The year 1975 was memorable for the people of Australia for many reasons. It kicked off with the tragic Tasman Bridge disaster. In April the Vietnam War, which claimed the lives of 523 Australians, came to an abrupt end. In September Papua New Guinea gained independence. And two months later, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam gave his famous “nothing will save the Governor-General” quote after his dismissal. It was a year when Australian television switched to full-time colour broadcasting. The Don Lane Show made its debut, and The Bee Gees had a hit with “‘Jive Talkin’”.

But what of the film industry?

Jaws – the world’s first blockbuster film – was released in 1975, terrifying ocean-going audiences across the globe. Hollywood films had been showing in Australian cinemas for decades, but 1975 was when local movies became hits on the silver screen. Two standouts include The Man from Hong Kong and Picnic at Hanging Rock. These two films were far apart in style and pace, yet had more in common than many would believe – notably in the showcasing of some famous Australian rocks.

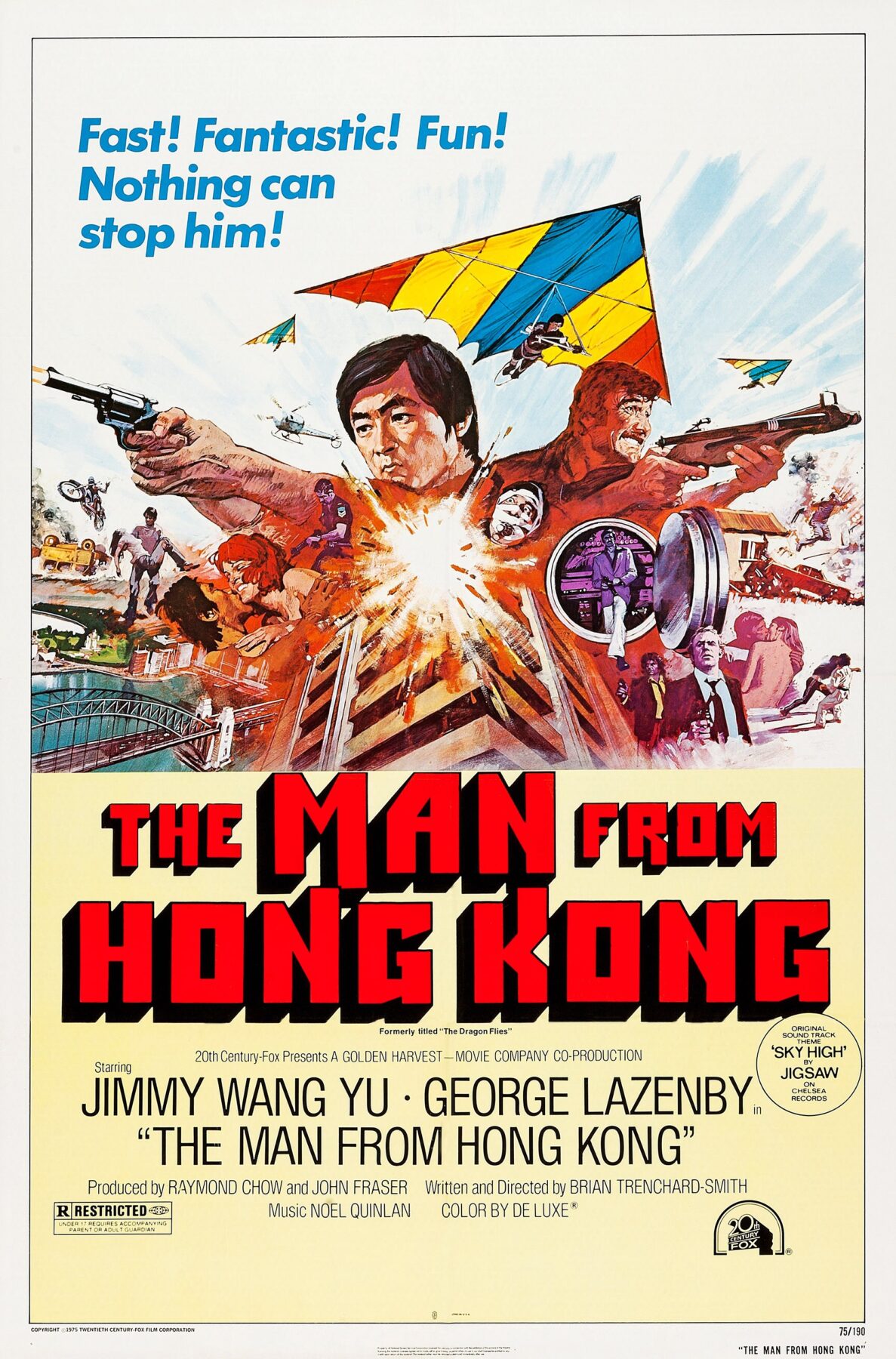

The Man from Hong Kong was the first Australia–Hong Kong co-production and the first Australian martial-arts movie. The action-packed adventure, filmed at the height of 1970s kung-fu mania, focused on a Hong Kong Dirty Harry-style cop who rips up Sydney to bring down a powerful drug lord.

The film’s director, Brian Trenchard-Smith – who worked his way up as a television editor before getting his big break – described this picture as “a veritable smorgasbord of martial-arts mayhem, James Bond spoofery and general thud and blunder”.

