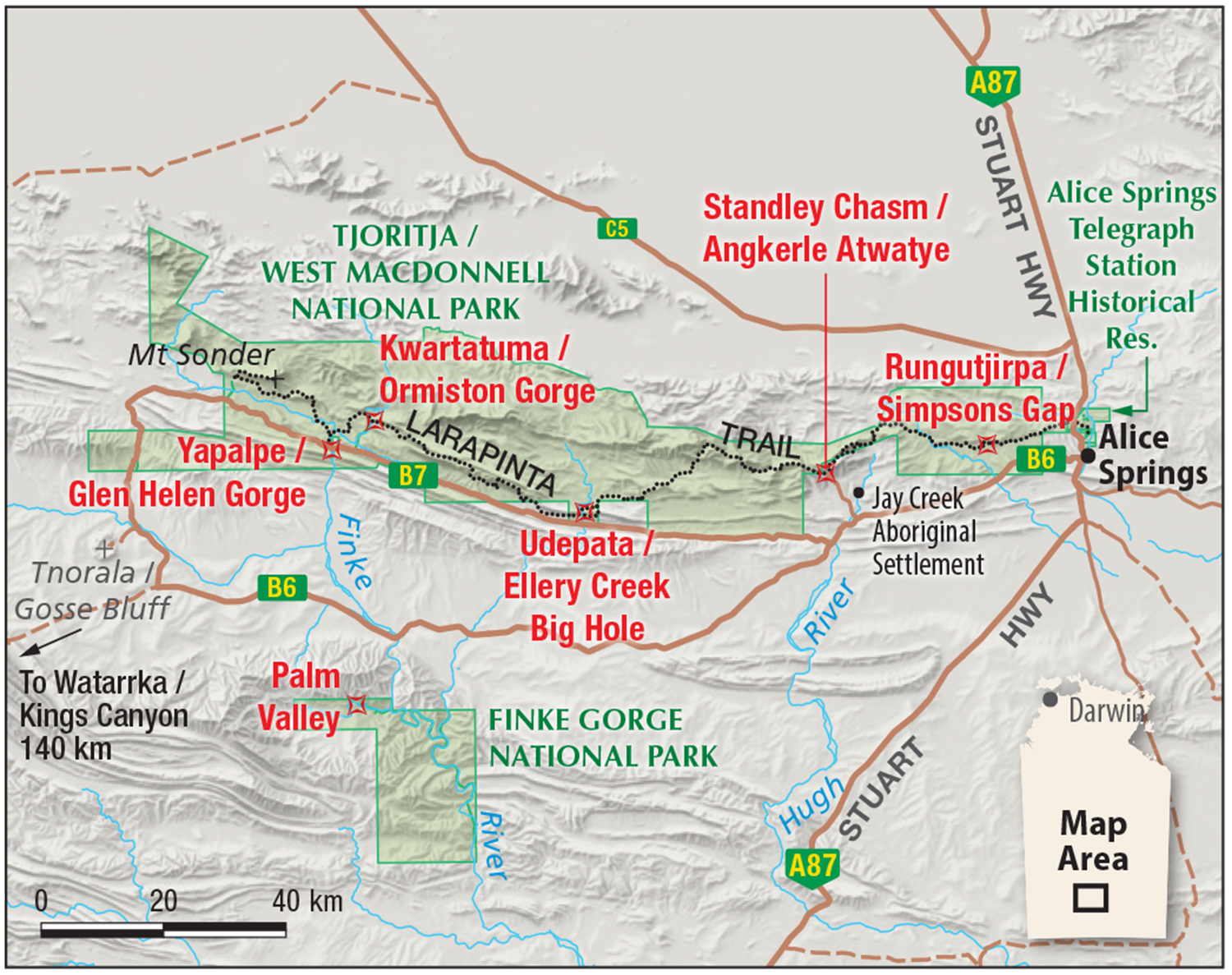

It’s minutes before midday as we approach the entrance to Standley Chasm/Angkerle Atwatye, about 50km west of Alice Springs. Our guide has timed our arrival perfectly to witness the natural spectacle for which this site is famed. Every day about now, depending on the season, sunlight floods this tall, narrow gorge, illuminating its craggy cliff walls with glowing hues of deep orange and red.

Carved into Tjoritja/West MacDonnell Ranges, this 3m-wide, 80m-high chasm cuts through quartzite – a hard rock that began here as layers of sand from the floor of an ancient sea. Compacted under pressure, this sand fused into sandstone. During a later period of intense tectonic activity these sandstone beds hardened, metamorphosing into the quartzite.

Then, 400–300 million years ago, during a tectonic event known as the Alice Springs Orogeny, enormous forces buckled and tilted these once-horizontal beds of quartzite, flipping them vertically. This allowed for rainfall, although scarce in the desert, to weather exposed fractures between layers, eventually sculpting the chasm. These were the same forces that squeezed the entire region, forming the whole MacDonnell Ranges.

Standing within the chasm hundreds of millions of years later is like being in a time capsule. The walls reveal a cross-section of geological layers. Bands of dark and light mark changes in mineral content and sediment, each layer recording a chapter in the story of this land. Some contain ripple marks, relics of waves that once lapped across the inland sea. This incredible natural formation is now one of the region’s most popular visitor drawcards, especially for photographers keen to capture the midday light spectacle.

Cultural significance

Long before Standley Chasm/Angkerle Atwatye became a tourist magnet due to its geological beauty, the site was, and continues to be, a place of deep significance to its Traditional Custodians, the Western Arrernte people.

