Coober Pedy: outpost in the outback

IT’S JUST AFTER 8AM on a sharp winter’s morning. In Coober Pedy, the famed opal-mining centre 850km north of Adelaide, a handful of dusty utes are spluttering out of town. At the wheel of one is George Kountouris, a former London-based executive and second-generation miner who grew up here.

From the gleaming, gem-filled cabinets in his main-street shop, George and offsider Vince Crisa are driving to a claim 5km out of town to scratch for opal.

A little more than two hours earlier another group of miners left Coober Pedy to begin a day’s digging. This was a 50-strong crew being ferried by bus to Cairn Hill, 55km south-east of town. This mining mob is not after gemstones but truckloads of dark magnetite–copper ore.

Every year about 1.7 million tonnes of the stuff is gouged from this mine’s pit and shipped to China. Meanwhile, another 75km down the line sits the even bigger copper and gold open-cut mine at Prominent Hill. Here a 1200-strong workforce shifts a thumping 8 million tonnes of ore a year.

The sprawling heart of outback SA is a changed place. Over the past two decades a dozen or so large-scale mines have rumbled to life in the gibber and spinifex vastness north of Port Augusta. Although most are discrete, self-contained operations, their shockwaves continue to ripple across the region.

End of the Opal boom

At first glance Coober Pedy seems little altered by all this carry-on. Hutchison St – the main drag – retains its string of opal dealers, jewellery shops, quirky underground motels and pizza bars.

Tom & Mary’s, the town’s legendary Greek taverna, still serves a slap-up seafood platter. For a desert outpost, this town enjoys its surprising daily flurries of visitors, shoppers and traffic.

But in the words of George Kountouris – and almost anyone else with an eye on the opal business: “It’s finished; it’s gone.” From the heyday of the 1970s and ’80s when some 3000 opal miners toiled on their small claims, there are barely 20 still swinging a pick.

Falling prices, rampant costs and a global dip in demand have leached the town of its most colourful lifeblood. “The joke these days,” says George, “is that if someone’s out there doing work they must have had a fight with their missus.”

Coober Pedy has always worn its knockabout heart on its sleeve.

The underground city of Coober Pedy

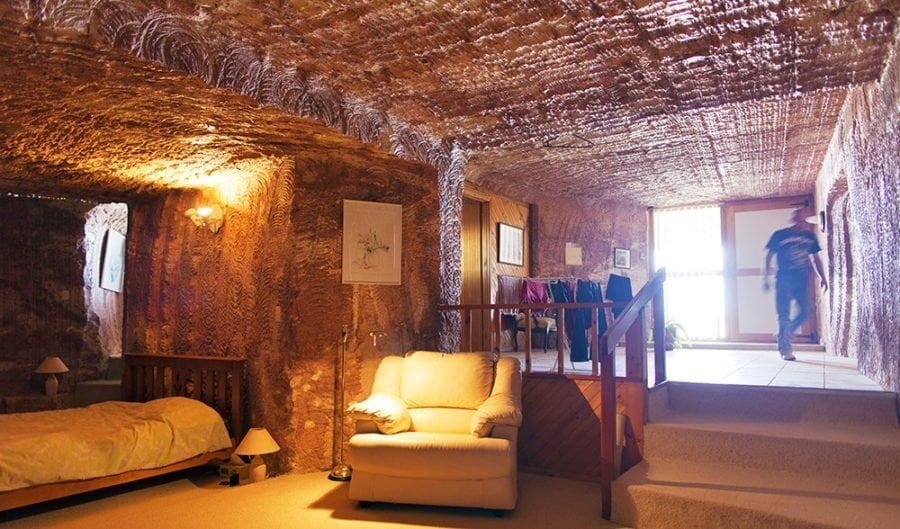

This topsy-turvy settlement grew up among a cluster of old mine sites. Its streets dip and sway past mullock heaps and eroded gullies. And apart from the very proper-looking Westpac bank and a few government offices, the place has an authentic, makeshift feel.

Every side road sports its share of busted machinery, old tyre stacks and lean-to sheds. It’s like one big, dust-filled backyard. Needless to say, the Tidy Town judges are not booked in anytime soon.

Then again, in this of all places, the view at street level rarely tells the whole story. Take, for example, the fact that more than half the 3500 locals live out of sight in neat-as-a-pin dugouts underground. Burrowed deep into the hillside slopes, some of these cool, multi-room residences are as spacious and luxurious as any in a big city. Suburbia doesn’t get earthier than this.