It was initially set to be a Bruce Lee vehicle, but after his untimely death in 1974 he was replaced by Hong Kong’s new top star, Jimmy Wang Yu, dubbed the ‘Steve McQueen of Asia’. George Lazenby, Australia’s 007 star, was cast as the heavy.

The co-production was also notable for featuring three of Australia’s most famous landmarks: the Sydney Opera House, Harbour Bridge and Uluru (then known as Ayers Rock). Of the three landmarks, ‘the rock’ in Central Australia would be the most challenging and most questionable. “Why not here? Why not on top of Ayers Rock?” Trenchard-Smith asked. The director said that having an action-packed opening of an improbable drug deal in an unlikely place was a good way to subvert action-movie tropes at the time – a ploy Alfred Hitchcock used in his 1959 spy thriller North by Northwest bysetting the climax on top of Mount Rushmore.

Filming at Uluru was by no means a novelty; it had previously featured in the 1967 picture Journey Out of Darkness. But nothing in that production compared to the antics that were to happen on this action vehicle.

A precarious location

Principal photography began and wrapped on the rock in late 1974, followed by a December shoot in Hong Kong. It had rained heavily before the crew arrived at the site. As a result, Trenchard-Smith found the location filled with deep greens on and around Uluru, which was unusual for that area.

With three days to film, he wasted no time. Scouting the star location, he climbed up and down the steep formation three times in one day, grateful for the chain handhold in place then. Installed in 1964 to assist hikers making the one-hour climb to the top, the handhold certainly benefited the film crew.

