Deep in the remote Tanzanian forest, immersed amongst watchful wild chimpanzees, a 26-year-old British woman with no science qualifications named Jane Goodall witnessed something that changed our perception of wild animals forever.

In doing so, Goodall, who has died aged 91 during a speaking tour in the United States, unleashed a storm of controversy. Her findings – that chimpanzees made and used tools – published in the journal Nature in 1964, challenged everything that science understood about the unique nature of humans and their relationship to animals. One day in 1960, while encamped on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, Goodall watched as a dominant male chimpanzee she had named David Greybeard thrust a stalk of long grass into an ant mound, then pulled it out and sucked the skewer clean of plump insects.

Soon after, Goodall witnessed David Greybeard, and another chimpanzee she named Goliath, stripping leaves off twigs to create the stalks they needed. This purposeful modification of an object was an astonishing demonstration of the first phase of toolmaking – a skill until then believed only possessed by humans.

“It didn’t surprise me that they used tools; it was exciting because I knew they weren’t supposed to,” Goodall told Australian Geographic in 2014.

“I’d seen how amazing chimpanzees are – and why would they be different in the wild? If anything, they might be thought to be more clever,” she said.

Goodall’s further observations, made from her camp, continued to defy universal beliefs about animal behaviour. Not only did the chimpanzees make and use tools, but they were occasionally carnivorous, hunting and eating the meat of bush pigs, small mammals and colobus monkeys. In behaviours remarkably akin to those of humans – reflecting a common ancestor – Goodall noted the chimpanzees’ capacity for compassion and for building and maintaining relationships, as well as their aptitude for violent warfare, traits that had never previously been attributed to animals other than humans.

“My observations at Gombe would challenge human uniqueness and whenever that happens, there is always a violent uproar,” she explained in the 2017 documentary Jane.

The story of Jane Goodall’s work with chimpanzees began in 1957, with an invitation from a schoolfriend to visit Kenya. Once there, she met renowned paleoanthropologist Dr Louis Leakey, who was looking for someone unconstrained by a science background to conduct great ape research. Leakey was trying to better understand human evolution and Goodall’s earnest passion for animals and sense of adventure rendered her ideal.

