Australia and cricket have gone hand in batting glove virtually ever since Arthur Phillip set sail from Portsmouth in 1787 – the same year the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) was formed. And while Australia has a host of winter football codes battling for supremacy, there’s only one summer game.

That game takes many forms. At the top there’s Test cricket, the Big Bash and the first-class game, for example. There’s grade cricket most weekends from September to March across the length and breadth of the nation. Then there’s the traditional backyard game on Christmas Day with assorted local rules: one bounce, one hand; only two short-pitched deliveries per over to Grandma; or ‘electric-wicky’. Or even beach cricket, from Byron Bay to Palm Cove, Cable Beach or Glenelg. And yes, the pet dog can play too.

Wherever you look in Australia, cricket reigns supreme. It has pride of place all the time the sun shines, and even when the occasional rainstorm obscures the view of the stumps being blown halfway down an astroturf wicket – while batters and fielders alike shelter under a makeshift gazebo. It holds the attention and affection of so many Aussies. It’s a sport that has made heroes through the ages, thrust young men and women into the limelight, and elevated the respective position of captain of Australia to rival that of Prime Minister – and in some cases, way above.

Modest beginnings

The game, however, sprang from humble beginnings. While ad-hoc games would undoubtedly have taken place beforehand, the first recorded match (according to the Sydney Gazette and NSW Advertiser) in Australia took place at Hyde Park, Sydney, on 8 January 1804 between the officers and crew of HMS Calcutta. It was regarded as recreational, with four-ball overs and heavy bats the norm, but played under the English laws of the game.

As the game blossomed, a government decree in October 1811 outlined the boundaries of Sydney Common, later Moore Park and the SCG. Popularity grew; Governor Macquarie even ordered a bat from Britain for his son. An article in The Australian noted a match on 7 August 1826 that led to the idea of forming “The Australian Cricket Club”. The problem was finding decent opposition; no-one was able to defeat them until 1830, when a team based in Campbelltown finally came away with victory.

That year also saw significant fixtures between military and civilians, attracting spectators and a £300 prize. The first-known laws had been drafted in 1744, codified in 1774, and first issued by the MCC in 1788. Cricket in Australia followed these, but the Melbourne Cricket Club’s decision in 1838 to adopt MCC laws confirmed their authority.

The status of the game grew. The first overseas touring side, led by H.H. Stephenson of Surrey, arrived in 1861–62. Twelve professionals sailed from Liverpool, arriving in Melbourne on Christmas Eve. Sponsored by caterers Spiers and Pond, the tour promoted both their business and the game’s popularity. Victoria lost heavily to the tourists at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, as did all opponents, but massive crowds – about 15,000 in Melbourne – made it a huge success.

