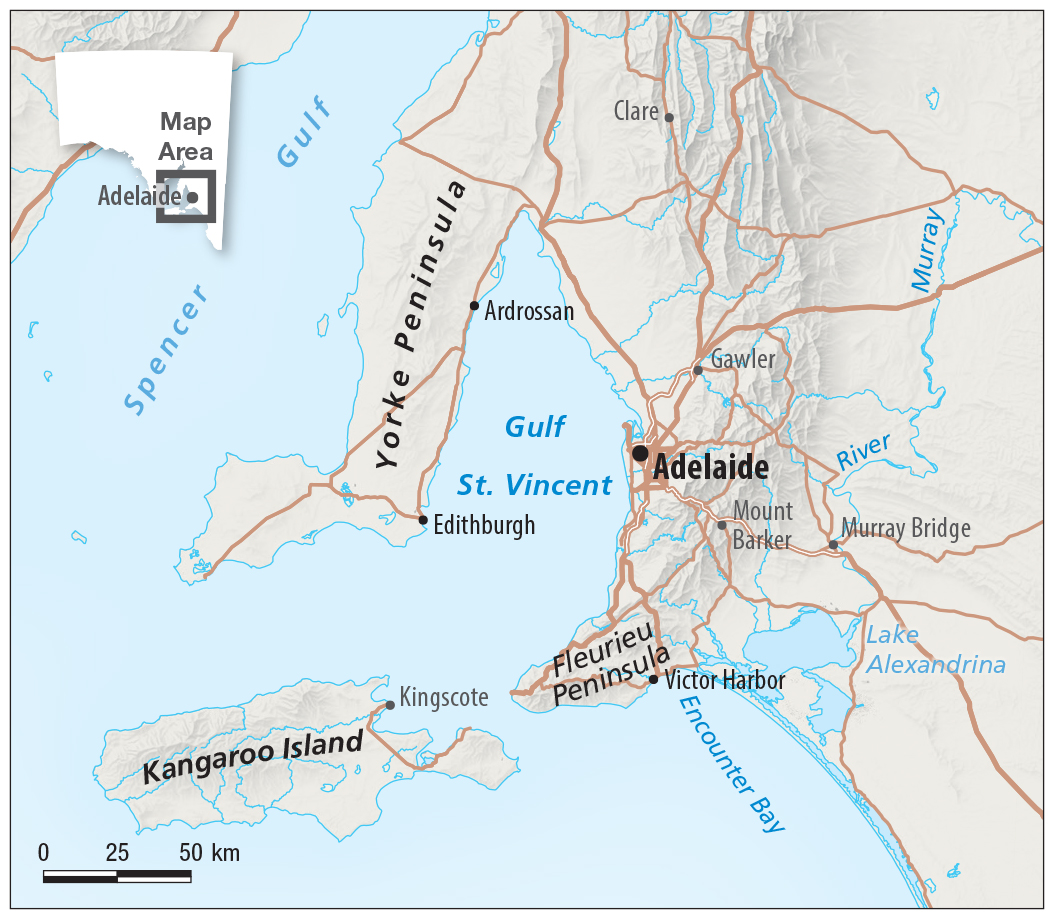

It has been a catastrophe unlike anything seen before in the Southern Hemisphere: since early autumn this year, the largest and most deadly bloom of marine algae ever recorded in Australian waters has been wreaking havoc across more than 4500 sq.km of coastal South Australia. First detected in March along Encounter Bay, almost 90km south of Adelaide, the bloom spread rapidly – first to the Yorke Peninsula and Kangaroo Island, then the Port River system, Adelaide’s beaches and the Fleurieu Peninsula. That’s an area twice the size of the ACT, and, at the time of writing, the bloom was continuing to grow and spread.

The devastation left by this unprecedented algal bloom has been vast, killing everything in its wake – from habitat-forming invertebrate species such as mussels and sponges through to megafauna like sharks, rays and dolphins. Entire food webs have been collapsing, the bloom transforming dynamic, colourful and highly productive ecosystems into what divers have been calling “underwater Armageddons”.

