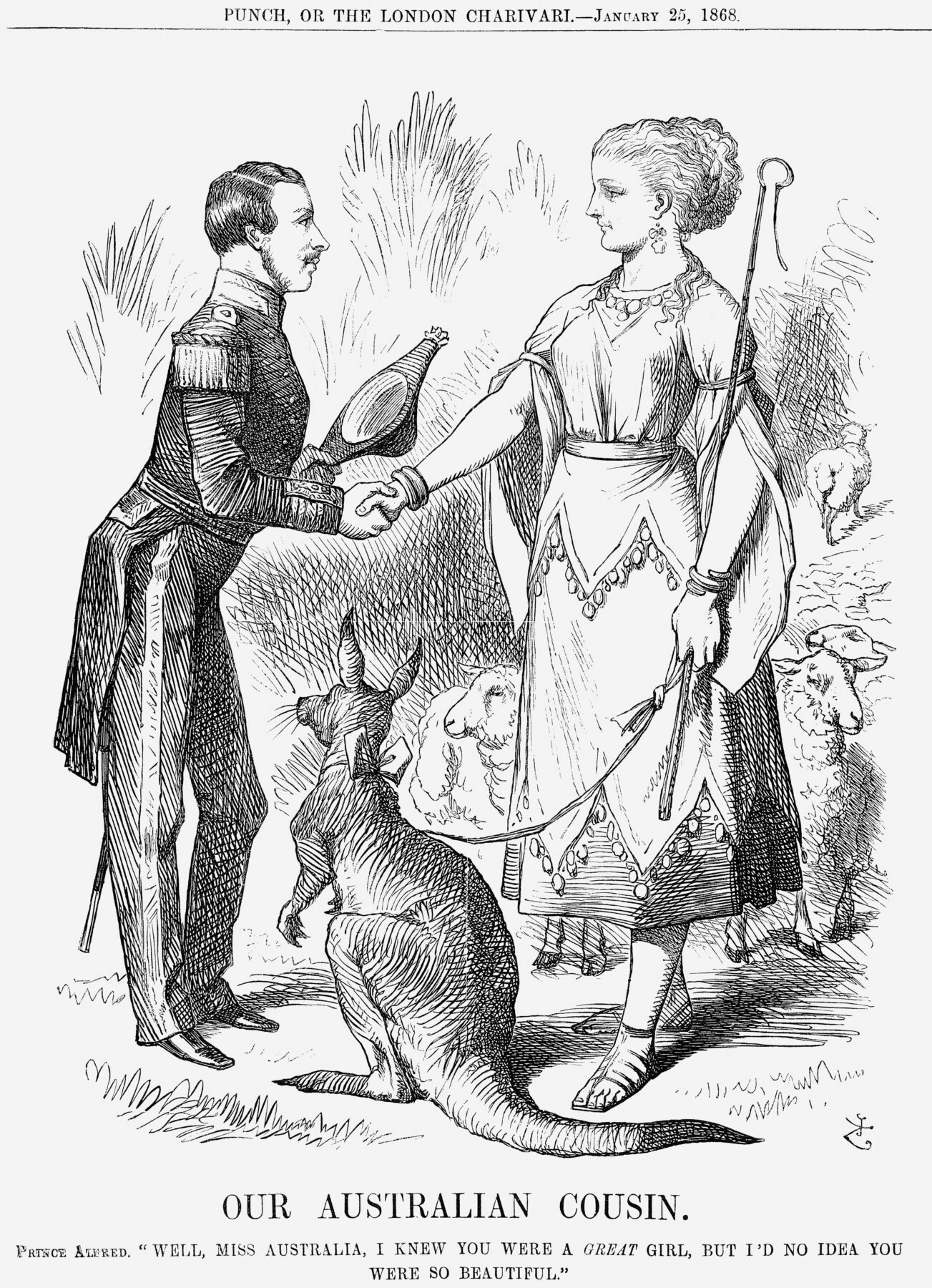

Everything changed in that moment. It was 12 March 1868, and the Duke – ‘Affie’ to his mother – was on the first royal visit to the British Empire’s antipodean possessions. Australia at that time was a fledgling collection of colonies, trying to prove it could stand on its own two feet but still in need of the protection afforded by the Royal Navy. Westminster was wary of losing more of its far-flung outposts – the Indian Mutiny was within recent memory, and the Dominion of Canada had confederated only the previous year – and desired to bolster the loyalty of its overseas subjects by lavishing them with some attention. There was already talk of an Australian republic, but also some support for a monarchy of its own. It was even mooted that the first ‘King of Australia’ might be young Affie.

