A land shaped by fire

This article is brought to you by Coral Expeditions.

I wake to the gentle sway of the boat. A rush of excitement pulls me out of my hazy morning dreams as I remember where I am. Drawing back the shutter, I look out at remote South West Tasmania – a place I’ve always wanted to visit and see with my own eyes. Still, crystal-clear waters reflect the mountains rising from the landscape. The quietness of the scene is beautiful.

I’m lucky to be waking in this special place that rarely sees humans anymore. Yet this is a place steeped in First Nations culture and history, its landscapes shaped over millennia by First Nations peoples.

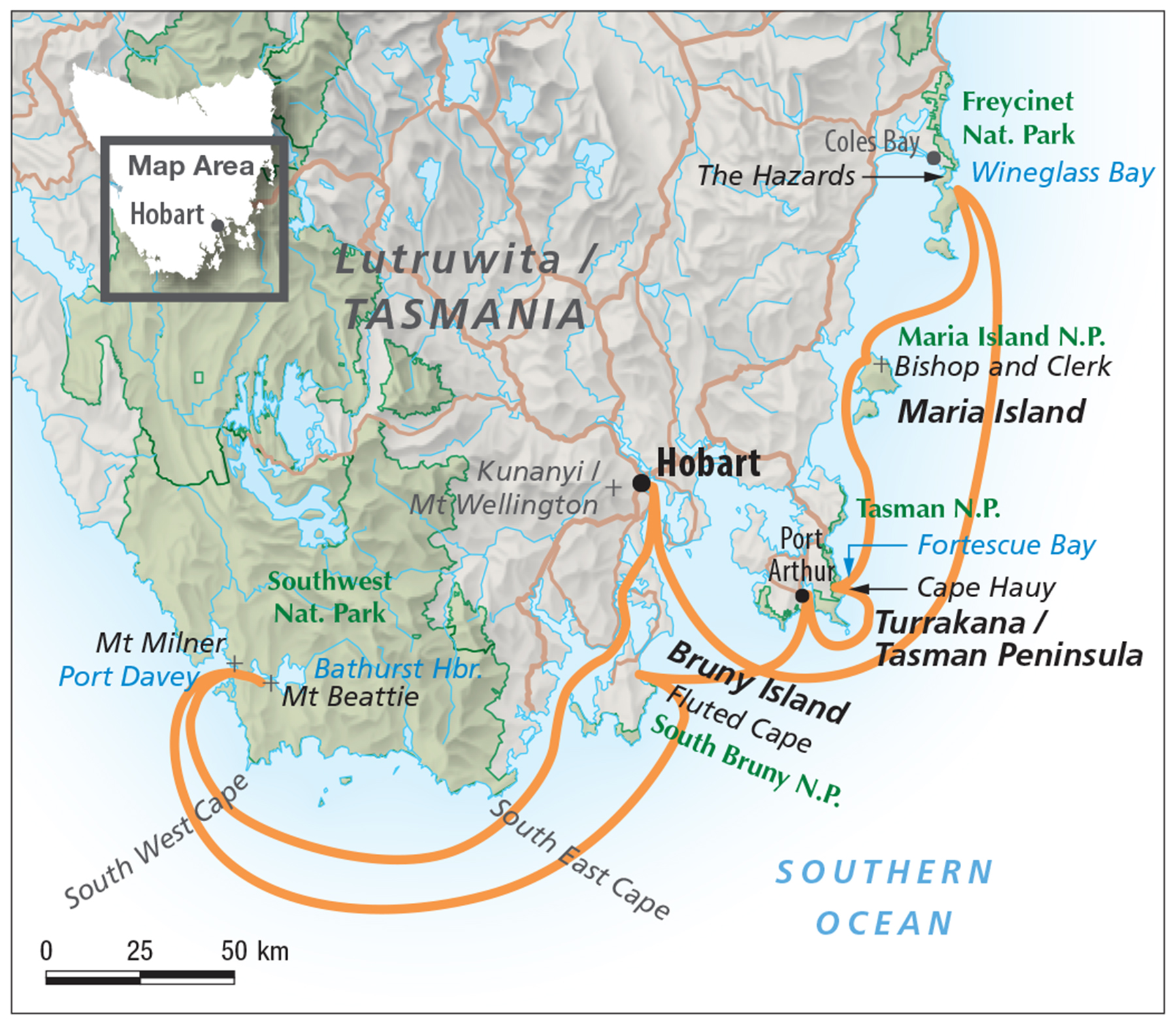

I’m exploring Tasmania onboard Coral Expeditions’ Coral Discoverer. We boarded at Hobart last night before setting off on a tour of some of the Apple Isle’s most iconic natural sites. This luxury cruise ship will be our base for the next 10 days as we steam around Tasmania’s south-western and south-eastern coasts by night and explore its remote and remarkable landscapes by day.

We set off for our first mountain of the trip: Mt Beattie. This beautiful peak rises out of Bathurst Harbour and overlooks Mt Rugby. The rugged Western Arthur Range stands on the horizon. Mt Beattie’s quartzite peak is 276m tall and offers expansive views in all directions. The scenery is made all the more impressive by the biodiverse foreground of buttongrass moorlands dotted with flora. Think fan-shaped purple fairies’ aprons (Utricularia dichotoma) and vibrant-red pygmy sundews (Drosera pygmaea), their trichomes glistening in the sunlight like tiny gems. The evolutionary history of these carnivorous plants is as fascinating as their colours and forms.