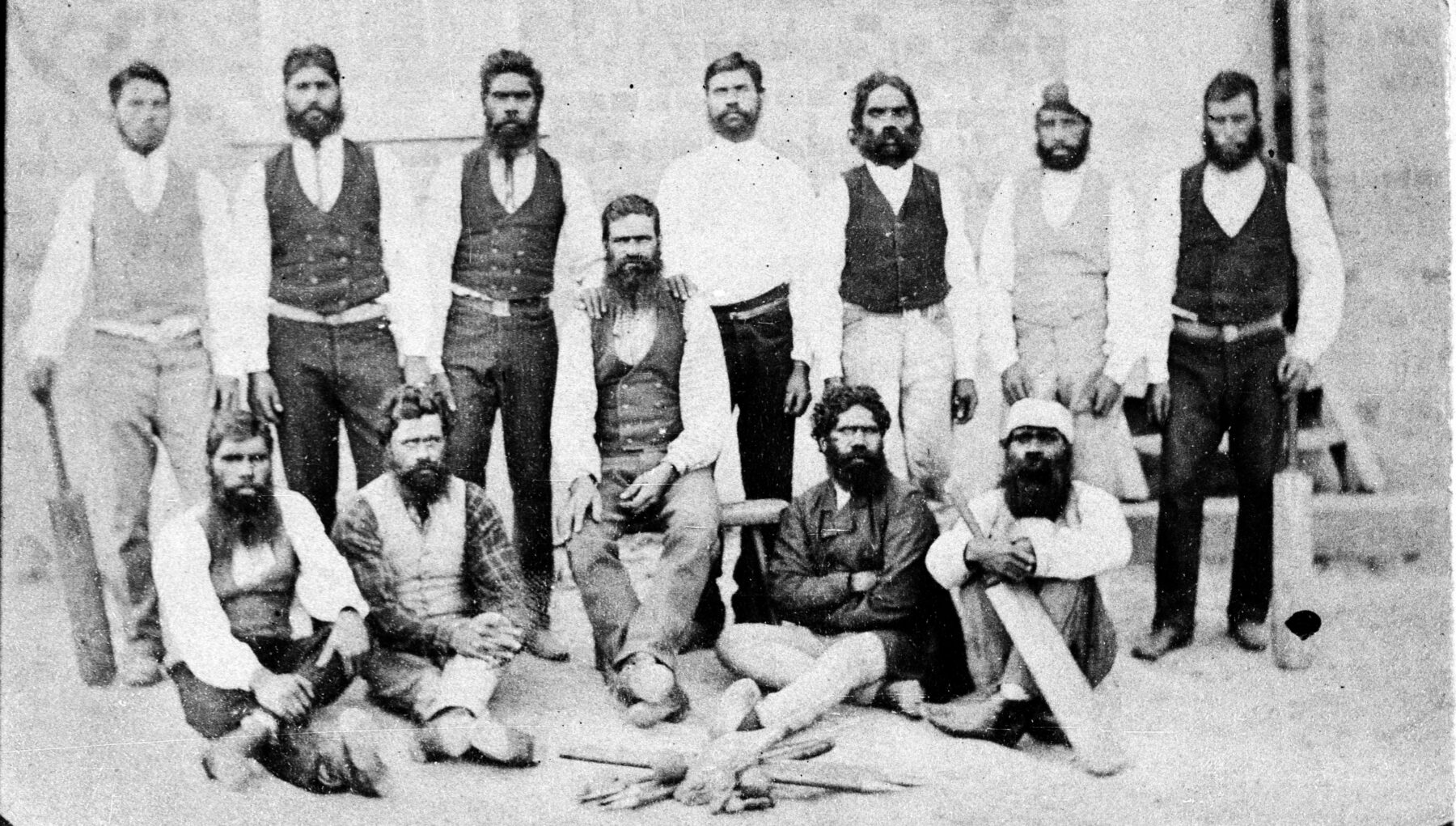

Six years later, in 1868, the first Australian team toured England, playing 47 games. The party comprised 13 Aboriginal players (mainly Jardwadjali, Gunditjmara and Wotjobaluk men), captained by Charles Lawrence. The tour attracted attention for both cricketing skill and entertainment such as boomerang throwing – one, it was reported, nearly sliced a stray dog at The Oval in south London. Unaarrimin (Johnny Mullagh) starred, with 245 wickets and nearly 1700 runs. Others, including Dick-a-Dick, Cuzens and Red Cap, are also fondly remembered.

Domestic popularity grew, but the appetite for international competition was paramount. In 1877 the first official Test was played at the MCG. Australia won by 45 runs – ironically, the same margin as the Centenary Test of 1977 that would be played at the same venue.

