Australian astronomy at a crossroads

Fred Watson

Fred Watson

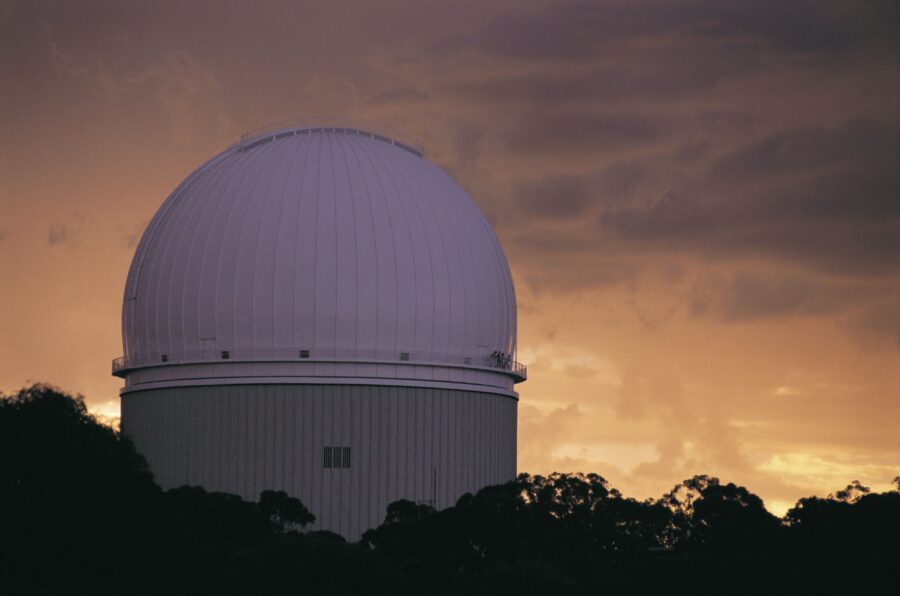

Funded jointly by the two governments, the telescope’s 3.9m-diameter mirror placed it among the world’s largest optical (visible light) telescopes. It was the perfect complement to Australia’s growing radio astronomy capabilities.

I have recounted already the telescope’s illustrious career – but while it’s still producing world-class data, it no longer ranks among the world’s biggest. And in astronomy, size is everything – closely followed by location. Today, that ideal location is the mountain tops of northern Chile, where exquisite atmospheric conditions have spawned a new generation of large optical telescopes.

Thanks to Australian Government investment in 2017, our astronomers have had access to the most capable of those telescopes as part of a 10-year strategic partnership with the European Southern Observatory (ESO), which operates four 8.2m-diameter telescopes on behalf of 16 European countries.

That arrangement spectacularly energised Australian optical astronomy, but it’s now approaching its end – and the pathway to what follows is currently unclear. The logical next step is full membership of ESO, which both ESO and the Australian astronomical community seek eagerly. The drawback is that the investment is sizeable, albeit consistent with the costs of most cutting-edge science infrastructure.

Meanwhile, another potential game changer is taking shape on one of those Chilean mountain tops, where a 6100-tonne rotating dome towers 80m above the barren landscape of the Atacama Desert. Under construction inside is ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), which will be by far the world’s largest when completed in 2029. The ELT will have a dished mirror that’s 39.3m in diameter. It’ll be nearly 300 times more sensitive than the Hubble Space Telescope, and will reveal detail on a scale 20 times finer.

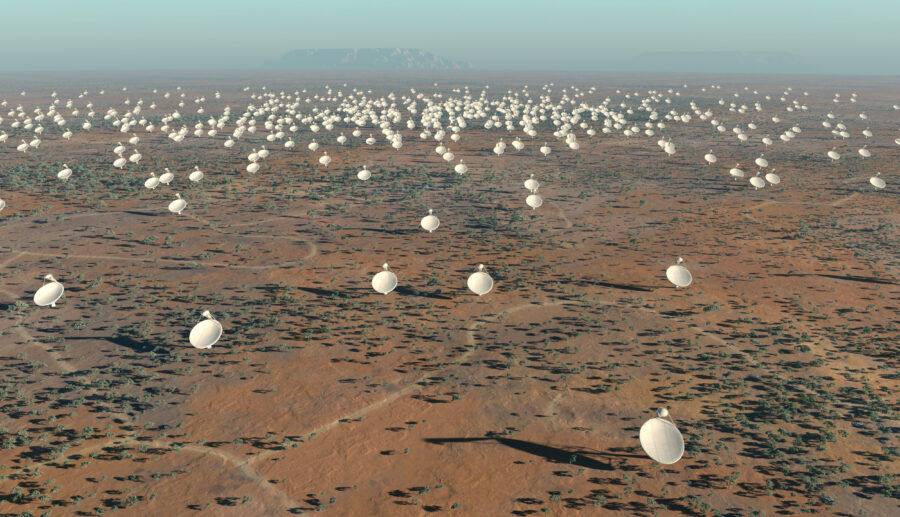

This instrument will revolutionise science, leading to Nobel Prizes. And if full ESO membership is secured, Australian astronomers could find themselves in pole position. That’s because the ELT perfectly complements what will be the world’s largest radio telescope: the international Square Kilometre Array Observatory, the low-frequency component of which is under construction on Wajarri Country in Western Australia, about 630km north of Perth. (Its high-frequency counterpart is being built in South Africa.)

Together, these instruments will herald a generational advance in research – from questions about the universe’s infancy to the quest for extraterrestrial life. With such extraordinary potential for our international standing in astronomy, the cost of ESO membership seems like a bargain.