It’s late evening and I’m travelling in a small bus, surrounded by complete darkness. Even the vehicle’s headlights are turned off as the driver navigates an unsealed road winding up the side of a mountain.

But why would the headlights be turned off in such a seemingly precarious situation? Because we don’t want to emit any light pollution that would obscure the view of the night sky.

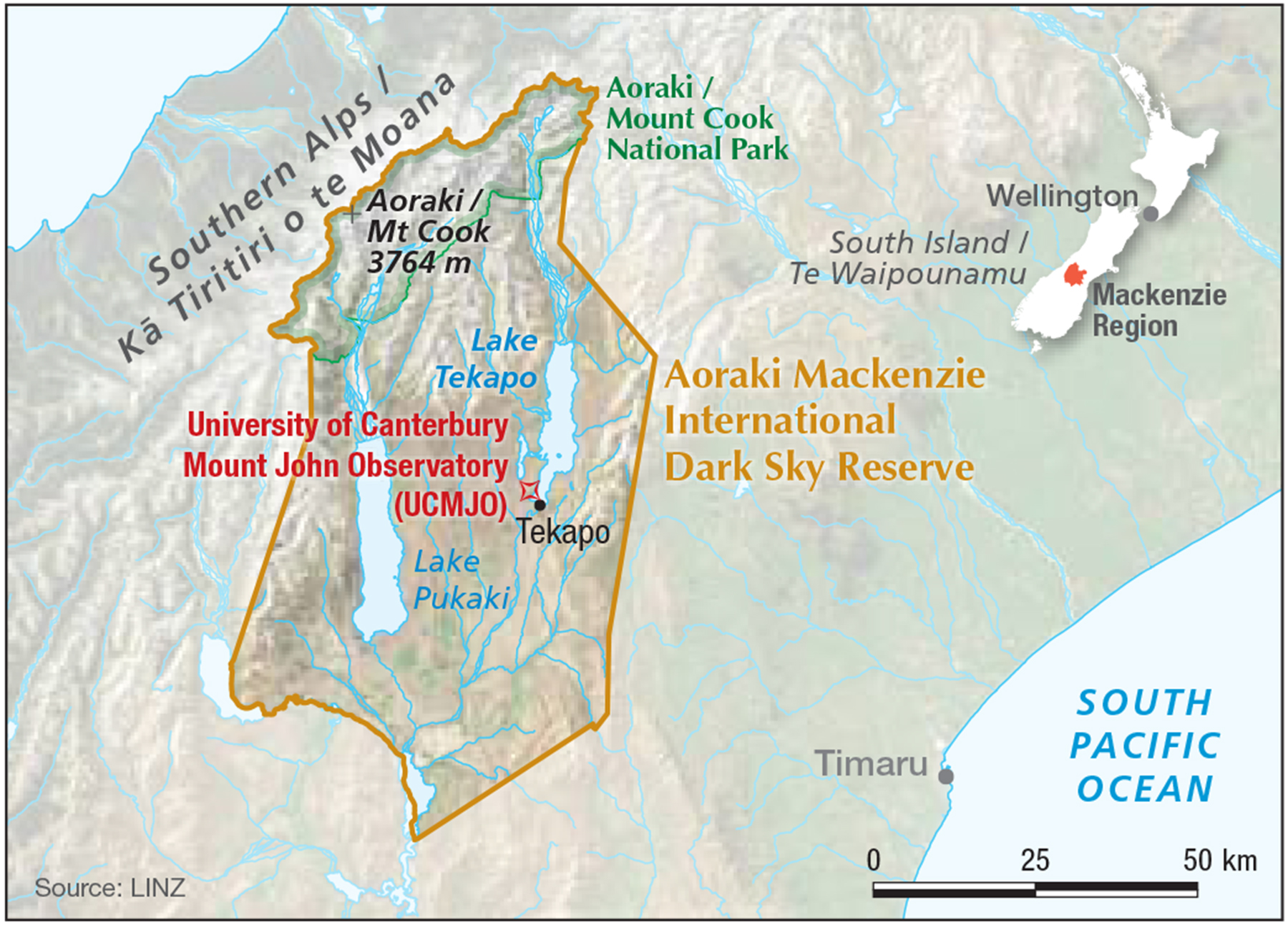

We’re on our way to the University of Canterbury’s astronomical research centre. Here, 1029m above sea level atop Mt John on New Zealand’s South Island, the skies above are some of the clearest in the world. The area is officially recognised as a Dark Sky Reserve – the largest in the Southern Hemisphere.