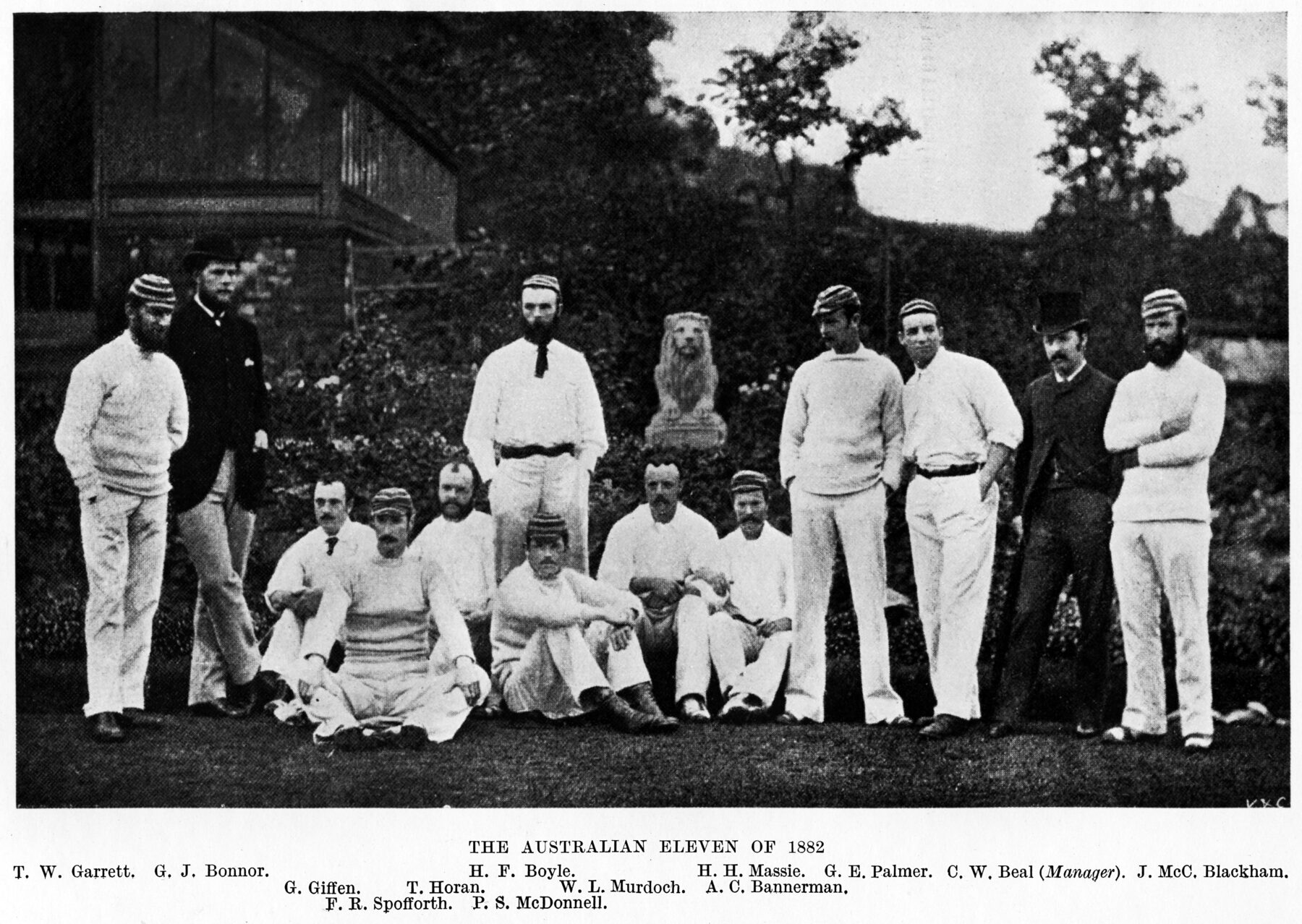

This marked the birth of Test cricket, though not of The Ashes. That came in August 1882 at The Oval.

A symbolic reward

Despite some excellent performances, including by the legendary Fred ‘The Demon’ Spofforth, Australia didn’t defeat an English side on home soil until that 1882 Test when the tourists won by just 7 runs. The shock among the English public at the loss was immense, and The Sporting Times printed a mock obituary for English cricket, concluding: “The body will be cremated, and the ashes taken to Australia.”

Before the next tour, English captain Ivo Bligh was given the task to “regain those ashes”, and so the iconic name for Test matches between Australia and England was born. During the 1882–83 series in Australia he was presented with a small ceramic urn by a group of women in Melbourne (including Florence Murphy, whom he later married). Legend says it contained a burnt bail, though some suggest it was a lady’s veil.

Whatever its contents, the urn became the symbol of the rivalry. England won that series 2–1 and Bligh kept the urn at his Kent home until his death in 1927. His widow presented it to the MCC, where it has remained ever since, apart from a brief tour to Australia in 1988. While the physical urn resides in London, the ‘ownership’ of The Ashes has shifted back and forth between the nations ever since. Australia has held them for approximately 86 years, England for 55.

