Digging for dinosaurs in the Gobi Desert

John Pickrell

John Pickrell

This is an account of the 2015 AGS Gobi expedition. Want to participate in 2016?

DAY HAD TURNED to night, despite the sun being high in the sky, and I braced myself against winds, the like of which I had never experienced before. One of the Gobi Desert’s legendary sandstorms had arrived, disturbing the day’s fossil-hunting activities.

Sheets of sand and dust pounded against us as we packed up our gear and retreated to our parked convoy of 4WDs. Such dust storms are not altogether surprising in the Gobi, and we were well prepared. I was covered up with long sleeves, a beanie and cargo pants, and my eyes were protected by both wrap-around sunnies and a pair of goggles. A bandanna tied across my nose and mouth helped keep the dust out.

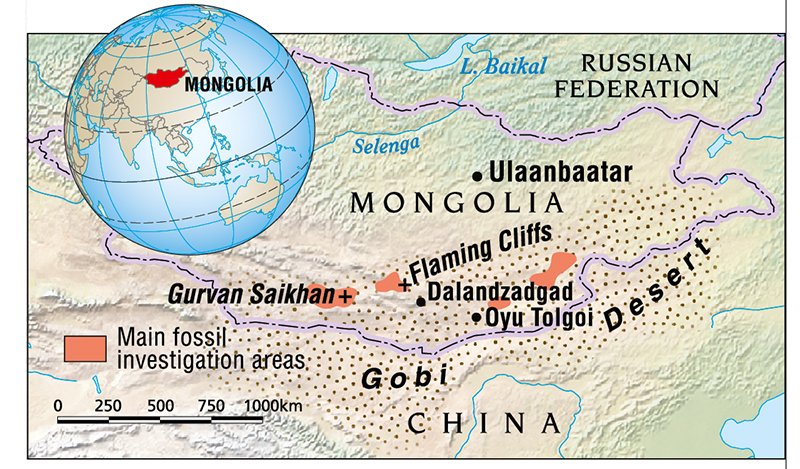

The Gobi Desert is a starkly beautiful region, rich in mysteries and legends. Covering 1.3 million square kilometres of southern Mongolia and the Chinese province of Inner Mongolia, it stretches south from the Siberian wilderness to the Tibetan Plateau.

Conditions are not always ideal, but the thrilling experience of a sandstorm only added to the excitement of this adventure for me and a small and enthusiastic crew of Australian volunteers.

We were there to prospect for and collect dinosaurs for the Mongolian Academy of Sciences (MAS) on a fossil-dig expedition that was a collaboration between the academy, Odyssey Travel and the Australian Geographic Society.

This April 2015 dig was on a small scale – with just a handful of paying participants – and was a recce for a much larger expedition, which will take place in September 2016 with 15 AG readers. I led the dig along with Dr Tsogtbaatar Khishigjav, renowned dinosaur hunter and head of the MAS’s Institute of Paleontology and Geology in Ulaanbaatar.

The whole trip lasted 17 days, with eight days -camping hundreds of kilometres from anywhere in the eastern Gobi. The rest of the time was spent in the capital Ulaanbaatar and visiting a series of significant fossil and geological sites, as well as the spectacular Gurvan Saikhan (‘three beauties’) mountains.

Palaeontology assistant and student Mainbayar Buuvei excavates a dinosaur fossil (Credit: John Pickrell)

Mongolia – a country of contrasts

Mongolia is a country of contrasts; 800,000 of the 1.3 million inhabitants of the capital still live in traditional circular ‘tents’ in the city’s sprawling ger district. Easy to pack away and transport, these gers or yurts have been the favoured dwellings of Central Asian nomads for millennia – but today they seem at odds with Ulaanbaatar’s glitzy new skyscrapers and shopping malls, filled with luxury goods, shops and fine restaurants with wide selections of European wines.

Since the fall of communism in the 1990s, mining has brought new wealth and rapid urbanisation to a country of only 3 million people, 45 per cent of whom are found in Ulaanbaatar, the only sizeable city. Much of the rest of the population still lives a traditional nomadic lifestyle, tending sheep and camels across the steppe and desert that covers the majority of Mongolia.