Royal behaviour

The Queen was an astute ruler. The 23-year-old Alfred liked to live life large, harking back to a time when royals could do as they damn well pleased. However, by the mid-19th century, those days were well and truly in decline and the first family was expected to behave with decorum. Alfred had gained a reputation as an enthusiastic socialite and ladies’ man, and Queen Victoria orchestrated the 18-month voyage south to remove him from the bad influence of his elder brother, Crown Prince Edward, and the brothels of Paris. She hoped he’d return a more mature personage.

HMS Galatea formally landed at Glenelg, South Australia, on Halloween 1867. The country was already wild with royal fever, each colony trying to outdo the others in their displays of loyalty to the Crown. Queen Elizabeth II’s visit almost a century later, in 1954, paled in comparison. The recent tour, in 2024 by King Charles III, wouldn’t have even registered.

Prince Alfred had little interest in the affairs of state, although he performed them dutifully. His appetite was for other sorts of affairs. Indeed, polite society was quietly outraged by his laddish behaviour. Suffice to say that some wags stole a signboard reading “By appointment to His Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh” and nailed it above the door of their city’s most prestigious brothel. By the time Alfred arrived in New South Wales after six weeks in Victoria, and with his favourite courtesan in tow, there was a current of disgust pulling within the tidal wave of devotion.

The schedule of events in Sydney was packed, notably including a cricket match between the Aboriginal XI – which was about to depart on an historic first tour of England (see Our summer obsession, page 84) – and an Army and Navy XI team. A fundraising picnic for the Sailors’ Home was organised at Clontarf Reserve, where members of the public could, for a guinea each, mingle with the royal party. Despite recent outbreaks of sectarian violence, Alfred declined any personal guard beyond the 12 police constables assigned to the event. In retrospect, it was perhaps not the wisest decision.