“It’s like diving into a graveyard,” says local SA diver Josh Dostal, who captured before-and-after photos of Edithburgh Jetty, on the south-eastern tip of the Yorke Peninsula, often described as SA’s best dive site. “What was once a bustling [marine] ‘city’ of colour and life is now silent, grey and lifeless.”

The bloom has been fuelled by marine microalgae – tiny plant-like organisms that are usually considered essential to life in the ocean. These sit at the base of most marine food chains and produce much of the oxygen we humans breathe. Most are harmless, even essential. But when conditions tip in their favour, some species can explode in numbers and become silent killers, turning the surrounding water deadly as they fill it with poisonous metabolic byproducts.

The recent SA blooms have been attributed to a complex mix of several different algal species, but the main culprit is Karenia mikimotoi. It’s an organism capable of producing harmful toxins that can clog the gills of fish, producing an immune reaction and breaking down gill tissue, effectively suffocating them. In large numbers, these microscopic algae also block light, deplete oxygen and produce harmful toxins, transforming thriving reefs into biological dead zones.

Three factors to blame

The recent SA bloom has been described by scientists as a ‘perfect storm’ driven by three factors occurring at the same time. One is a persistent marine heatwave affecting SA waters since September 2024, during which sea surface temperatures have been up to 2.5°C above average in many areas. Then there have been calm sea conditions with minimal tidal mixing. And, thirdly, coastal environments have been exposed to an influx of nutrients from summer upwelling, stormwater, agricultural runoff and the legacy of major flood events such as the 2023 Murray River flood pouring polluted freshwater into SA’s upper south-east.

These conditions have combined to act like a supercharged fertiliser. Warm water accelerates algal growth. Calm seas and light winds stop it from dispersing. And dissolved carbon from dead seagrass and seaweed caused by marine heatwaves fuel its spread. Once established, Karenia mikimotoi thrives. “It can swim to access deeper nutrients, survive across temperatures, and even feed on the marine life it kills,” explains Professor Perran Cook, a Monash University biogeochemist. “It’s like a bushfire in slow motion, underwater and invisible, sucking oxygen from the sea, releasing toxins and then feeding on the carnage: a hideous, self-perpetuating cycle.”

Image credits: Josh Dostal

More than 14,500 dead marine animals have been recorded by citizen scientists, spanning more than 450 different species, from SA’s iconic leafy seadragons and giant cuttlefish to countless other fish and invertebrates. “Even highly mobile species like rays, sharks and dolphins are being affected. This isn’t just a localised event; it’s an ecological catastrophe. Entire food chains are collapsing,” says marine ecologist Janine Baker, who co-manages the SA Marine Mortality Events project on iNaturalist, a global platform that empowers citizens to contribute biodiversity to real-time science and conservation.

Big blow to fishing and tourism

The economic fallout is equally dire. Michael Pennington, a second-generation commercial fisherman from the Yorke Peninsula town of Ardrossan, hasn’t worked in six weeks. “This time of year we’d usually see around 8–10 tonnes of calamari caught commercially in Gulf St Vincent. In July that dropped to 11–12kg across all commercial licences combined.”

Michael’s own monthly catch, which usually averages 500kg per season, is now at zero. Because squid usually spawn and lay eggs from July till the end of August, he fears there will be no stock for future years. “It’s unprecedented and disturbing,” he says. Michael isn’t alone, with many more holders of commercial fishing licences doing it tough, as huge quantities of dead garfish wash up on beaches.

Tourism has also taken a hit. Operators have been reporting cancellations and dive tours have had to be suspended. The catastrophe has also reportedly been directly impacting human health: beachgoers have reported headaches and breathing issues after swimming in affected waters.

Dr Scott Bennett, a marine ecologist at the University of Tasmania and co-founder of the Great Southern Reef Foundation, was among the first to survey more than 15 sites across Yorke Peninsula and Victor Harbor. What he and his team found confirmed the worst. “The destruction was visceral,” Dr Scott Bennett says. “Even habitat-forming species like sponges, bryozoans and ascidians were noticeably absent in the areas we surveyed. These organisms are vital to reef health, and while many typically dominate deeper waters beyond our current survey range, that only adds to our concern – the full extent of the damage to these foundational habitats remains unknown.”