Oyu Tolgoi, a massive copper and gold mine in the south Gobi near the border with China (owned in large part by a subsidiary of British-Australian multinational Rio Tinto), is a great example of the wealth pouring in. It is claimed that this mine – supported by the new airport into which we flew from Ulaanbaatar – will account for 30 per cent of Mongolia’s entire GDP when running at full capacity in 2021.

We had begun our adventure with several days in Ulaanbaatar. There we visited the Gandan Monastery, some museums and a shopping mall housing the incredible MAS dinosaur collection while the natural history museum is being renovated. We also spent time in the fossil preparatory lab of the Institute of Paleontology and Geology, stacked with specimens that technicians were slowly chipping out of great slabs of rock and sand.

Palaeontologists and volunteers at our camp in the eastern Gobi (Credit: John Pickrell)

Exciting dinosaur fossil find

ONE OF THE most exciting moments of the trip for me was the discovery of the partial jawbone of an Alectrosaurus. This rare, 6m-long carnivore was related to T. rex and lived in Mongolia about 80 million years ago, during the Late Cretaceous.

A small piece of unusual reddish stone with pits along it had caught my attention and 30 minutes of carefully brushing sand away had revealed the front-left part of a lower jaw, which still had a single tooth attached to it. The pits I’d spotted were where nerves once attached to each tooth.

Alectrosaurus was first discovered in the Chinese part of the Gobi in 1923, and though teeth are common here, skeletal remains such as this had not been found in Mongolia since the 1970s. We spent much of the rest of that afternoon digging out a pedestal of dirt around this important specimen and then wrapping it in hessian and plaster for its return to Ulaanbaatar.

“There was a hope and expectation that I’d personally uncover something of interest. I was not disappointed,” says Clint Coker, 57, a pharmacist from Noosa Heads, Queensland, who had no prior experience of digging or palaeontology, and whose top find was a series of dinosaur footprints.

“Every day prospecting was like being a kid on a treasure hunt… Investigating every possible find, carefully brushing away the soil and exposing dinosaur remains, knowing that you were the first person to see them and that they were laid down 80 million years previously.”

Alhough Tsogtbaatar was accompanied by some palaeontology students and assistants, we were unable to collect larger specimens we found, such as the articulated legs of a duck-billed hadrosaur.

We reburied these to hide them from fossil poachers – an ever-present threat in the Gobi (fossils are often hurriedly extracted and smashed, with flashier parts, such as skulls and claws, sent overseas to feed the black market for Mongolian fossils).

Thwarting the fossil poachers

But small and important specimens, such as pieces of rarer carnivorous dinosaurs and anything not well represented in the academy’s collections, were carefully encased in plaster and collected.

Each year the winds and sandstorms scour off the surface rocks, exposing a new layer of fossils. This means there are constantly new things to find, but also anything left on the surface is likely to have disintegrated and blown away by the following summer.

All of us Australians on the dig were astounded at the fossils we left behind in the Gobi. At some of the sites we were literally tripping over pieces of herbivorous hadrosaurs – the kind of fossils experts can only dream of finding in Australia, where any small piece of dinosaur is a hard-won treasure. Here, Tsogtbaatar tells us, they already have large numbers of excellent specimens of these species and have no need of more in their collections.

Robbin Waterhouse, a retired doctor from Townsville, Queensland, said his interest in joining the dig was a long-held desire to see the Gobi and an excuse to wander in the wilderness. “The most surprising aspect of the trip for me was the ease of finding specimens, not to mention that we discarded anything that wasn’t rare or in first-class condition,” he says. “But a close second was having Dr Tsogtbaatar with us as resident expert.”

Doug Miller, 61, a retiree from Brisbane who frequently volunteers at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum in Winton, Queensland, says that for several decades he’d wanted to visit Ulaanbataar and find a way to get on a fossil dig in the Gobi.

“The opportunity to work with distinguished and dedicated palaeontologists like Dr Tsogtbaatar and his assistant Mainbayar was an unexpected bonus and added great credibility to the dig. The ease with which we found fossils was a surprise…and we had a couple of infamous Gobi dust storms to boot.”