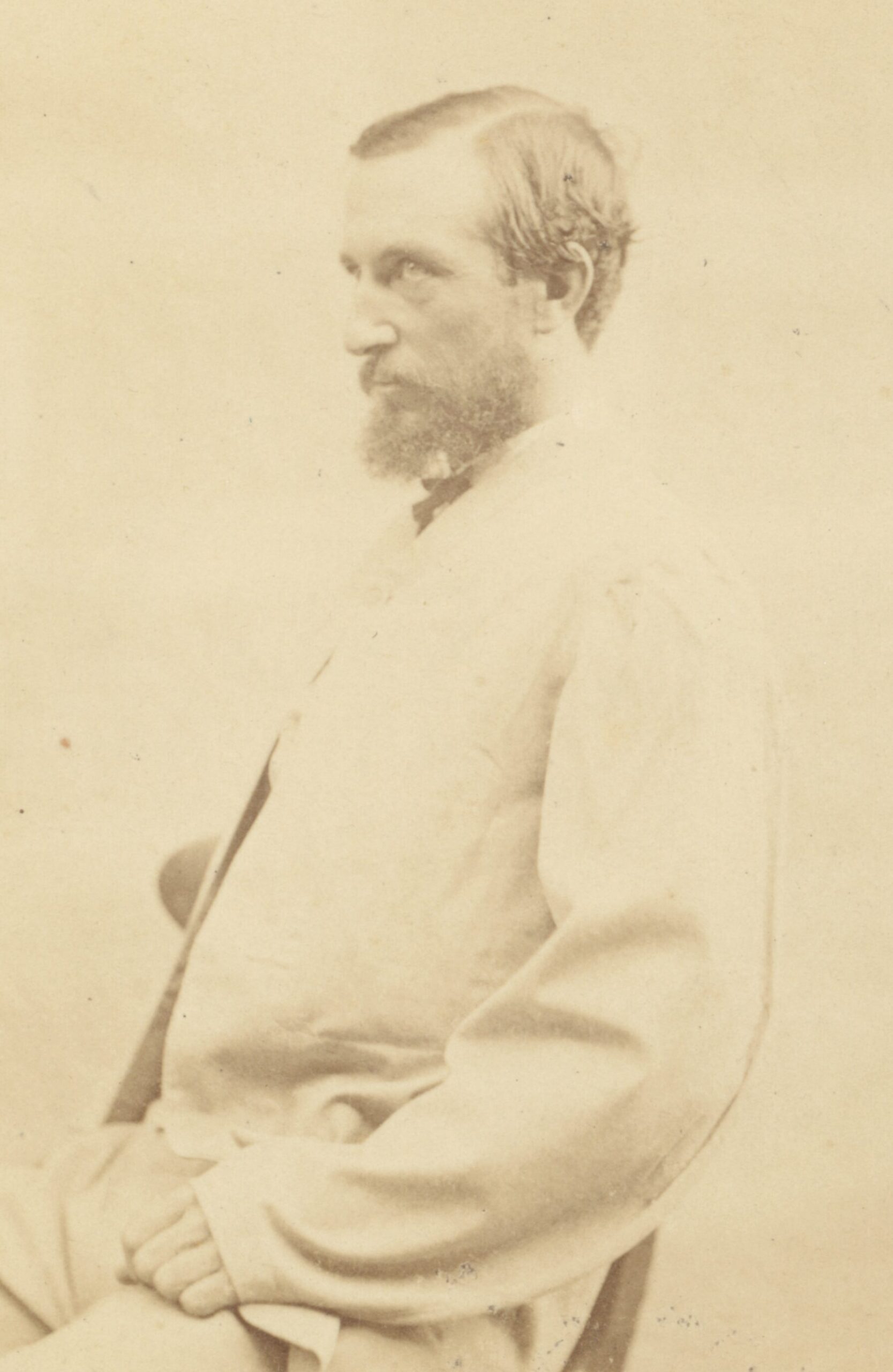

Among the crowd that Thursday afternoon was a well-dressed Irishman with two guns in his pocket. Henry O’Farrell, aged 35, was on a mission. Born in Dublin, his family emigrated first to Liverpool on the eve of the Irish Potato Famine; then, in 1841, hoping to escape the continued religious and racial persecution there, they bought passage to Port Phillip, Victoria, on the other side of the world.

Unfortunately, even in Australia the Irish were considered the lowest class of immigrant, and Catholicism widely regarded as a dangerous disease that ought to be exterminated. In this atmosphere, young Henry’s wish was to join the priesthood, and at 19 he was ordained as a deacon and sent to Europe to finish his religious education. Somehow, among the ancient colleges of learning, things came unstuck; Henry fell off the chastity wagon and returned home disillusioned, rapidly devolving from upstanding youth to borderline alcoholic.

As global anti-Irish sentiment grew, so did Irish designs on a republic of their own, and the next decade brought a period of intense political turmoil. By the time of the Duke’s visit, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their US counterparts, the Fenian Brotherhood, had emerged with the goal of ending British rule in Ireland via armed revolution.

By then, Henry was frequently described as mad and dangerous. He’d spent time in asylums during bouts of delirium tremens (caused by alcohol withdrawal) and epilepsy, and was known for sleeping with pistols, threatening to kill his friends and preaching pro-republican rhetoric. Abraham Lincoln had been famously assassinated in 1865, and Thomas D’Arcy McGee, one of the architects of Canadian Confederation, was shot dead by a Fenian sympathiser only five weeks earlier. It was a time of protest by public murder, and Henry O’Farrell was inspired.

On the morning of the picnic, Henry was relaxed but staunch. He’d written to two Irish newspapers announcing his intentions, knowing the letters wouldn’t arrive until after the fateful day. The political atmosphere was positively green – St. Patrick’s Day was imminent, and three IRB members, known as the Manchester Martyrs, had recently been hanged for murder back in England. Even the name Clontarf was portentous, taken from a 1014 battle in which the Irish were victorious against the Vikings.

After some Dutch courage in the refreshment tent, O’Farrell strode up behind his target and, from two metres away, pulled the trigger – crack!