An even more telling perspective is from 1000m above. At that elevation the town recedes into a red expanse riddled with drill holes and embossed with conical tailing mounds or mullock heaps, shaft entrances and huge ramps of excavated material. It’s an oddly mesmerising vision.

At close to 50,000ha, this entire surface appears like a work of abstract art or a vast natural wonder. But in truth, this colossal sculpture of desert dirt is essentially hand-wrought. For an entire generation of hard-bitten miners, here lies their field of dreams.

Coober Pedy’s social frontier

Today, from the air, signs of activity are scarce. However, one of the puffs of dust below is coming from Emu Field and a big Daewoo 300 LCV excavator with George at the helm. He’s scraping the Daewoo’s bucket down the side of an open hole no bigger than a one-car garage.

Having exposed a new surface, he and Vince peck away with their hammers, hoping to find twinkling veins of opal nestled among the drab host rock.

“So this is what we do all day,” explains George. “Patience, you’ve got to be patient. And looking – always looking.”

George’s keen eye for opal was handed down from his dad Constantinos, who started mining here in 1967. While opal was discovered at Coober Pedy in 1915, it was another 45 years before things started humming with a surge of families arriving from southern and eastern Europe – especially Greeks, Italians, Yugoslavians and Germans.

“A lot of Europeans came up here to escape the factories,” notes George. “It was hard-going early on. Everyone lived out on the field and the dugouts were pretty rough. They had to cart water in those days. But they had hope. Back then the whole town shared this dream – it lived with everyone.”

Isolation, shared struggle, the dream of a big find – such were the forces binding family and community. By the 1980s more than 45 nationalities were living – and digging – shoulder to shoulder here.

It was a freewheeling experiment: a mostly self-righting social frontier. Long before the concept got a name, Coober Pedy flourished as one of the nation’s most surprising multicultural triumphs.

Kicking back with the locals

The Italian Miners Club is a popular hilltop haunt for a Thursday night feed, a beer and a spot of sunset-viewing. In a typically ‘Coober’ twist the club committee is mostly Australian and for 20 years perky, Czech-born Mila Kovacek has been manager.

Like many long-time locals, she misses the openness and buzz of the early years. “Opal mining is just like gambling. You have a go. You never know what you might find,” says Mila. “And when they found opal they kept gambling. Here I was earning $17 an hour and they would drop 60K on a card game.”

Many arrivals were drawn to the town’s remoteness and refuge. Before the advent of street signs and officialdom, these blow-ins grabbed the chance to ‘get away from stuff’. It was a footloose, no-questions-asked sort of place. Often rough and seriously tumble, too.

Miners pushed their luck above and below ground. Shaft collapses, injuries – and worse – were part of life on the fields. And back then explosives weren’t just a tool of trade but occasionally a way to settle a dispute or send a message. Even the local courthouse copped a blast while under construction.

Changing times and open cut mining

Those wild west days are gone. But so too has much of the community’s flair for out-there socialising.

The arrival of satellite television is often cited as diminishing the town culture. Ditto drink-driving laws. To many locals, life now seems secretive and less friendly as people retreat more into their dugouts.

Yet perhaps the real driver for this new mood is simply the fraying of a common thread that kept people close. As Mila observes: “It’s all changed. There aren’t the risk takers; no-one is mining opal.”

Steve Baines, Coober Pedy’s Mayor for 14 years, agrees: “The younger generation are just not coming through. Then again, why would you risk going to look for opal when you can travel 40km down the road and earn $40 or $50 an hour?”

Some townsfolk like Mila view the big, open-cut mines, and especially those with a fly-in fly-out workforce, as a threat to the town’s traditions. Others take a more pragmatic line.

“The Cairn Hill operation has given us the greatest benefit by accommodating their miners in town,” notes Steve. “Then again, most of these mines have created some opportunities that wouldn’t have existed otherwise. Not just employment but sponsorship and work for local contractors, sign writers, concreters, waste services, and so on.”

Coober Pedy’s no longer a town in isolation

There’s another reality, too. Year by year Coober Pedy grows a little less isolated. Technology is tugging the community closer to the outside world. The region’s raw edge of remoteness has also certainly faded since the sealing of the Stuart Highway in 1987.

With that the town has branched out as a government service hub and stopover for wandering tribes of backpackers and grey nomads.

Local tour operator Wayne Borrett sees the change: “These days it’s not just the uniqueness of town or the opal. People are also switched on to the whole landscape: the Breakaways, the Painted Desert, Lake Eyre, the Simpson, William Creek – the lot.”