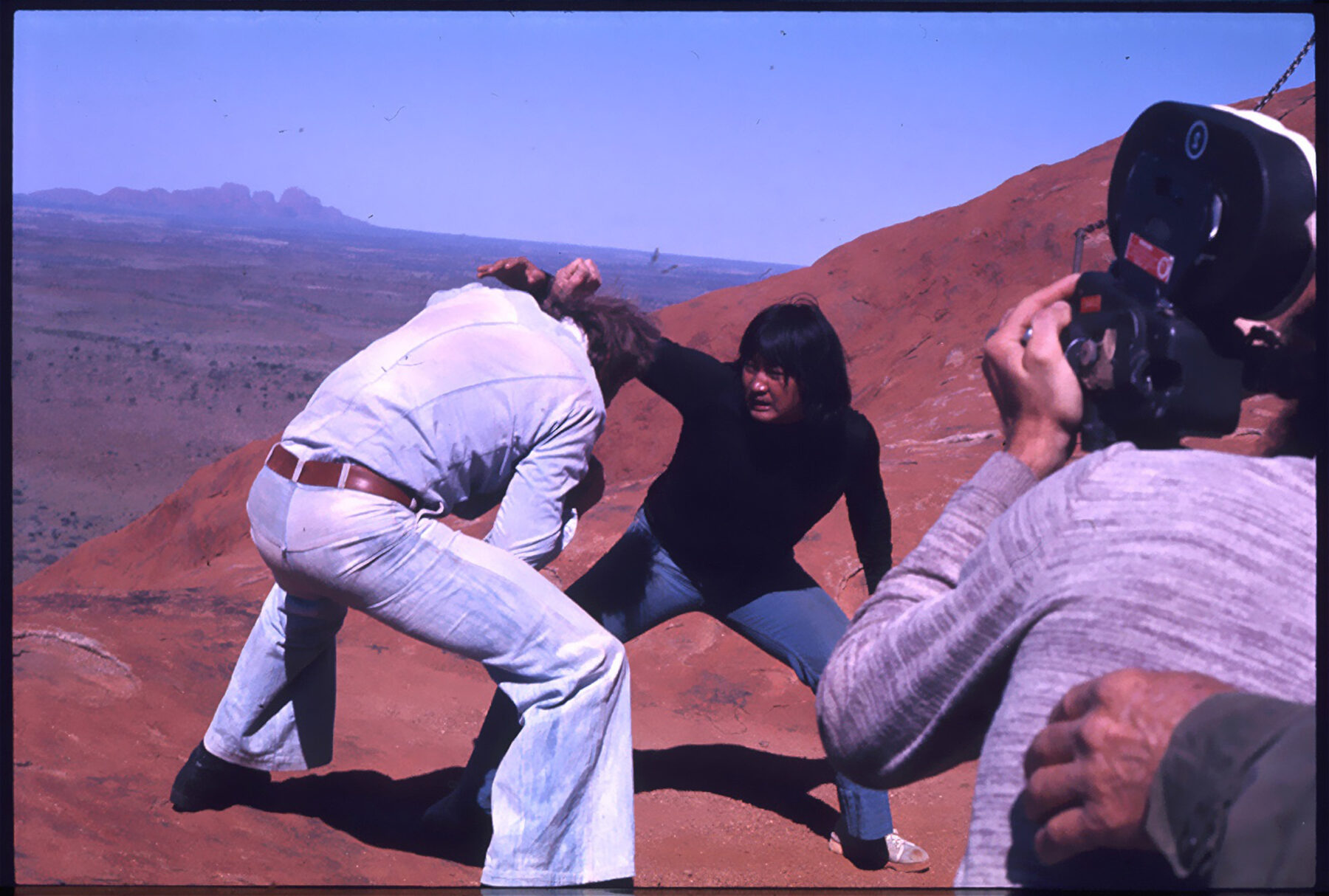

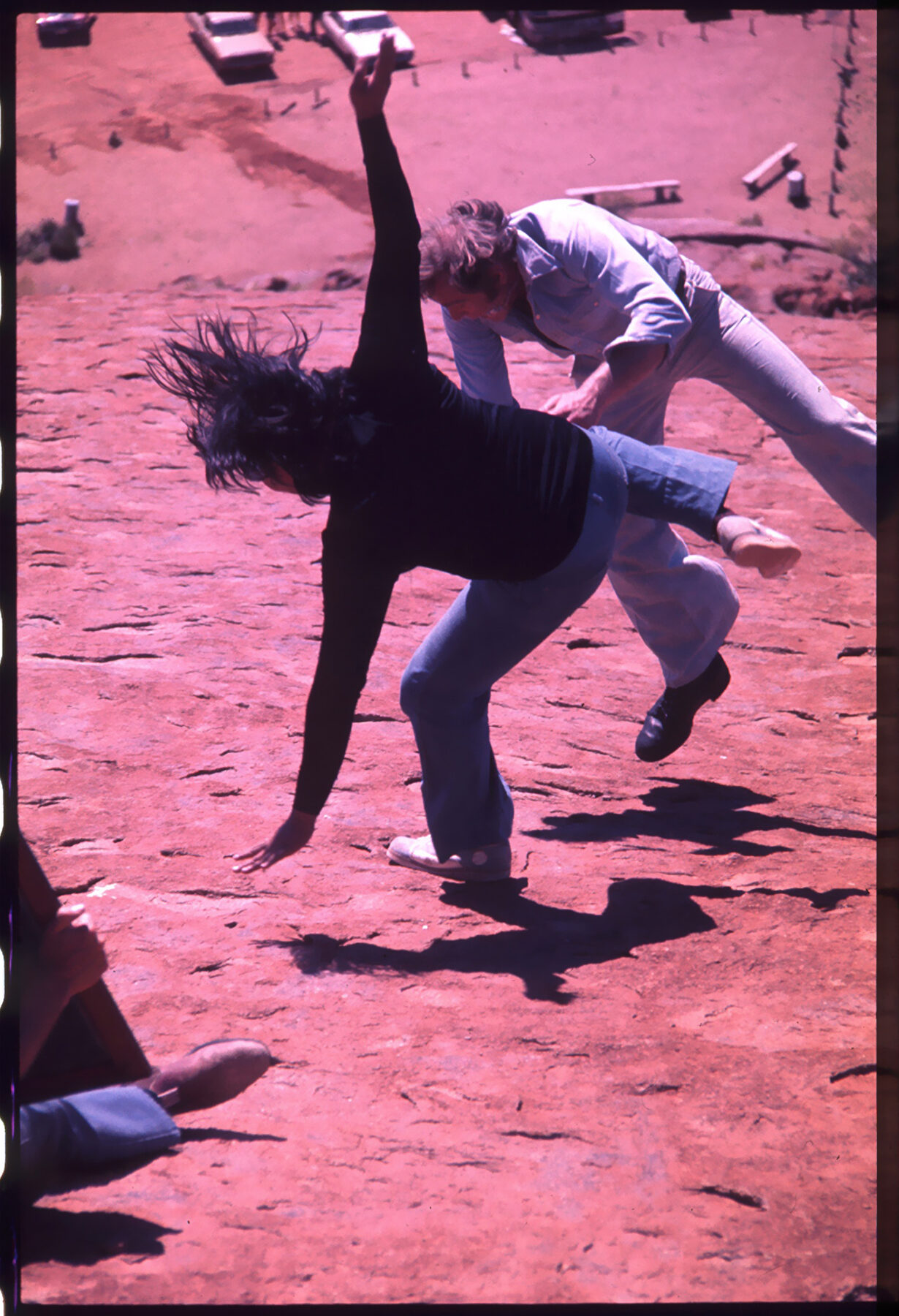

The film’s opening action scene on the rock featured an intricate kung-fu brawl, without protective padding, between actors Sammo Hung and Roger Ward on a slightly perpendicular slope – a spot where many unfortunate tourists had fallen to their deaths. Adding to this outrageous scenario was one amusing incident involving some Japanese tourists who caught one of the performers baring it all at the national landmark. Considering the current protection of Uluru, it’s hard today to fathom any of this happening.

With the fight scene wrapped, it was time to film the next big action set piece in front of the rock, which involved a fleeing car, pursuing helicopter and vehicle explosion. Despite taking precautions, the flying door from the exploding car missed the crew by only metres – prompting the director to say, “Whoa! That thing’s getting awful close!” The mishap was captured on camera and made the film’s final cut.

By the time the three-day shoot was over, many of the cast and crew were suffering from heat exhaustion and given a well-deserved rest.

If 1971 was year zero… then 1975 was the year Australian cinema took off, breaking foreign barriers.

When production returned from Hong Kong it finished with a literal bang in January 1975 with an explosion at the (former) Esso building in Sydney. With no time to break, director of photography (DOP) Russell Boyd and camera operator John Seale – two future Academy Award-winning cinematographers – began preparing for their next movie assignment, Picnic at Hanging Rock, for which production would begin the following month.

