This seabird prefers to poo while flying

When Dr Leo Uesaka strapped small cameras to the bellies of 15 seabirds, and pointed the cameras backwards, he had no idea what direction his research was about to head in.

“I was studying how seabirds run on the sea surface to take off, [but] while watching the videos I was surprised that they dropped faeces very frequently,” said Dr Uesaka, a seabird researcher from the University of Tokyo.

“I thought it was funny at first, but it turned out to be more interesting and important for marine ecology.”

Dr Uesaka studied the defecation habits of the streaked shearwater (Calonectris leucomelas), a migratory seabird species known to visit northern Australia, and found that of the 195 bowel movements caught on video all but one was excreted while the birds were in the air, usually soon after the birds’ take-off from the ocean surface.

The immediate question he asked was, “Why?”

Dr Uesaka’s research has just been published in the journal Current Biology, with the hypothesis that seabirds choose to poo from the air to help keep their feathers clean and avoid attracting predators such as sharks, and that it could be more comfortable for them than pooing while floating on the sea surface.

The frequency and volume of defecation also interested the researchers, with the streaked shearwaters pooing every four to 10 minutes while airborne, and releasing an estimated 30g of faeces every hour – about five per cent of their body mass.

“We don’t know why they keep this excretion rhythm, but there must be a reason,” Dr Uesaka said.

Dr Uesaka intends to continue his research by using cameras with longer battery life and GPS to study where seabirds defecate further out at sea.

“Faeces are important but people don’t really think about it,” he said.

He hopes further research will reveal more about the importance of seabird droppings in distributing vital nutrients throughout ocean ecosystems.

A professional hazard

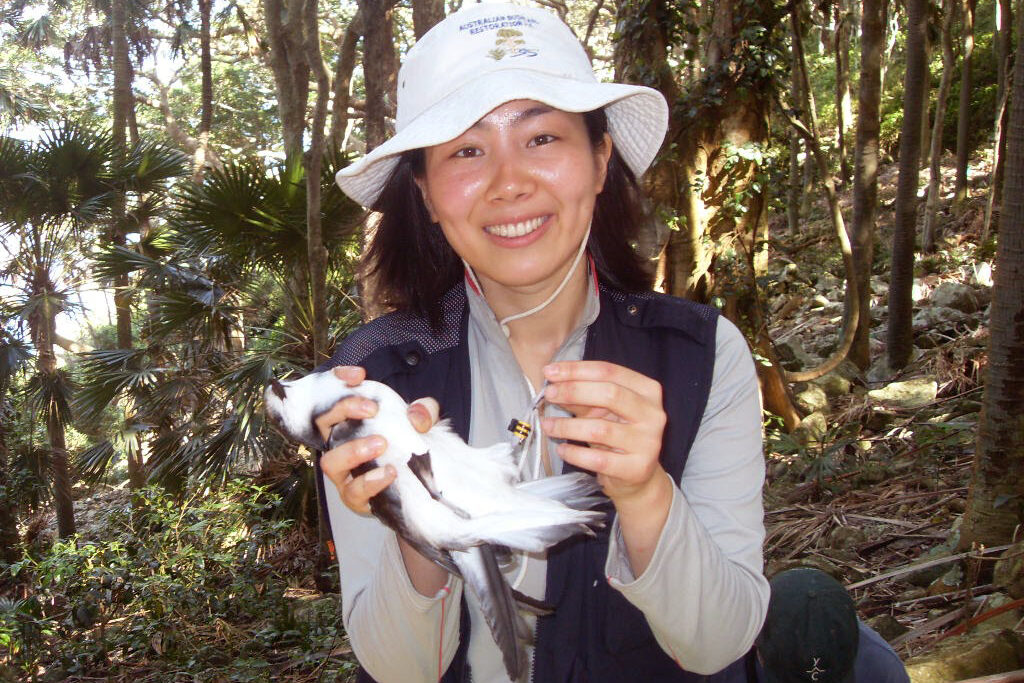

BirdLife Australia’s Seabird Project Coordinator, Dr Yuna Kim, told Australian Geographic that “flying bird poo” is a professional hazard for seabird researchers.

“I have spent quite a bit of time at sea observing seabirds. And you don’t look up in the sky with your mouth open. You don’t want to accidentally swallow any bird poo!” Dr Kim said.

“Seabirds quickly digest fish and squid and other food, take what they need and excrete what’s unnecessary. Especially for flying birds it’s important that they do this process quickly and efficiently.

“Shearwaters, for example, are very long-distance migratory birds, so for flying they need a light body. That’s why they need to poop so much.”

Dr Kim added that while her own research is not specifically focused on seabird droppings, further close encounters with bird poo at sea and on land are inevitable.

“We get covered by seabird poo out in the field, but we still love them!”

A vital resource

Dr Kim said that as well as being a fascinating – and yes, amusing – insight into seabird behaviour, the new study adds to a growing body of research into the importance of seabird faeces for coastal and marine environments.

“Poo is a really important source of nutrients. Poo in the ocean will feed plankton and other small fish, and when seabirds poo on land that guano is very precious,” Dr Kim said.

Seabird droppings are high in nitrogen and phosphorus, and research has shown some plant species are dependent on seabird faeces and that bird poo can even increase coral growth rates at remote reefs.

“Islands in particular are very isolated environments. Without seabirds their nutritional cycle will stop. It’s all connected,” Dr Kim said.