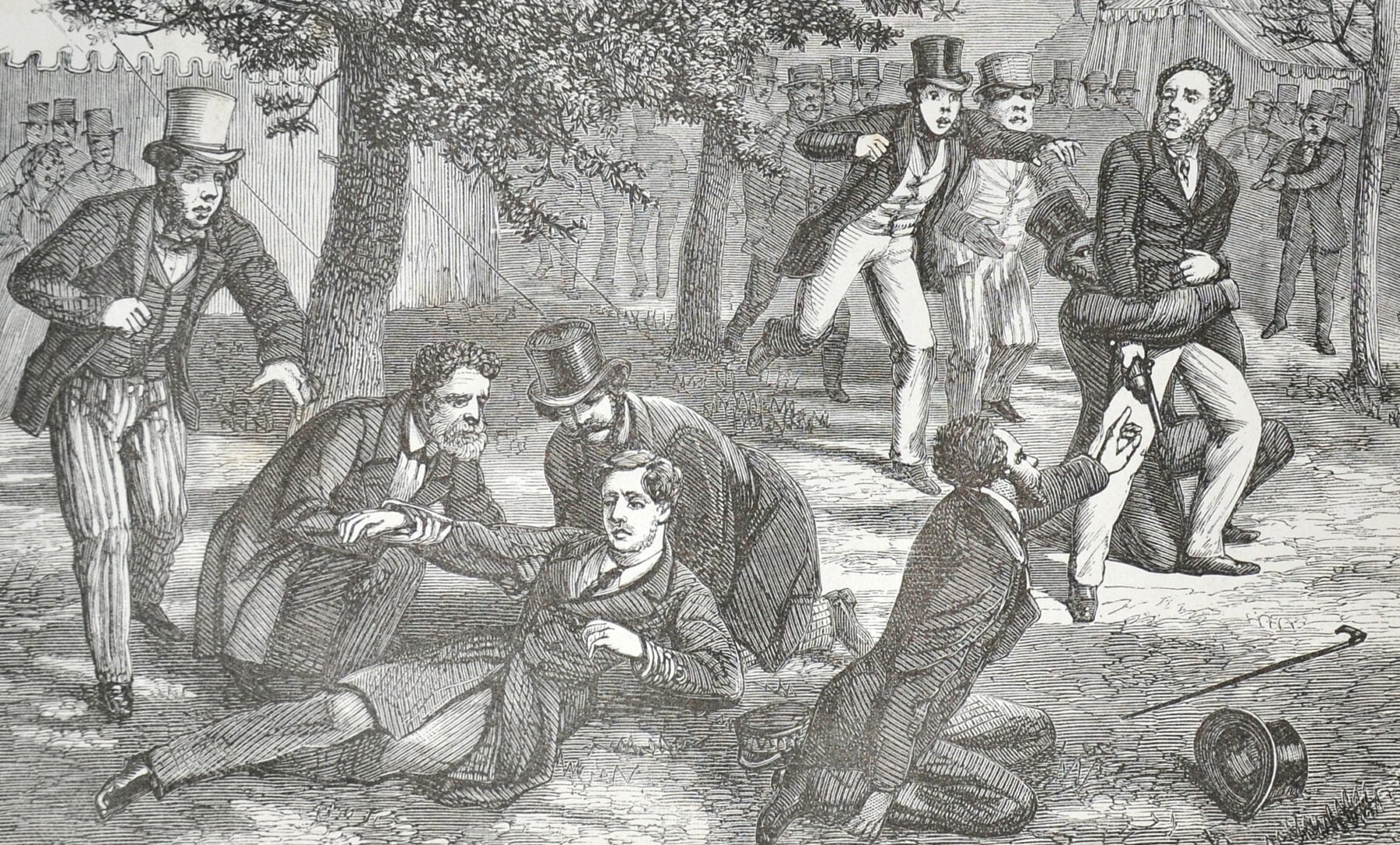

A swift trial

O’Farrell’s second shot misfired and the third went astray as he was tackled to the ground, the bullet hitting a bystander in the ankle. All hell broke loose. The crowd’s fear for the Duke’s life was overtaken by their hatred of his would-be assassin, who was set upon by a lynch mob. He was beaten senseless and a rope was readied for his neck – until Police Superintendent John Waisthall Orridge intervened, managing to distract the crowd while the object of their wrath was dragged to safety.

Meanwhile, the victim had been carried to the ladies’ tent and tended to by two of Australia’s first contingent of Florence Nightingale-trained nurses. Incredibly, the lead ball had been deflected by the rubber of his sturdy braces and diverted through his lower back, missing his spine,

ribs and internal organs, and lodging below his right nipple. He would live!

The fallout was considerable. Australia united in an orgy of shame and contrition that such an atrocity had been committed on the country’s soil. Mass indignation meetings were held to display renewed allegiance to the crown, and emergency legislation was passed to outlaw any expression of disloyalty as sedition, punishable by life imprisonment. Even refusing to join a toast to the Queen was deemed treasonous, and seemingly every male baby born for months afterwards was named Alfred.