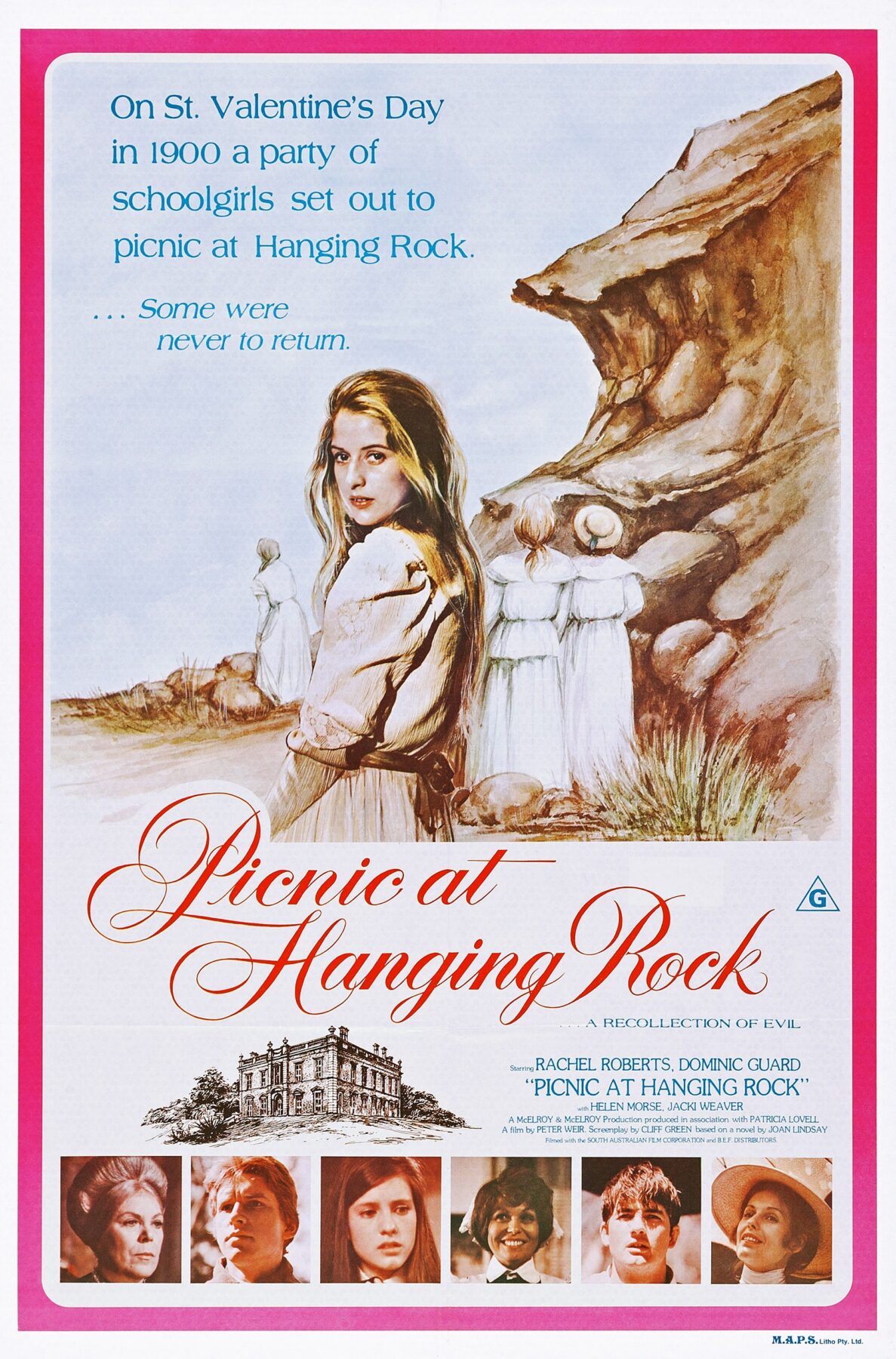

Based on Joan Lindsay’s 1967 gothic mystery novel of the same name, Picnic at Hanging Rock was to be filmed at the picturesque Hanging Rock Reserve in Newham, Victoria. The story focused on the strange and unexplained disappearance of schoolgirls and a teacher on Valentine’s Day in 1900 while visiting the site.