Granted its status in 2012, the Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve covers 4367sq.km and encompasses national parks, farming land, private and public land, and whole townships.

Accreditation is bestowed by DarkSky International, the independent organisation that oversees the International Dark Sky Places program and provides certification to places – everything from large protected areas to communities, parks and urban locations – that “preserve and protect dark sites through responsible lighting policies and public education”.

It’s part of a wider movement to acknowledge the night sky and nocturnal environments as naturally, culturally and historically important – worthy of conservation.

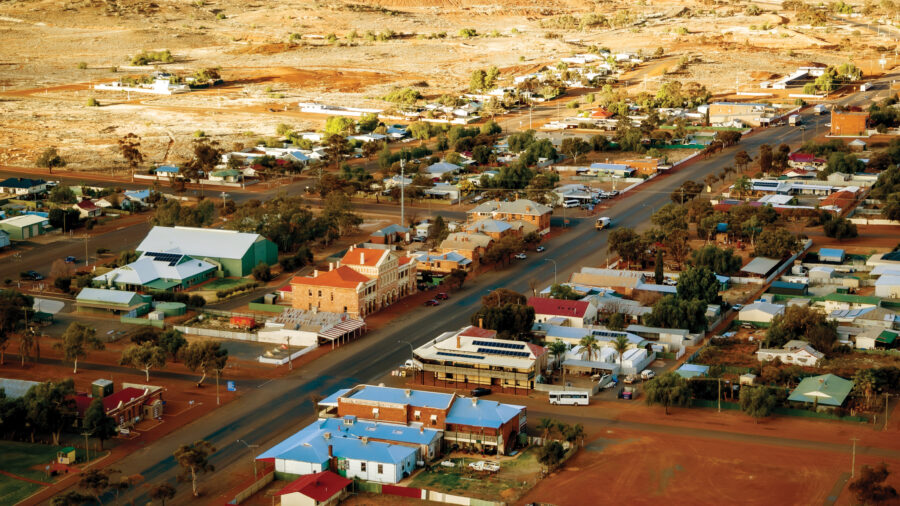

Australia has its own Dark Sky Places, including three in South Australia – Arkaroola Dark Sky Sanctuary, River Murray Dark Sky Reserve, and Carrickalinga Dark Sky Community. Elsewhere, there’s the Jump-Up Dark-Sky Sanctuary in Queensland’s Winton, and Warrumbungle Dark Sky Park in New South Wales.

Back on the bus, the carpet of stars above is already putting on a spectacular show – and we haven’t even officially started our stargazing experience yet. Each passenger has fallen silent, noses glued to the windows as a soundtrack of celestial-themed songs play over the speakers. Think Frank Sinatra’s ‘Fly Me to the Moon’, Simply Red’s ‘Stars’, The Beatles’ ‘Across the Universe’, Elton John’s ‘Rocket Man’, Madonna’s ‘Lucky Star’, and of course, David Bowie’s ‘Starman’. This might sound quite contrived, or even a little naff (and it kind of is!), but when Moby’s ‘We Are All Made of Stars’ comes on, I’m completely sucked in.

People, they come together

People, they fall apart

No one can stop us now

’Cause we are all made of stars

These lyrics remind me of something that happened earlier in the day. Turn back the clock several hours and I’d just arrived at the Dark Sky Project headquarters on the shorefront of Lake Tekapo. Tekapo is the tourism hub of the region and the most popular base for visitors embarking on the area’s ‘astro adventures’ – of which there are plenty.

The biggest player in town is the Dark Sky Project, the first astrotourism operation in the area. It was founded in 2004 by Graeme Murray and Hide Ozawa – Tekapo locals who were also instrumental in acquiring the region’s Dark Sky Reserve status.

Now co-owned by Ngāi Tahu Tourism – Ngāi Tahu being the largest iwi (Māori tribe) in Te Waipounamu (the South Island) – the Dark Sky Project offers experiences from both scientific and cultural perspectives.