Not long after reaching the top of Mt Beattie I realise how many photos I’ve taken. As much as my instinct is to capture all these wonders with my camera, I remind myself to stop and be present. In our fast-paced society, it’s a special treat to experience a remote wilderness like this.

Past and present connections

Bodies tired and minds quiet, we make our way back to the Coral Discoverer feeling mesmerised by the mountains that are now perfectly mirrored on tannin-rich Bathurst Harbour. The boat’s engines awake, distorting the mountains’ reflections in a gentle and hypnotic way. Pure magic.

Over the next few days we explore deeper into the buttongrass moorlands, which are intrinsically connected to the Palawa First Nations people of Lutruwita/Tasmania and, in the Melaleuca and Port Davey areas specifically, to the Needwonnee clan. If only they were here to tell the stories of the land and share knowledge of how to care for this country.

I reflect on how I wish we could still connect with nature in a meaningful way by working alongside it, treating it with respect – at best, even treating it as equal.

One person who heeded the Needwonnee peoples’ traditional knowledge was the legendary bushman Deny King. He used patch mosaic burning to manage the landscape, ensuring certain areas were touched by fire at different times. This ancient method of cool burning, or firestick farming, helps sustain the rich biodiversity of Melaleuca’s buttongrass moorlands.

This fire management has prompted the return of the orange-bellied parrot (Neophema chrysogaster) – one of Australia’s most critically endangered bird species – into the area.

The orange-bellied parrot is the world’s smallest migratory parrot species. Each summer, it makes its way to Melaleuca’s buttongrass to breed. It’s a special sight to see these colourful parrots here. Less than 100 are thought to exist in the wild today, and this is where they choose to be.

Progressing East

A slight heaviness fills me as we leave my new favourite place in Tasmania, but I’m soon reminded the adventure has only just begun.

Our next stop is Bruny Island, an old favourite of mine. Rugged Jurassic dolerite cliffs of the Fluted Cape tower some 270m above the ocean. Centuries-old Tasmanian blue gums (Eucalyptus globulus) rise out of the Permian soils at the base of the cliffs.

As we wind our way up our scenic hike, the trees soon switch to messmate stringybark (Eucalyptus obliqua), with an understorey of spiny-head mat-rush (Lomandra longifolia) and sweet bursaria (Bursaria spinosa). The sweet bursaria’s flowers attract common brown butterflies (Heteronympha merope), which weave in and out of our group. We don’t need to stop to smell the flowers – the scent flows freely through the crisp morning air.

Witnessing the raw beauty that surrounds us, I realise this is another area equally as rich in threatened species as it is First Nations culture. The connection between the decline of species and the loss of this land’s people and culture is glaringly obvious; they are one and the same.

Sailing further east on the Coral Discoverer, we pass fish farms nestled in the bays. Mike Sugden, a guest lecturer onboard the Coral Discoverer, is a marine scientist, zoologist and avid diver with encyclopaedic knowledge of all things aquatic. He explains the ecological impact of salmon pens on local marine ecosystems.

We sail past Tasman Island and are greeted by fur seals resting on the island’s flanks. Albatrosses glide past effortlessly.

Later, when we settle downstairs for dinner, we spot a pod of common dolphins (Delphinus delphis) outside the ship’s windows. They put on an impressive show for us, surfing and jumping in our wake. It’s the perfect end to another unforgettable day.

Lessons to be learned

After visiting Fortescue Bay and World Heritage-listed Port Arthur Historic Site, we explore another incredible island: Maria Island, which brims with both fauna and history.

Within minutes of stepping onto the island, we’ve seen several marsupial and bird species, from Bennett’s wallabies (Notamacropus rufogriseus) and long-nosed potoroos (Potorous tridactylus) to green rosellas (Platycercus caledonicus) and yellow-tailed black cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus funereus).

When we begin our hike to the summit of Bishop and Clerk, a fluffy wombat greets us on the walking path, its joey visible in the back of its pouch. Welcome swallows (Hirundo neoxena) dart in and out of our group as we make our way past Permian limestone cliffs filled with ancient marine fossils. We continue walking towards the dolerite outcrop, which rises 380m above the turquoise ocean below.

The hike to Bishop and Clerk is spectacular. When we reach the summit, we watch wedge-tailed eagles (Aquila audax) soaring below, patrolling the coastline against a backdrop of ancient flora. The 300-million-year-old genus Cyathea is sandwiched between two impressive dolerite columns, which are both speckled with lichen.

Time seems to move more slowly at the summit of Bishop and Clerk, surrounded by ancient Gondwanan forests. Thanks to Tasmania’s relatively cool climate, ancient Gondwana species have survived in small pockets here, clinging on as the climate shifts. And here on Maria Island they’ve teamed up with more recently evolved (in the grand scheme of things) eucalyptus forests. It’s a haven for native birds, mammals and insects.

What a dream it is to explore so many different wild places along Tasmania’s coastline – so full of biodiversity, and lost stories of cultures and history.

Tasmania is a place that needs to be seen and experienced to fully appreciate its beauty. It’s so much more than can be captured in images or words; it’s a land full of natural wonders and awe-inspiring evolution. This ancient land connects us to the past, and there’s much we can learn from what we’ve lost. But here, at the bottom of the world, these species live on after many millions of years. It’s not just a place to visit but also a place to protect.

This article is brought to you by Coral Expeditions.