Scott warns this isn’t a freak event. “All the ingredients are there for this to occur elsewhere,” he explains. “Climate change is intensifying marine heatwaves, and with that we’ll see more of these compounding events – algal blooms and the spread of destructive species like sea urchins, which overgraze and collapse productive kelp forests.”

And, in many ways, we are there now. Globally, extreme marine events are already becoming alarmingly common. Karenia blooms have for decades been causing mass die-offs across the world including in Japan, China, Norway, Ireland and the United States. In 2011, a marine heatwave wiped out kelp forests along 150km of Western Australia’s coast. And in 2015–16, Tasmania suffered major aquaculture losses and disease outbreaks linked to warming seas.

And, of course, it’s marine heatwaves that have underpinned the mass coral bleaching events that have been seen with increasing frequency on the Great Barrier Reef and more recently on Ningaloo reef.

Despite the scale of the unfolding disaster in SA, there had been, at the writing, no national emergency declaration. Dr Phillipa McCormack, from The University of Adelaide, says the legal framework does allow for one. “The floods in Lismore and southern Queensland were declared national emergencies. This bloom meets that same threshold,” she says. Current disaster frameworks, however, are built for fast-onset events such as floods and fires, not slow-building crises like marine heatwaves or algal blooms. That, she argues, must change.

In June, more than 80 marine scientists from across Australia and New Zealand met to assess the crisis. Their message: the need for a national marine monitoring system, early-warning tools and cross-sector collaboration to prepare for, and recover from, these events.

Scott remains hopeful. “The reefs aren’t completely dead. In some areas there’s still life, and marine ecosystems are incredibly resilient when given a chance,” he says, pointing to past seagrass and kelp recoveries in Adelaide and successful shellfish reef restoration as proof. “When industry and government work together, we can turn things around.”

On the frontlines of this unfolding crisis, everyday people – divers, fishers and coastal residents – are not only witnesses but also first responders. “For months we’ve been seeing incredible work coming out of small coastal communities on Yorke Peninsula, Kangaroo Island and Encounter Bay,” Janine says, adding that more than 700 people across SA have contributed to the dataset being used by marine NGOs, local communities, government agencies, university research scientists, journalists and others to help understand many of the visible impacts of the bloom over space and time. “Without these grassroots observations, much of the devastation would go unrecorded. These people are the eyes and ears of the ocean.”

‘Our underwater Black Summer’

During the summer of 2019–20, bushfires scorched more than 5 million hectares across eastern Australia, and towns such as Port Macquarie became global symbols of climate trauma. Emergency taskforces were mobilised. Donations poured in. The world watched.

“This is our underwater Black Summer,” Scott says. “Just like the bushfires that gripped the nation in 2019–20, it demands the same urgency, the same scale of response, and the same national reckoning.”

Scott is just one of many researchers arguing that the algal Armageddon that has been hitting the SA coast this autumn and winter has been just as catastrophic – although not as obvious because it has been raging mostly beneath the ocean surface. If thousands of animals were dying like this in forests, they claim, it would have quickly and officially been assigned national emergency status. Yet, at the time of writing there had been no national taskforce created and no emergency declaration – just exhausted researchers, grieving communities and hordes of citizen scientists trying to count bodies washing up with the tide.

Eventually, in late July, following months of mounting concern and advocacy, the South Australian Government matched a $14 million pledge by the Commonwealth, launching a $28 million package to support research, clean-ups, industry recovery and public awareness. It was a vital first step but widely seen as simply the beginning, not the end, of the coordinated national response that many believe is necessary.

The Great Southern Reef is one of Australia’s richest, but also arguably one of our most overlooked, marine ecosystems. And it has been hit hard by this catastrophe. Its vast kelp forests and seagrass meadows store carbon, support iconic species found nowhere else on earth, and sustain thousands of livelihoods across tourism, fisheries and aquaculture, forming the backbone of many coastal communities. Yet despite its immense ecological and economic value, it remains chronically underfunded and largely unmonitored.

Researchers have been ringing alarm bells for years about the collapse of this critical reef system, but with this latest catastrophe, there’s widespread concern that it has reached its tipping point.

For more information and to stay up to date, visit greatsouthernreef.com