Its mission is to ignite a passion for the dark sky and invoke a concern for its preservation. Visitors learn about the importance of darkness to human health and the environment.

I’m here for the Dark Sky Experience – an indoor multimedia immersion allowing for night-sky exploration during the day. Bringing together Māori astronomy (tātai aroraki) and Western science, it’s during this guided tour that our expert explains how every one of us in the room is made of stars – literally.

Essentially, the human body is mostly made up of elements that were formed by fusion in the cores of ancient stars. When these stars died, supernova explosions scattered the elements across the universe and, over billions of years, these elements combined in various ways to create new stars, planets, and eventually, life – meaning Earth, and everything on it, is made from those recycled star materials.

It’s not just poetic. It’s scientific.

This stayed in the forefront of my mind all afternoon. And while Moby’s song is a metaphor for the interconnectedness between humans, hearing these lyrics while looking up at the night sky, in the context of what I had learned, caused me to feel an overwhelming connectedness to the stars themselves that I had never felt before.

The bus has reached the summit, and we pour out onto the gravel car park. Mt John Observatory has been here since the 1960s, long before the concept of Dark Sky Reserves or the now-booming astrotourism industry.

“A survey of New Zealand was done, and Mt John was [found to be] the most favourable site,” says Steve Butler, chair of the Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve.

Mt John is in the Mackenzie District of South Canterbury, where the area’s natural attributes provide some of the clearest night skies in the world.

Steve explains the importance of the intermontane (between-mountains) plateau. “[It’s] a glacial outwash enclosed by mountain ranges, and the alpine air environment provides a good weather pattern for astronomy,” he says. “There are high levels of fully clear [completely cloudless] nights.”

Because of this, measures have been taken to reduce human-caused light pollution that would compromise the area’s natural dark skies.

The most obvious example is the design of streetlights. Bulbs are fully shielded by covers that direct the light downwards. These covers are mandatory for all outdoor lights in the area – on both public and private property.

“The district plan states all new light fittings installed must be fully shielded, lighting only downwards and not upwards or to the side,” Steve says.

Other lighting ordinances include limits on blue-light emissions. “The reason for that is that the blue portion of the lighting spectrum scatters very readily in the atmosphere and causes a big glow to form over a city or a town. It’s the same reason the sky is blue in the daytime – the blue portion of the light in sunlight scatters more readily,” Steve says.

An overwhelming majority of locals have welcomed these lighting regulations, eager to see their community benefit from the influx of visitors the dark skies bring.

“I think it’s brilliant,” Steve says. “Eighty-six per cent of the world’s population can’t see the night sky. So, there’s a booming industry all around the world, and it’s a tourism stream where there’s very little impact.”

The regulations protect the unobstructed, 360° view of pure night sky that’s visible from Mt John – and which makes Dark Sky Project’s Summit Experience so special.

Our guide takes us for a walk through the working observatory’s buildings and domes, stopping along the way to share the science and stories of the constellations above. Then, it’s time to venture deeper.

We use high-powered telescopes to focus on everything from the Milky Way to far-off star clusters, planets, whole solar systems and even distant galaxies, learning about each as we go. But the real treat is access to the University of Canterbury’s 16-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope, housed within its own fit-for-purpose private observatory dome.

Of all the mind-blowing celestial wonders we see, my favourite is the ‘Jewel Box’ cluster (officially named NGC 4755, if you want to get technical). Nestled within the Southern Cross constellation, this open star cluster is only about 16 million years old – quite youthful in stellar terms! About 6500 light-years away from Earth, this group of about 100 stars looks like a single star to the naked eye.

It’s through the telescope that its striking colours become visible. With a mix of bright and faint stars, contrasts of pale blue and orange, and a solitary ruby-red supergiant at its heart, it’s like peering into a jewel box.

When the experience comes to an end, we make our way back to the bus and I reflect on everything I’ve learned, seen and felt throughout the day.

The Dark Sky Project has a motto: “They say it takes a village to raise a child. We say it takes a village to protect the stars.”

This is certainly true of Tekapo – a small, remote New Zealand community that has banded together to protect something that’s bigger than all of us, but yet fundamentally part of us.

After all, we’re all made of stars.

Candice travelled as a guest of Mackenzie Region NZ.