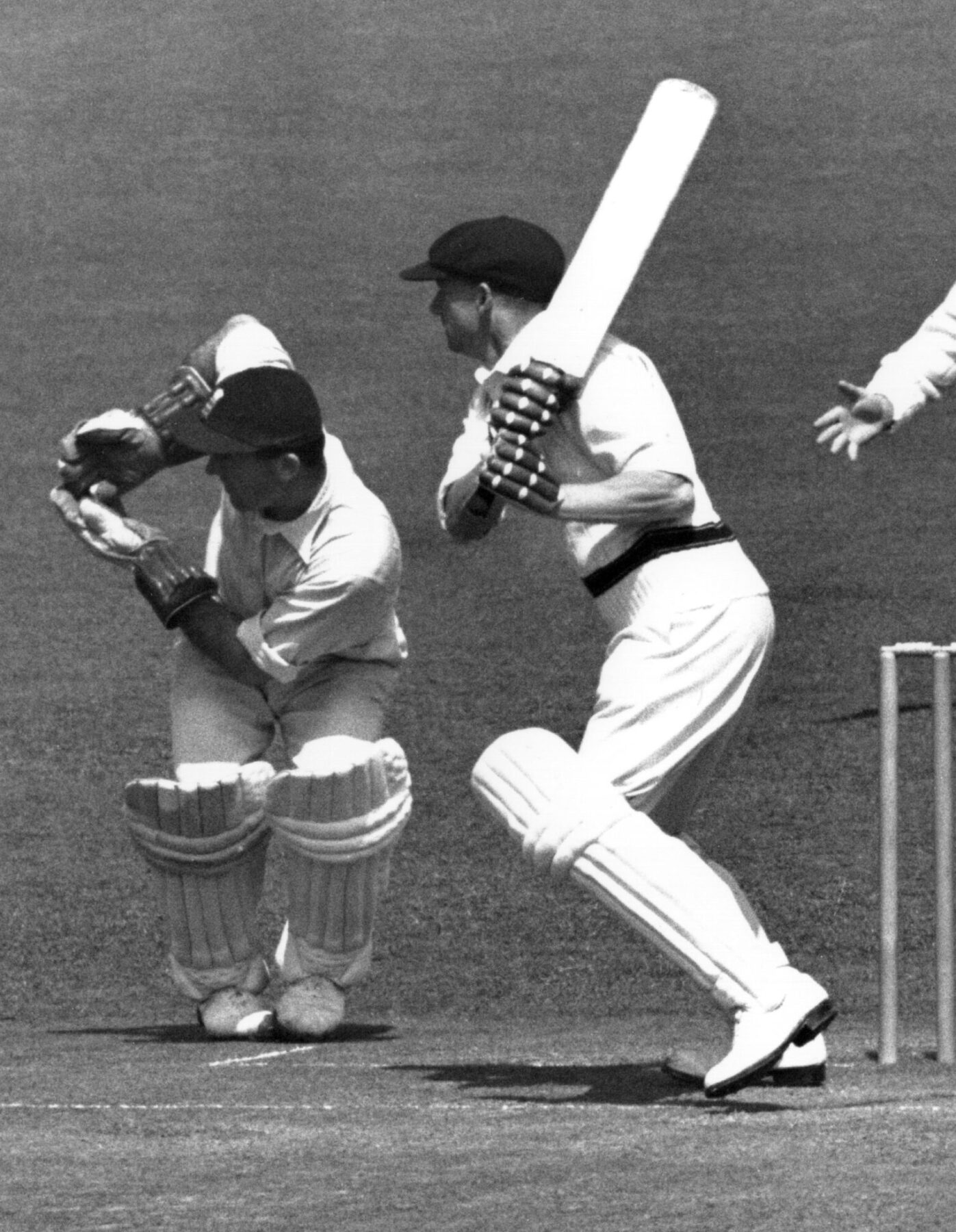

Beginnings aside, the legend of The Ashes owes much to Sir Donald Bradman and the infamous Bodyline series of 1932–33. Bradman, aka ‘The Don’ – already a national hero after scoring a record 974 runs in England in 1930 – faced England captain Douglas Jardine and fast bowlers Harold Larwood and Bill Voce in Australia. Jardine, aloof but shrewd, hatched a plan to reduce Bradman’s potency. It was called ‘leg theory’: relentless, short-pitched bowling at the body, backed by a packed leg-side field. It was within the laws, but seen as against the ‘spirit of cricket’ – a somewhat nebulous, unwritten code of fairness and respect that is still invoked regularly even today.

Tensions peaked in Adelaide when Larwood struck Australian captain Bill Woodfull and fractured wicketkeeper Bert Oldfield’s skull. Outrage spilled from the 50,000-strong crowd to the press, and even into diplomacy: Australia’s Board branded Bodyline “unsportsmanlike”, while London’s MCC rejected any criticism. A cricket contest had become a near diplomatic crisis.

Though Bradman’s average fell, he remained Australia’s talisman. Jardine was hailed at home but reviled here; Larwood, scapegoated by the MCC, never played for England again and later emigrated to Australia, where he was embraced.

Bodyline’s legacy endures: in law changes curbing leg theory and short-pitched bowling, and in the way every Test controversy since – from the infamous underarm bowling incident of 1981 to the ‘Sandpapergate’ ball-tampering scandal of 2018 – is measured against it.

In 1934, The Don paved the way for the Aussies to regain The Ashes in England. He became captain two years later during a home series in which he was again successful, but then oversaw a chastening series draw in England in 1938, before World War II intervened and Test cricket was paused for almost eight years.

Life after Bradman

Once the dust settled after the global conflict of 1939–45, Test cricket resumed. Australia won the return Ashes series in 1946–47. A year later, with the country still rebuilding, Bradman led perhaps the strongest Australian XI yet on a tour of England, including names like Arthur Morris, Sid Barnes, Keith Miller, Neil Harvey and Ray Lindwall. They played 34 matches, won 25, drew nine, lost none and became known as ‘The Invincibles’.

The only saving grace for the hosts was Bradman’s retirement, The Don leaving the game with an astonishing batting average of 99.94 (which famously became an answer in the Australian citizenship test). For context, the closest anyone has come to that average in almost 150 years of Test cricket is a handful of elite players who retired with an average just a shade over 60.

The inevitable break-up of The Invincibles impacted results. The Ashes changed hands in 1953, and only with Richie Benaud’s emergence in 1958 did Australia dominate again. Under Benaud they trounced England 4–0, won again in 1961, and also beat an emerging West Indies in a Test series that famously included the first-ever tied Test match at the Gabba in Brisbane – both sides finishing with 737 runs. Benaud stood down in 1964, replaced by Bobby Simpson and then Bill Lawry.

By this point, captaincy brought both fame and pressure. In 1971 Ian Chappell took charge, determined to bring back aggression and attacking cricket. Despite losing 2–0 at home in that tour that also featured the first One Day International (ODI) – not to mention a minor riot that led to England walking off the pitch – he began moulding a team in his own likeness. Dennis Lillee debuted, Rod Marsh took the gloves, and Ian’s brother Greg came to prominence.

The 1974–75 Ashes brought the true test. Chappell’s side was propelled by Lillee and newcomer Jeff Thomson – rapid, wayward and owner of a unique bowling action soon copied in backyards around the country. Lillee’s was the smoothest action around. Jason Gillespie, an Australian Test fast bowler from 1996–2006, recalls it fondly. “When I was a young child growing up, I just fell in love with watching the Australian team play and…basically watching Dennis Lillee run in and bowl,” Gillespie says. “He was an early hero. I became hooked almost immediately.”

England looked strong on paper but were no match for the raw pace of Lillee and Thomson. Australia romped to a 4–1 victory, their names indelibly etched into English minds. Thomson’s infamous line captured the mood: “I enjoy hitting a batsman more than getting him out. I like to see blood on the pitch.”