Coober Pedy is poised at the crossroads. As well as the main north–south run, there are the desert travellers lobbing in from the Anne Beadell Highway, the Oodnadatta Track and all points beyond.

Keeping a watchful eye over this vast swathe is local top cop Pete Murray and his 18-strong team. Since arriving in 2004 he’s tracked the town’s shifting identity with more visitors, less wealth and an ageing population. But the old-style tolerance lives on.

“Coober Pedy is still the most egalitarian place I’ve ever been… You can be a local here in 10 minutes.” Another highlight for Pete is the role of indigenous blokes in local policing. “A number of Aboriginal guys are moving from their jobs as community constables into full academy training and mainstream police work.”

Indigenous community of Coober Pedy

A tight-knit aboriginal community has always been part of Coober Pedy life. For many families it’s a meeting place and a centre for work and sport. Originally from SA’s west coast, Chris Warrior is both an affable senior community constable of 10 years standing and, no less importantly, coach of the local footy team.

Formed in 2004, the Coober Pedy Saints is a classic many-cultured expression of the town. With true outback commitment – aside from four home games – the team makes a 900km round-weekend-trip to Roxby Downs to play in the Woomera and Districts competition.

The strength of diversity is reflected within many Aboriginal families. Local artist Katrina Williams is one of five sisters, all of whom live in Coober Pedy and carry on a family tradition.

“My grandmother was from here but grandfather’s people came from Utopia in the Territory. All his family paint and so do we,” says Katrina, as she gazes across a bright bushtucker painting that’s big enough to cover her dining table. “It’s what we do when we get together. I was crap at first but it didn’t take long. It was like I had it in me.”

The art success of the Williams sisters is another marker of the opportunities this far-flung town continues to offer.

Opal mining may have lost some of its lustre but Coober Pedy’s unique amalgam of ethnic groups still shines.

Continuing appeal of Coober Pedy

Among the influx of recent years are more than 90 Sri Lankans.

Shanaka Hewage has been working for three months at the local IGA supermarket. For him it’s all about the future. On the eve of his return to Sri Lanka’s capital city, Colombo, he’s clearly looking forward to bringing his wife and two children to their new outback home.

“It’s the best place for my family. There are other Sri Lankans – that’s wonderful. But the whole community, we are all together, so many nationalities.”

Susie Crisa first caught sight of Coober Pedy as a six-year-old, when her family moved here in 1971. “I remember arriving here on the bus… I woke up, looked out the window into all that empty desert and just cried,” she recalls with a wry laugh. The plan was to come for a year, make some money and go back to Greece. “That year became 31 years.”

Now the local manager of Aboriginal Family Support Services, Susie’s personal story resonates with many others who grew up here, travelled, lived away and yet keep coming back.

“Coober Pedy is still quite rough and raw in certain ways,” she says. Through her job she’s witness to the trans-generational trauma that affects some Aboriginal families.

“The drugs, alcohol and family breakdown are just symptoms of a deeper problem. It really affects me – it’s devastating. We have to be much more proactive.”

At the same time, for somebody with Susie’s feeling for social justice, a town with a history like Coober Pedy’s still holds the promise of making a difference.

“You have a microcosm of the global world here. And we do it pretty well. This is a town that gives. People give of themselves and sacrifice to make things happen. It’s not the mining or the dugouts or the tourism. The real opal here is the people.”

That said, even today and with all the changes, there’s no escaping the insidious part that opal still plays in shaping the locals – that roguish glint in the eye that says Coober Pedy.

Opals still driving residents at Coober Pedy

George Kountouris left the high-flying life of a London advertising creative director to come back. “It was meant to be a brief visit,” he admits.

“But then I said to my dad, ‘I think I’ll bring a machine up and do some mining.’ I’ve been here ever since. It’s the dust – it’s addictive.”

Another wanderer-cum-second-generation miner is Markus Hammermeister, of Swiss descent. For five years he and his business partners Keith and Shirley Wreford have been moving mountains 20km north of town. With a front-end loader Markus tips huge bucket-loads of mullock into a massive sifting machine.

It’s called noodling – the dream that stray, overlooked gems will appear out of the second-hand rubble and billowing dust.

“I just like the opal,” confesses Markus. “When you see something nature can make so good… It’s not the money, not with all the costs and hours. It’s what you know; what you like doing. Then there’s the desert and the space. Where else do you go if you want to live this free?”

The full story can be found in Australian Geographic #111.