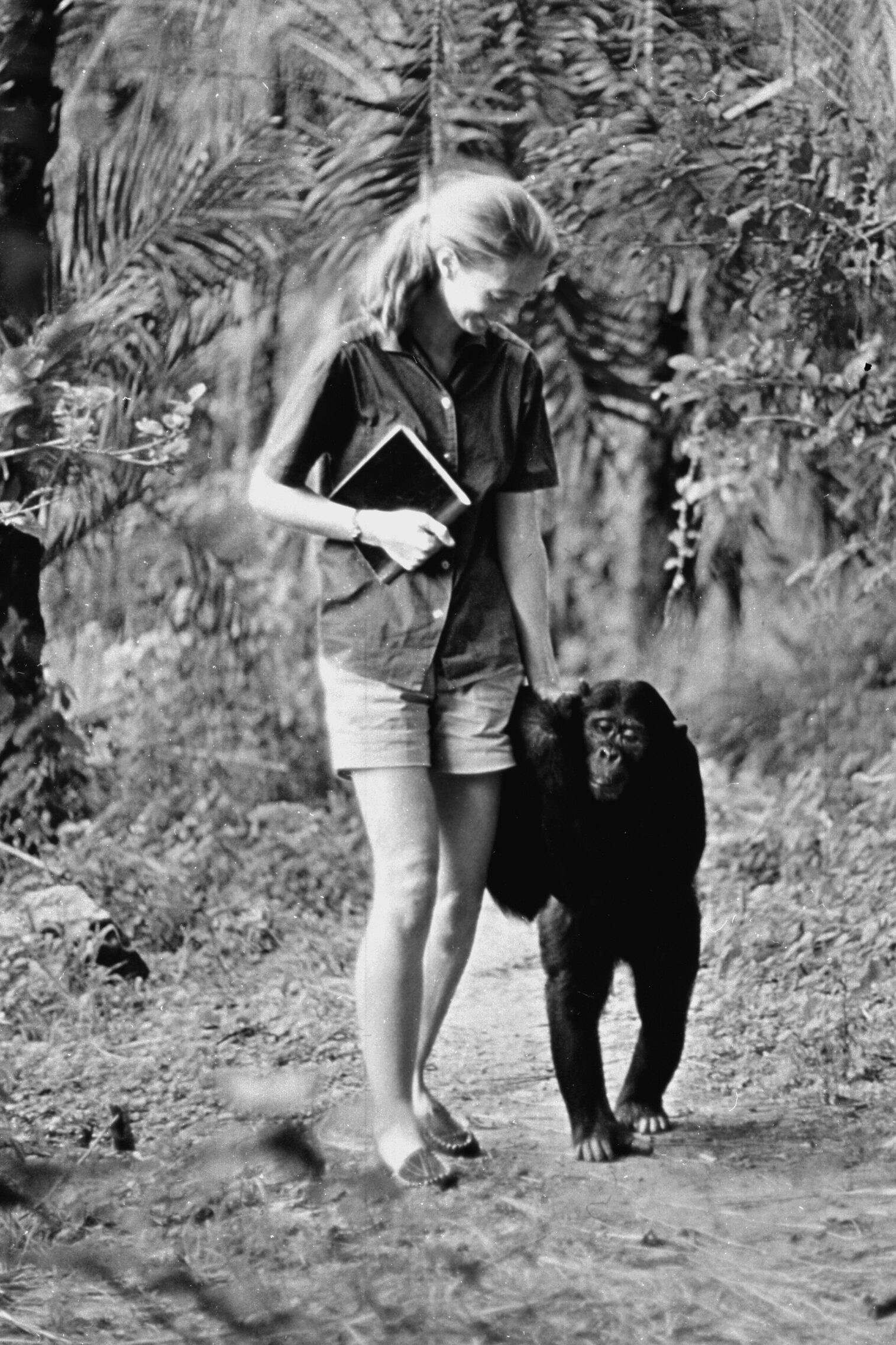

Often barefoot, and armed with a pair of binoculars, a notebook and endless patience and curiosity, Goodall spent months in what later became Gombe Stream National Park, building the trust of approximately 150 chimpanzees. Because it was believed to be too dangerous for a woman to live alone in the rainforest, she was initially chaperoned by a local cook and by her mother, who ran a health clinic for the local people while Goodall immersed herself among her study group.

It was the beginning of what has become the world’s most enduring and robust wild chimpanzee study.

Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall was born in London on 3 April 1934, the eldest of two daughters of Mortimer Morris-Goodall, a racing-car driver, and Margaret Joseph, known as Vanne. Her father’s frequent absence from her life was countered by her mother’s enthusiastic support of her interest in animals. Jane played with Jubilee, her stuffed toy chimpanzee, or with her dog Rusty, and, displaying an early aptitude for research, once put earthworms in her bed to study how they moved. At four years of age, she hid in their henhouse for hours, waiting for a chicken to lay an egg. Stories of Dr Doolittle and Tarzan inspired Jane early on to set her sights on living among animals in Africa and writing books about them. When the invitation to travel there presented itself, Goodall took waitressing and secretarial jobs and saved for two years to pay her passage aboard the SS Kenya Castle.

As she gained fame and notoriety for her pioneering work with chimpanzees, Goodall found herself in the glare of the world’s media who labelled her “pert” and “luminous, swan-necked, golden-haired” under headlines such as “Beauty and her beasts”. She ignored these, focusing instead on channelling publicity towards funding the Gombe Stream Research Center, which continues to host primate researchers from around the world.

Not only did Goodall’s astonishing discovery provoke uproar in the science world, but her research style was also considered controversial. Rather than numbering her subjects – as science mandated – she gave them names. To her observation, chimpanzees had distinct personalities, complex minds and emotional intelligence. But experts were appalled, arguing that Goodall must be contriving personas for the animals.

With Leakey’s support, in 1962 and with no undergraduate degree, Goodall was accepted by Cambridge University to study for a PhD in ethology, which she received in 1966. However, she found herself at loggerheads with researchers over her methods, with some suggesting she had taught the chimpanzees their behaviours.

“When I got to Cambridge, I was told I’d done everything all wrong and, you know, that I couldn’t…that animals couldn’t, or I couldn’t talk about animal personality, mind or feeling. I don’t think anybody believed it,” she said in 2014.

“I’ve had animals all my life. They all had names, even the snails that we used to race – they had names – so why on earth wouldn’t I name the chimps?”

From research to grassroots activism

Alarming deforestation leading to a decline in chimpanzee numbers during the 1980s prompted Goodall to reassess her role, pivoting from research to conservation and activism. Prior to COVID, she travelled 300 days of the year, sharing her message of hope and communal action. The eponymous institute she founded in 1977 continues its work as a global community-centred conservation organisation, with a focus on restoring critical chimpanzee habitat, supporting research, educating girls and improving health outcomes for those communities living alongside chimpanzees.

In 1991, prompted by the words, “If you don’t know about it, you don’t care about it”, Goodall established an environmental education program for children – Roots and Shoots – that operates across 100 countries.

While naming primates is now more mainstream, other practices once utilised by Goodall in her early research, such as handling or interacting with the chimpanzees, are no longer endorsed by the Jane Goodall Institute.

“We would never do it now. There was absolutely no knowledge back then that chimpanzees could catch human infectious diseases,” she said in a 2017 interview.

In 1962, and against Goodall’s wishes for privacy, National Geographic sent wildlife photographer (and Dutch nobleman) Baron Hugo van Lawick to Gombe to record her work. The pair fell in love and in 1964 were married. Their son Hugo, nicknamed Grub, was born in 1967. Following her divorce from van Lawick, Goodall married Tanzania’s national parks director Derek Bryceson in 1975; he died just five years later.

Goodall’s decades researching, writing and living among chimpanzees led not only to transformations in the study of animal behaviours, but saw her forge new pathways for women in science. As an activist, she unwittingly became the first iteration of the modern pop-culture science communicator, her charisma and fame ensuring her message of hope and community action was heard. She was immortalised by Lego and as a Barbie doll, and was the subject of a controversial cartoon by Gary Larson that became a fundraising t-shirt. Several documentaries were made, including Jane, which featured previously lost footage from Gombe, shot by her first husband.

“As I was travelling, I was meeting young people who seemed to have lost hope [about the climate crisis] and I thought, yes, we have compromised your future, we’ve been stealing your future. But it’s not too late for you to do something,” she said when selected as a featured ‘badass woman’ by InStyle magazine in 2020.

Goodall was named a Dame of the British Empire in 2004 and she was awarded the Legion of Honour in 2006. The United Nations named her a Messenger of Peace in 2002, and she was the recipient of multiple prestigious awards, honouring her contribution to science and the environment.