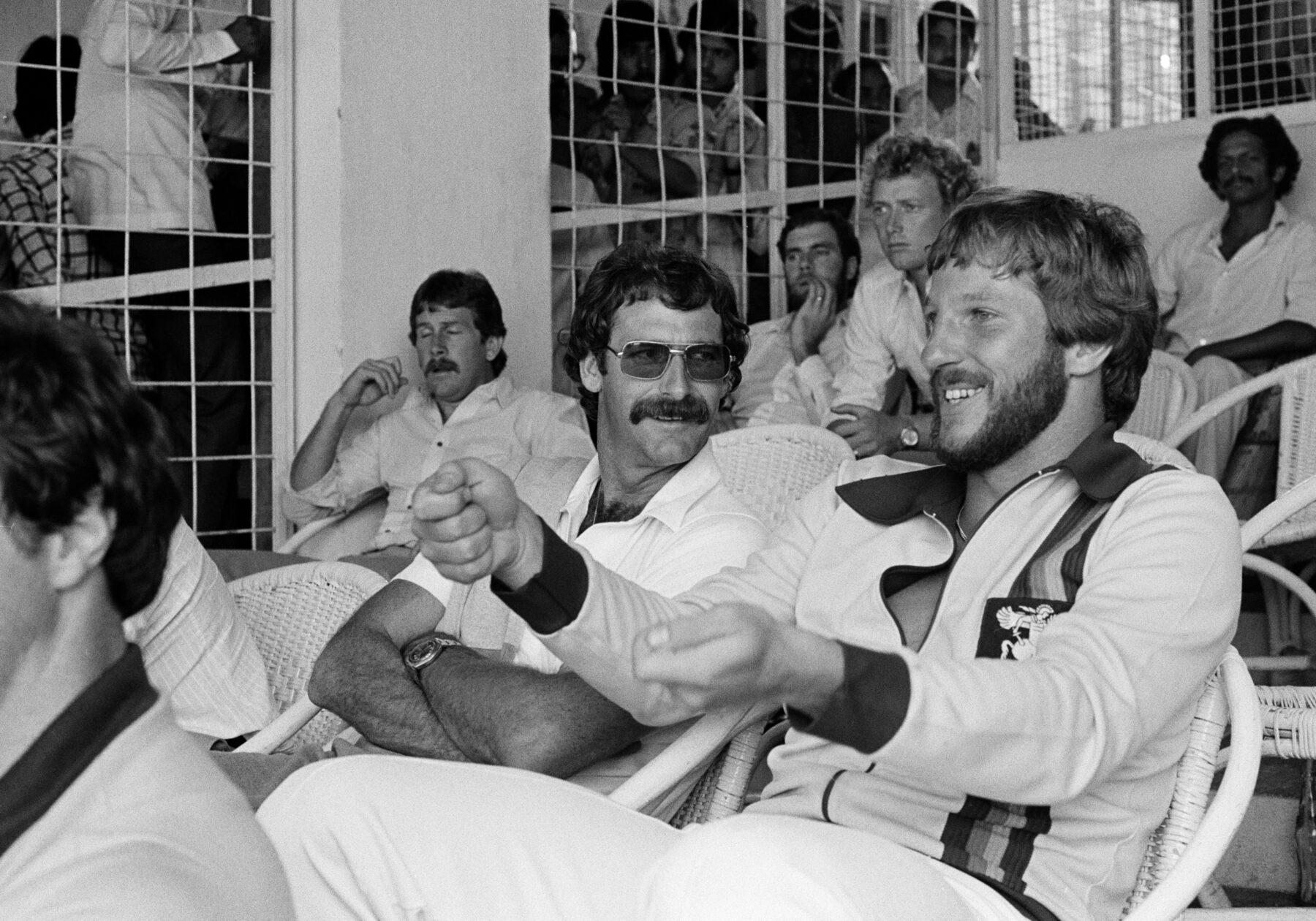

Together they took 58 wickets, leaving battered and bruised batsmen in their wake. Only Tony Greig stood up to the onslaught – and he would also soon play a key role in reshaping world cricket with Kerry Packer’s World Series.

New games

While Australia had climbed back to the pinnacle of Test cricket, the ODI version of the game was taking off. The first ODI was played at the MCG in 1971 between Australia and England after rain ruined the 3rd Test. A 40-over match was hastily arranged, Australia won, and though the press scoffed, the crowd loved it. By 1975, the one-day game was established enough for the first Men’s Cricket World Cup in England, while a Women’s Cricket World Cup had already taken place a couple of years earlier, in 1973.

As ODIs grew, TV rights became highly sought after. In 1976 the Australian Cricket Board rejected Kerry Packer’s bid, prompting him to launch World Series Cricket (WSC). Players such as Greig, the Chappells, Lillee and Marsh, as well as Clive Lloyd and Viv Richards (West Indies) and Imran Khan (Pakistan) signed up, creating a bitter split. Though derided as ‘Packer’s circus’ in some quarters, innovations like white balls, coloured clothing, day-night matches, stump mics, replays and better player pay revolutionised the sport. Without WSC, there might well be no Indian Premier League (IPL) or Big Bash League (BBL) today.

The rift ran from 1977–79 before a reluctant reconciliation, but it left Australia’s Ashes fortunes bruised. England, meanwhile, found a new talisman: Ian Botham. ‘Botham’s Ashes’ in 1981 remains one of the greatest cricketing summers, at least to English eyes. Meanwhile Australia, low on confidence and quality, were no match for the all-conquering West Indies throughout the 1980s, their blistering pacemen and powerful batsmen obliterating all before them.