Responses to the experience from all the volunteers in our small group were varied but all enthusiastic. Robbin’s partner Margaret Thacker, 73, a retiree who volunteers at the Museum of Tropical Queensland, says she had few preconceptions, but “the dig and people associated with it were far above my expectations. Especially the companionship and the way we all worked so well together, and that we were able to cope with the sandstorm and the tents blowing down with a sense of humour.”

The Gobi has a population density of just 0.4 people per square kilometre. It is a true desert with less than 193mm of rainfall a year and average maximum summer temperatures above 35°C.

Spectacular dinosaur discoveries in the Gobi

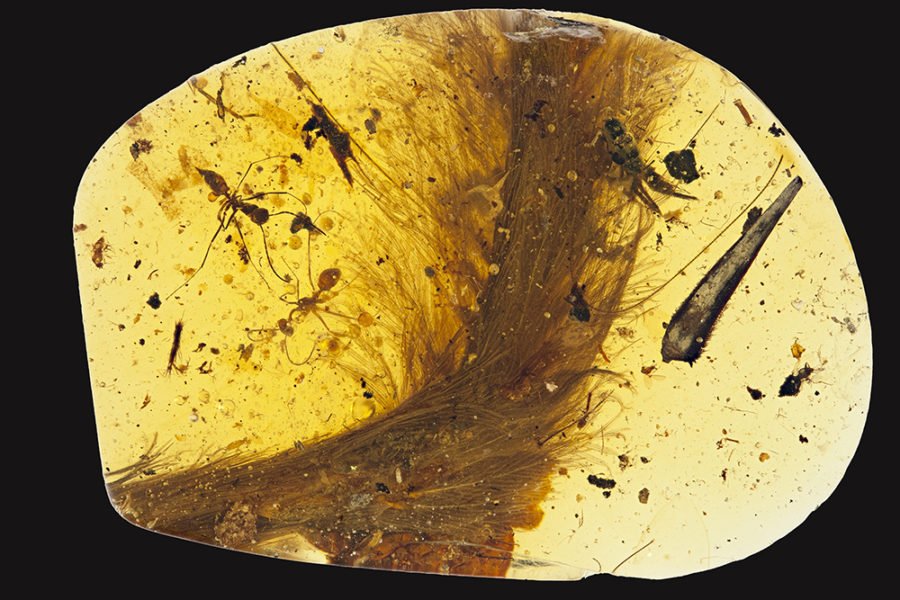

IN RECENT YEARS, a series of feathered species of dinosaurs have been discovered in the Gobi, helping firm up the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds. These include Gigantoraptor, a parrot-beaked ‘oviraptorosaur’, 8m long and 4m tall. Found in the Gobi in 2008, it is thought to be one of the largest feathered animals ever to have lived.

Other oddities include a herbivore named Deinocheirus, almost as big as T. rex, but with massively long 2.5m arms, a weird hump on its back and a duck-like bill, possibly for sucking up aquatic plant matter.

“More than 90 species, a huge number, representing a large proportion of the world’s dinosaurs, have been found in Mongolia,” Tsogtbaatar says. “The Gobi Desert, in the southern part of Mongolia, is a relatively limited area, yet we have found so many kinds of dinosaurs in the last 80 years.”

Early palaeontological forays into the Gobi were led by the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in the 1920s, and were the largest scientific expeditions ever to leave the USA. These must have been quite a sight, with great trains of camels and early motor cars slowly snaking across the landscape.

In this windswept and unforgiving region of Asia they found a great cache of dinosaur bones, with the first specimens of Alectrosaurus, Velociraptor and Protoceratops. At the Flaming Cliffs, which we also visited on our 2015 expedition, they found the first fossilised dinosaur nest with 13 large eggs arranged in a circle.

The AMNH has returned frequently on expeditions with the MAS since the fall of the Soviet Union, and many other important finds have been made, which have revolutionised our knowledge of dinosaurs.

Sitting around the campfire in the evenings, or inside the cosy ger at the centre of our small camp, we had time to reflect on the fact that although we had a few modern comforts, we’d also experienced a little of the incredible thrill of discovery that those pioneering expeditioners first felt when they stumbled across untold fossil riches hundreds of kilometres out into the wilderness of Central Asia.

This is an account of the 2015 AGS Gobi expedition. Want to participate in 2016?