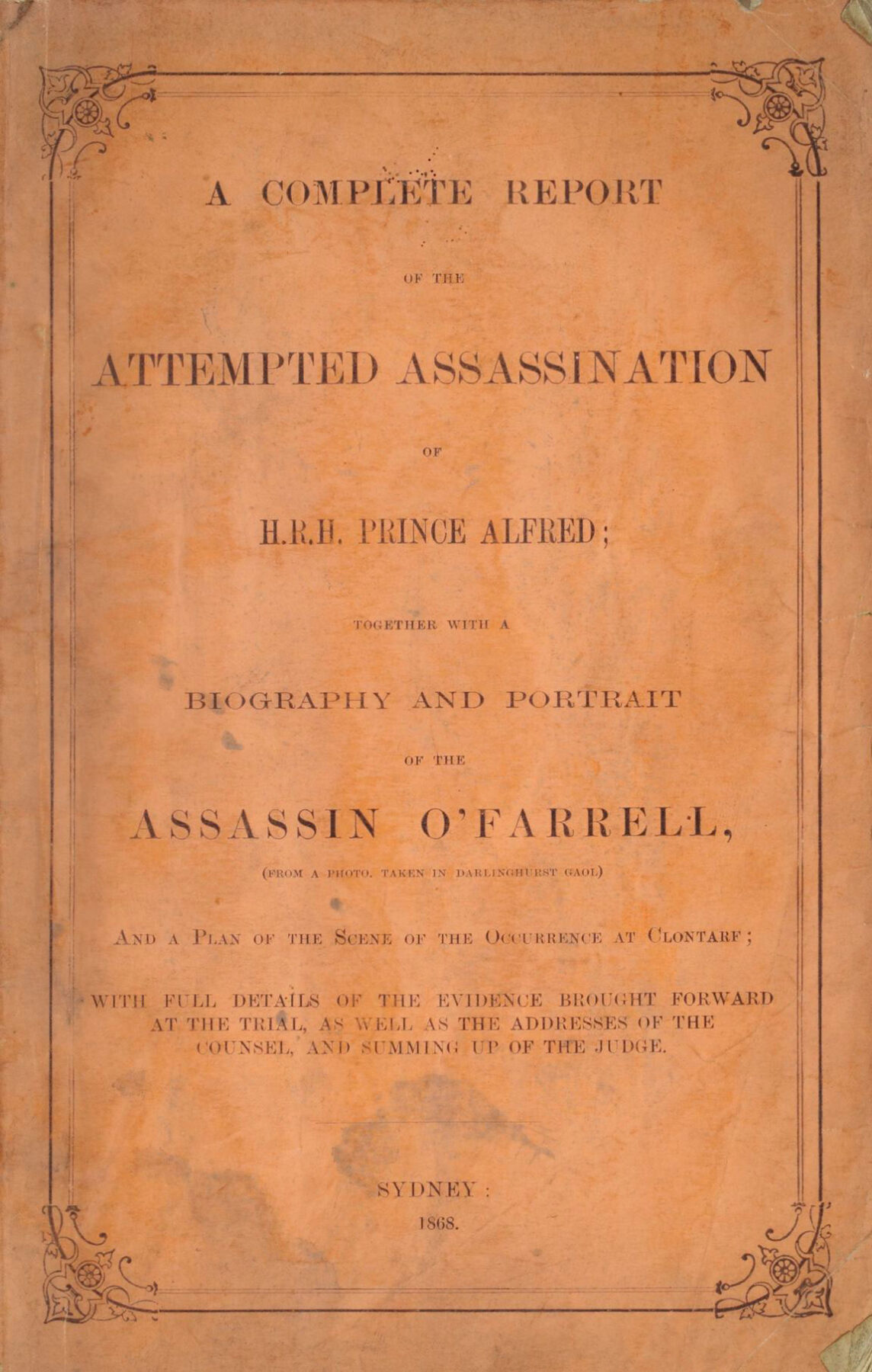

O’Farrell’s trial was swift, merciless, and regarded by modern historians as a miscarriage of justice. He initially claimed he was part of a Fenian conspiracy and had been chosen by poll to do the deed, but no co-conspirators ever materialised and he later admitted this was a lie.

The defence case was based on a plea of insanity – probably accurate, given O’Farrell’s history – but time wasn’t allowed for key witnesses to travel from Victoria. The prosecution allegedly hid evidence and, in the prevailing mood of society, the jury was anything but impartial.

It took just 54 minutes for the defendant to be found guilty before he was sentenced to death. Henry’s sister Caroline Allan appealed to the Governor of NSW, Lord Belmore, for clemency. After all, the crime of ‘wounding with intent to murder’ was no longer a capital offence in any other Australian colony, or even back in Britain. She also wrote directly to Alfred, who nobly requested a stay of execution until the case had been put before his mother.

It was to no avail. Lord Belmore’s was the final decision and the sentence was to stand.

Henry O’Farrell was hanged at Darlinghurst Gaol on 21 April 1868, a mere 40 days after perpetrating the crime, and buried at Rookwood Cemetery. He was reported by The Sydney Morning Herald to have walked the scaffold “cool, calm and collected”, perhaps looking forward to meeting the saints at last.

Alfred set sail for England a few days before the execution. With his shooting, the tour had been saved and hailed a tremendous success rather than an embarrassment. All the Duke’s past indiscretions were forgotten, but so was any suggestion that Australia was ready for independence.