Greg Chappell retired in 1984, Allan Border took over, and a shock 1987 World Cup win signalled the start of a turnaround. By the time Border retired in 1994 as Test cricket’s leading run-scorer, a new generation – Steve Waugh, David Boon, Dean Jones, Craig McDermott and Geoff Marsh – had emerged.

Mark ‘Tubby’ Taylor succeeded Border, routinely winning Ashes series and, in 1995, defeating the West Indies for the first time in eight Test series. Steve Waugh followed in 1999, his side ruthless and record-breaking with 16 consecutive Test wins. Glenn McGrath, Ricky Ponting, Adam Gilchrist, Matthew Hayden and Justin Langer all flourished under Waugh (and later Ponting). Yet, for all their collective brilliance, one unique cricketer cast a shadow that still looms largest: S.K. Warne.

From his debut Ashes ‘Ball of the Century’ delivery to Mike Gatting in 1993 to his final wicket (Andrew Flintoff) at the SCG in 2007, Shane Warne mesmerised opposition batsmen and cricket spectators the world over. He singlehandedly revived the dying art of leg spin, took a remarkable 708 Test wickets, was central to repeated Ashes triumphs, and won the World Cup in 1999 before retiring from the Test arena and becoming one of the most insightful thinkers and commentators in the game.

After retiring from Test cricket, Warne continued to ply his skills in the shorter form of the game, Twenty20 (T20). He led Rajasthan Royals to victory in the inaugural IPL (2008) and also later played for the Melbourne Stars in the BBL. As leading cricket writer Gideon Haigh explains: “Shane Warne is the hero of a thousand fights. There’s never been a better individual performance than his 2005 Ashes, not least because it was in a beaten side and in a period of very public personal turmoil. You dared not look away when Warnie was in action.”

Warnie’s numerous off-field indiscretions, and his ultimate premature demise, cannot tarnish the playing reputation of one of cricket’s all-time greats. For the English crowd at The Oval to collectively sing “we only wish you were English” to Warne in his final London Test appearance is testament to his talent and ability to dazzle and charm even the most cynical of crowds.

The rise of T20

If one-day cricket reshaped the sport in the 1970s, T20 took it even further in the 21st century. With its three-hour window, coloured spectacle and emphasis on power hitting, T20 was perfectly suited to modern broadcasting and new audiences. Where ODIs had once been the revolution, T20 became cricket’s entertainment product for a globalised, fast-paced era of increased competition for decreasing attention spans.

The Big Bash League launched in Australia in 2011–12 following on from its forerunner, the Twenty20 Big Bash, which had been a state-based competition. The change from the traditional state sides to franchise sides allowed for more local derbies in Melbourne and Sydney and also gave the game a chance to grow its target market – encouraging families and communities that perhaps hadn’t connected with the longer form of the game to embrace the new, faster, exciting and vivid version of cricket.

TV and live audiences responded positively, and overseas stars welcomed the chance to play with, and pit themselves against, the best of local talent. It also became a springboard for some players to push themselves into the thoughts of the national selectors across all formats, none more explosively than David Warner, who – as the first player since 1877 to be picked for Australia without a first-class match to his name – embodied how T20 was reshaping cricket’s pathways. The chance to see the next young fast bowler explode onto the scene was as compelling as watching old heroes and legends like Warne, and the West Indies’ Chris Gayle, demonstrate their prodigious skills.

Both Gillespie, who coached the Adelaide Strikers for nine seasons, and Sydney Thunder/NSW star Ollie Davies still see the benefits of spreading the reach of the game. “I had a wonderful time coaching in the Big Bash League,” Gillespie says. “It’s just a wonderful tournament, played at a really good time of the year. We get lots of families coming and watching. There’s pretty much a game on every day over that summer period. It’s a part of what summer’s about now.”

Davies’ experience as an up-and-coming player with a big future in the game demonstrates how exciting it is to actually make the transition from dreaming about playing to actually doing it. “I played for the Thunder against the Scorchers, one of the best teams to have ever played in the Big Bash. So, it was pretty daunting, making my debut. I remember, hitting Jason Behrendorff [an international player and one of the top wicket-takers in BBL history] for back-to-back sixes,” he says. “That was pretty surreal.”