This was the second cinematic adaptation of this novel, following the 1969 short Picnic at Hanging Rock: The Day of Saint Valentine, which was unfinished. Part of the story’s appeal was that many moviegoers were convinced it was a true event, not based on a work of fiction.

Directing the 1975 film was a young Peter Weir, whose previous vehicle had been the 1974 The Cars That Ate Paris, a dark horror comedy that became one the first Australian pictures to screen at the Cannes Film Festival. It was eventually shown in America where it did poorly at the box office, as it did in Australia. Despite this, it was not the last time Weir attempted to hit the international market, as he was about to embark on his most ambitious project yet with Picnic at Hanging Rock. He teamed up again with producer twins Jim and Hal McElroy – the latter had previously worked on The Man from Hong Kong as an assistant director, and both had produced The Cars That Ate Paris.

The six-week shoot began in early February 1975, filming in South Australia and at the Hanging Rock Reserve in Victoria. The production featured a mostly young cast of newcomers and marked one of the first major dramatic roles for Aussie actors Jacki Weaver and John Jarratt.

As for the look of the film, Weir wanted to give it an appearance of an impressionist painting. Cinematographer Boyd achieved this by placing bridal veils over the camera lens, creating dreamy visual effects. This made the Hanging Rock Reserve appear more sinister, adding to its mystique.

Shooting the picnic scene had its challenges. Boyd had only a one-hour window each day to film with perfect light cast on Hanging Rock, from noon to 1pm. Filming went smoothly at the star location with the exception of a couple of strange occurrences recalled by the cast and crew: equipment going missing, watches stopping mysteriously (just like they did in the film), and a bizarre rainstorm.

With a promotional trailer cut by Trenchard-Smith, Picnic at Hanging Rock premiered in Adelaide on 8 August 1975, exposing audiences to the opening master shot of the menacing-looking Hanging Rock.

The film was a huge critical and financial hit in Australia and overseas, getting much praise in the US when released there in 1979. This picture, along with Sunday Too Far Away – another hit Aussie film released in 1975 – helped usher in the ‘Australian New Wave’, which included movies such as My Brilliant Career (1979)and Breaker Morant (1980). Weir and Boyd would make another five pictures together, culminating in Boyd’s Best Cinematography Oscar win for Weir’s 2003 masterpiece Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World.

What of Trenchard-Smith’s The Man from Hong Kong? It sold within days to every available territory and became a hit at the 1975 Cannes Film Festival. The director was later offered various US film deals. Premiering in five cities across Australia on 5 September 1975 – a month after Picnic at Hanging Rock – audiences were rocked by Uluru’s picturesque scenery, captured by Boyd, and the mayhem of the opening scene.

Despite receiving great international recognition, The Man from Hong Kong didn’t garner the same success locally as Picnic at Hanging Rock, but was the key so-called ‘Ozploitation’ movie – exemplified by Mad Max (1979) and Roadgames (1981) – to take that genre to the next level.

Today Trenchard-Smith’s wider body of work has a huge cult following, and even Quentin Tarantino lists him as one of his favourite directors. If 1971 was year zero for the commencement of Australian cinema – with pictures such as Wake in Fright – then 1975 was the year Australian cinema took off, breaking foreign barriers with the help of these two films ‘on the rocks’.

And what about the films’ unofficial stars? Uluru continued to get the spotlight in the 1988 movies A Cry in the Dark and Young Einstein, but would never host another fight scene atop it. Considered a sacred site, it closed to climbers on 26 October 2019, and the handheld chain showcased in the kung-fu brawl in The Man from Hong Kong was removed. As for Hanging Rock Reserve, its popularity increased after the 1975 film, which also inspired a 2018 mini-series remake that was shot at the same location. To this day the location is still marketed as an area of mystery.

Even if you never get to see these two rocks in person, you can still marvel at them in two groundbreaking films that lit up the big screen 50 years ago.