Here, for tens of thousands of years, they held ceremonies, including initiation and rites of passage rituals. Elders used the chasm as a place to pass down knowledge of Country, of laws of kinship, and of songlines, this landscape being an integral part of Dreaming stories.

In both the chasm itself and the valley in which it sits, the Western Arrernte hunted and foraged for native foods, and gathered bush medicines. The chasm offered shade from the sun and shelter from harsh weather.

“In short, Standley Chasm was not just a scenic gorge; it was a living cultural landscape where law, spirituality, food gathering and survival were intertwined,” explains the site’s operations manager Rosie McKenzie.

The chasm is particularly special to Western Arrernte women, providing a safe birthing place where men were not, and are still not, allowed.

“I get goosebumps every time I come near it,” says our guide, Pertame man Brodie Roesch. He explains that the off-limits sacred birth location is just beyond where we’re standing, around a corner in the chasm’s northern section. This is Brodie’s grandmother’s Country.

After European settlement, the land including and surrounding the chasm and its valley was taken and used for pastoral farming. Later, beginning in the 1930s, it passed through the hands of various leaseholders who operated the site as a tourism enterprise.

Return to Arrernte

In the early 1990s modern ownership and management of the site was returned to the Western Arrernte community that, through the Angkerle Aboriginal Corporation, still owns and operates it.

Brodie is one of a group of Standley Chasm/Angkerle Atwatye Cultural Guides, who maintain their own connections to the site while sharing it and its stories with visitors from the wider community. As we walk back through the valley after the chasm’s midday show, he explains the Arrernte culture, its traditions and kinship system, and how his people once lived. He points out the abundance of different plants that provided his people with food and medicine.

For example, there’s the corky-barked Inarnta/beantree (Erythrina vespertilio), its fruits used for eating, medicine and even jewellery-making. Coolamons (bowls) were also carved from its trunk. “Men asked permission to cut it down to make it into shields,” Brodie adds.

Also growing here are 24 species of native lemongrass used in bush medicine to cure everything from chest colds to constipation. “Mixed with water it makes an electrolyte drink,” Brodie says. “It’s like nature’s Gatorade.”

For a quick energy boost, Brodie says nothing beats the sugary lerp (a hardened insect secretion) collected from the leaves of the Para/river red gums (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) that are towering above us. The termite-resistant wood of the Para was also used for making tools.

Brodie stops beside an Arrkunpa/desert bloodwood (Corymbia opaca), explaining that the antiseptic properties of its resin are used for treating wounds

“The bright red resin was also used for tanning kangaroo skins, [and] for water-carrying bags,” Brodie says. He then points out some small, knobbly, woody balls in the branches above. These galls – abnormal growths on plants – are created by a species of scale insect (Cystococcus pomiformis) and are known as Merne arrkunpa/bush coconuts, or bloodwood apples. Inside, the adult female insect lives surrounded by a white flesh that provides food both for herself and for her growing offspring.

Brodie explains how nutritious this bush tucker is. Once the gall is picked and cracked open, its contents are a true superfood. “It’s a good protein snack to get through the day,” Brodie says. “It tastes like coconut with a hint of eucalypt.”

We continue on, past Yinpara/spearwood trees (Pandorea doratoxylon) with flexible stems that Western Arrernte men used to make spearshafts. We see many different species of wattle (Acacia spp.), their seeds eaten raw or cooked, or dried to make flour. Then there’s the white cypress-pine (Callitris glaucophylla) – used to build spears, spear throwers and ceremonial objects.

The list goes on. As we walk with Brodie it seems that for every tree, every plant, he has a story to tell of how each was used by his ancestors. Standley Chasm/Angkerle Atwatye is also home to a plethora of native bird and wildlife most readily spotted at dawn or dusk. One notable species is the Central Australian black-footed rock-wallaby (Petrogale lateralis centralis).

Water is life

Why is flora and fauna so abundant here, in the middle of the Australian desert? It’s thanks to two things that guarantee a permanent year-round water source. One is the natural Angkerle Spring, just south of the chasm, which is fed by numerous aquifers scattered throughout the valley. The other is the placement of the valley within a natural catchment that channels rainfall into the gorge.

Seasonal downpours funnel through the chasm, flooding the valley floor and replenishing its pools. Brodie explains that even in areas where we can’t see the water, it only takes a bit of digging to reach it. And the best bit is that it’s naturally filtered, pure and ready to drink.

As our guided tour reaches its end, Brodie has one more fascinating story up his sleeve: that of the Tywekekwerle/MacDonnell Ranges cycad (Macrozamia macdonnellii).

“Tywekekwerle translates to ‘someone else’s story’, because it belongs in the Tropics,” Brodie says.

Most cycads in this genus are found in higher rainfall regions of eastern Australia, so their presence here in the desert is extremely rare. This endemic species is a living remnant of the ancient Gondwanan rainforest, clinging on in a handful of sheltered gullies, slopes and river edges of the MacDonnell Ranges – long after the surrounding landscape turned to desert. Other smaller colonies exist nearby in Palm Valley and Watarrka/Kings Canyon, but the Standley Chasm/Angkerle Atwatye colony is the most abundant, healthy and concentrated.

I walked into this valley excited to see the chasm’s famous fiery walls but left with a much deeper appreciation of the site as a whole. It was a truly illuminating experience, in both the literal and metaphorical sense.

Candice travelled as a guest of NT Tourism and took part in the three-hour Aboriginal Guided Tour & Talk, but there are a variety of unique activities visitors can explore associated with Standley Chasm/Angkerle Atwatye, including traditional art, cooking and weaponry workshops. Self-guided options are also available, as well as overnight camping. More info: standleychasm.com.au