traditional aesthetic. Image credits: Getty Images

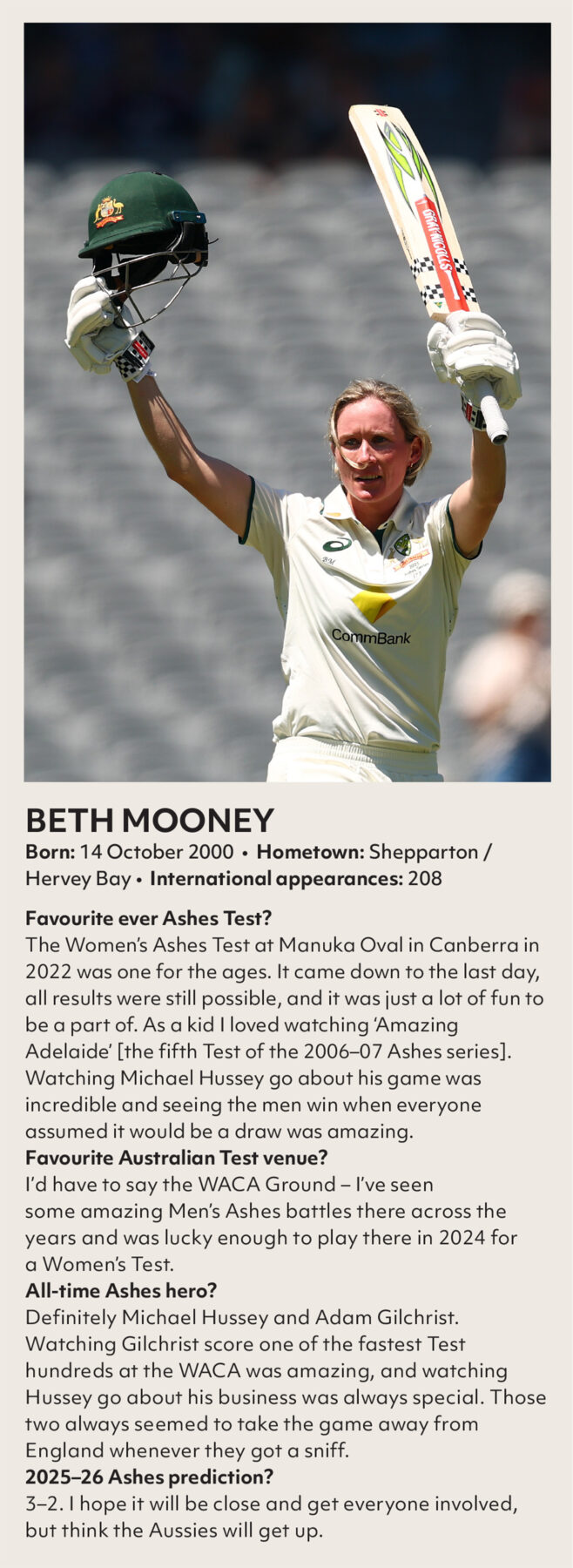

It isn’t just the men’s game that has benefited. If anything, the women’s game has flourished even more with the launch of the WBBL in 2015–16, initially as double-headers with BBL fixtures before it became a standalone competition in 2019. While the Australian women’s team has long been at the apex of the women’s game globally (with six ODI World Cup wins and a further six T20 World Cup trophies to their name), the chance for young families to see such great cricketing role models as Beth Mooney, Ellyse Perry and Alyssa Healy display their skills may well be the WBBL’s greatest legacy – inspiring a new generation of girls to believe that cricket is just as much their game as anyone’s.

No moment epitomised this growth like the night of 8 March 2020, the Women’s T20 World Cup Final at the MCG. There, in front of a record-breaking 86,174 spectators, Australia beat India by 85 runs, concluding with an iconic post-match concert by Katy Perry in which the victorious Aussies shared the stage. “When they said they wanted to get [almost] 90,000 people to the MCG for a World Cup final, I must admit I was a little bit sceptical,” said captain Meg Lanning after the game. Opening batter Healy added, “It’s a dream come true for me…cricket has done some really amazing things in this country for female athletes, and tonight was really just a celebration of that.”

Devoted fans

On the flip side, since the explosion of T20, Test cricket has struggled to retain its preeminent status. For every sell-out Boxing Day Test at the MCG, there are equally poorly attended games across a five-Test summer – particularly outside of The Ashes and, more recently, the Border–Gavaskar Trophy series (Australia vs. India).

In fact, a number of the other Test-playing nations are substantially reducing their commitment to the five-day game. South Africa, the reigning World Test Champions, aren’t playing a single home Test this summer. This is a concern for the purists. In addition, the lure of high-paying T20 franchises – particularly the incredibly lucrative IPL – that can attract young talent away from the extended version is something the custodians of the game (the ICC) have had to contend with.

Thankfully, The Ashes continues to bring with it an intensity and unique atmosphere that transcends shifts in formats and fashions thanks to its deep historical roots. Recent series in Australia have been firmly under Aussie control, but a resurgent England under the leadership of swashbuckling captain Ben Stokes and Kiwi coach Brendon McCullum are heading over with a spring in their step. McCullum defines the upcoming five games as “the series of our lifetime”. The England team has certainly revolutionised (and modified) their approach with their attacking ‘Bazball’ iteration of the game. Whether their gung-ho batting line-up is robust enough to withstand the remarkable Australian bowling attack remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, the home side faces a couple of selection questions, particularly at the top of the order. Gillespie reckons the left-handed opening bat Jake Weatherald has a good chance of forcing his way in. “He’s probably the closest thing in Australia that we’ve got to [the recently retired] David Warner from a left-hand aggressive, top-order type of player. He had a great year for Tasmania, averaging 50, scoring over 900 runs last summer. [He played] half his games at Bellerive Oval in Hobart, which is very much a bowler-friendly surface.”

If Weatherald is selected or not remains to be seen, but Gillespie’s reflections echo an age-old Ashes ritual: musings and predictions about who might next join cricketing folklore. That uncertainty is part of the magic – from Bradman to Botham to Warne, each series writes a fresh chapter in a story that began in 1882.

As has also become ritual, England will be roared on in the 2025–26 series by their travelling ‘Barmy Army’ who have provided a regular soundtrack to England Test matches since the 1994–95 tour to Australia. Despite some rather abject displays on the pitch, the Barmy Army never let a bad performance get in the way of a good time.

Australian supporters responded in due course with the ‘Fanatics’, who were initially formed to follow Australia in tennis’s Davis Cup in 1997 and subsequently appeared at Australian cricket fixtures in the early 2000s. They were then joined in 2011 by ‘The Richies’, who dress uniformly in cream jackets, shirts and ties, with silver wigs and compulsory microphones, in honour of the much-loved and now sadly departed Richie Benaud, who after captaining his country in the 1950s went on to become the voice of cricket for generations as a commentator.

The combination of those three supporter groups alongside regular Test cricket aficionados pretty much guarantees full houses across the traditional Ashes venues. But which group creates the best atmosphere? “I’m gonna say the Barmy Army,” Gillespie says. “I’d love to say the Fanatics, but the Barmy Army are on a different level. Even though I’m an Aussie, I think they’re wonderful for the game of cricket. They make an Ashes summer. Even if they give us Aussies some stick and get stuck into us a bit, they get behind the English cricket team. I think it’s brilliant for the game. It’s part of the tapestry.”

Supporters help set the tone, but what truly sustains The Ashes is its tradition and meaning. Haigh explains why: “The Ashes doesn’t always produce the best cricket – sometimes it’s downright uninspiring,” he says. “But when it’s good, it pops, because it slots into such a pantheon of greats and ancient inheritance. In a time when there’s an anxiety about causing offence, it also allows for pretty free expression. I like that line from Sir Robert Menzies about the two countries knowing each other so well that they don’t have to be too polite to each other. Part of its durability is the fixedness of the five-Test duration. It hasn’t compromised. It hasn’t obviously commodified. It still lays claim to what it’s always had, and that confidence about itself is infectious.”

Park life

Despite what we see at the pinnacle of the sport, cricket begins – and mostly exists – in the backyard or local park, as kids around the country replay their favourite strokes, deliveries, catches or run-outs. While he now represents NSW, Sydney Thunder and Australia A, Davies started out the same way.

“We played Kanga Cricket – myself, Joel [Ollie’s younger brother and now a Sydney Sixers regular] and Lucy [their sister]. We played just down the road from ours at Adams Street, and our dad, Kev, would always go down on a Friday afternoon and mow out a little pitch so that we’d have our own little wicket to play on,” Davies says.

“There were a few times people would rock up before us and try and take the pitch that Dad had made. So, Dad would have to kick them off. That was one of my earliest cricket memories. It was quite funny, but it was also very wholesome. Just Lucy, me and Joel playing cricket together.”

Davies also fondly recalls junior mornings with the Harbord Devils: “Every Saturday morning, looking forward to getting up out of bed and heading to Harbord Park to play. I always have flashbacks of memories playing there every time I drive past it, which is most days.”

Gillespie shares the same affection for his beginnings: “Adelaide Cricket Club,” he says. “I always enjoyed that. We’ve got a lot of lovely, picturesque cricket grounds in South Australia…all over the country there’s beautiful cricket clubs and grounds.”

Perhaps surprisingly given the exploits of Unaarrimin/ Johnny Mullagh and his team-mates on the Indigenous tour of 1868, Gillespie was recognised as the first Indigenous Australian to play men’s Test cricket when he debuted in 1996. Only four Indigenous Australians – Faith Thomas, Ashleigh Gardner and Scott Boland are the others – have played in Test matches. Gillespie takes a keen interest in the continued development of the game in First Nations communities. “My son played in, and I came up and watched and commentated on, the Australian Indigenous Championships. It was good to see all the Indigenous players showcasing their skills,” he says. “Much needs to be done to continue to promote Indigenous cricket to the wider community and to engage more Indigenous players to get involved in the game. We want to get more Indigenous kids falling in love with the game of cricket.

“There’s so much more that can be done. Cricket Australia have said they’re keen to do more, so I’m really looking forward to seeing them follow through on that promise.”

From tentative beginnings in Hyde Park over two centuries ago to the full-blown razzamatazz of today’s BBL, cricket continues to engage, to bring joy, to bond us. It’s the game that gave us Spofforth, Bradman, Benaud, Lillee and Thomson, Border and Waugh, McGrath and Warne – names woven into the nation’s story. It has courted controversy, produced heroes and villains, and fuelled debates that spill far beyond the boundary.

Above all, cricket has been a thread of connection. Whether it’s in the backyard or at the MCG; on the beach or in a forecourt during a lunch break with a wheelie bin as a wicket; cutting a turf wicket down at Adams Street; listening to another England collapse at the Gabba on the car radio while waiting for the bloke from NRMA to turn up; or coercing an ageing body to bowl a tennis ball at your grandson, just like Thommo, one last time – cricket creates those shared “I was there” moments that lodge in the memory. The game is part of the nation’s DNA.