In the icy waters of the Southern Ocean, 19th- and early 20th-century mariners reported fleeting glimpses of what appeared to be land – shadowy shapes on the horizon and nebulous silhouettes shrouded in fog. These sightings were diligently marked on nautical charts and, for a time, accepted as genuine discoveries. Yet these “discoveries” were nothing more than illusions. They never truly existed.

The origins of such phantom islands were surprisingly varied. Some may have been real landmasses that later eroded or sank beneath the waves. More often, they were honest mistakes: icebergs misidentified as land, atmospheric mirages, or navigators miscalculating longitudes in challenging conditions. In a few rare cases, they were deliberate fabrications by captains eager to impress sponsors or secure funding for further voyages.

By the late 1800s, reports of phantom islands had grown to an astonishing level, with hundreds of them littering nautical charts. Accordingly, the British and United States Hydrographic Offices began systematic efforts to verify such reports and remove any doubtful islands from official records. Yet many remained in circulation for decades, a reflection of how difficult such errors were to rectify.

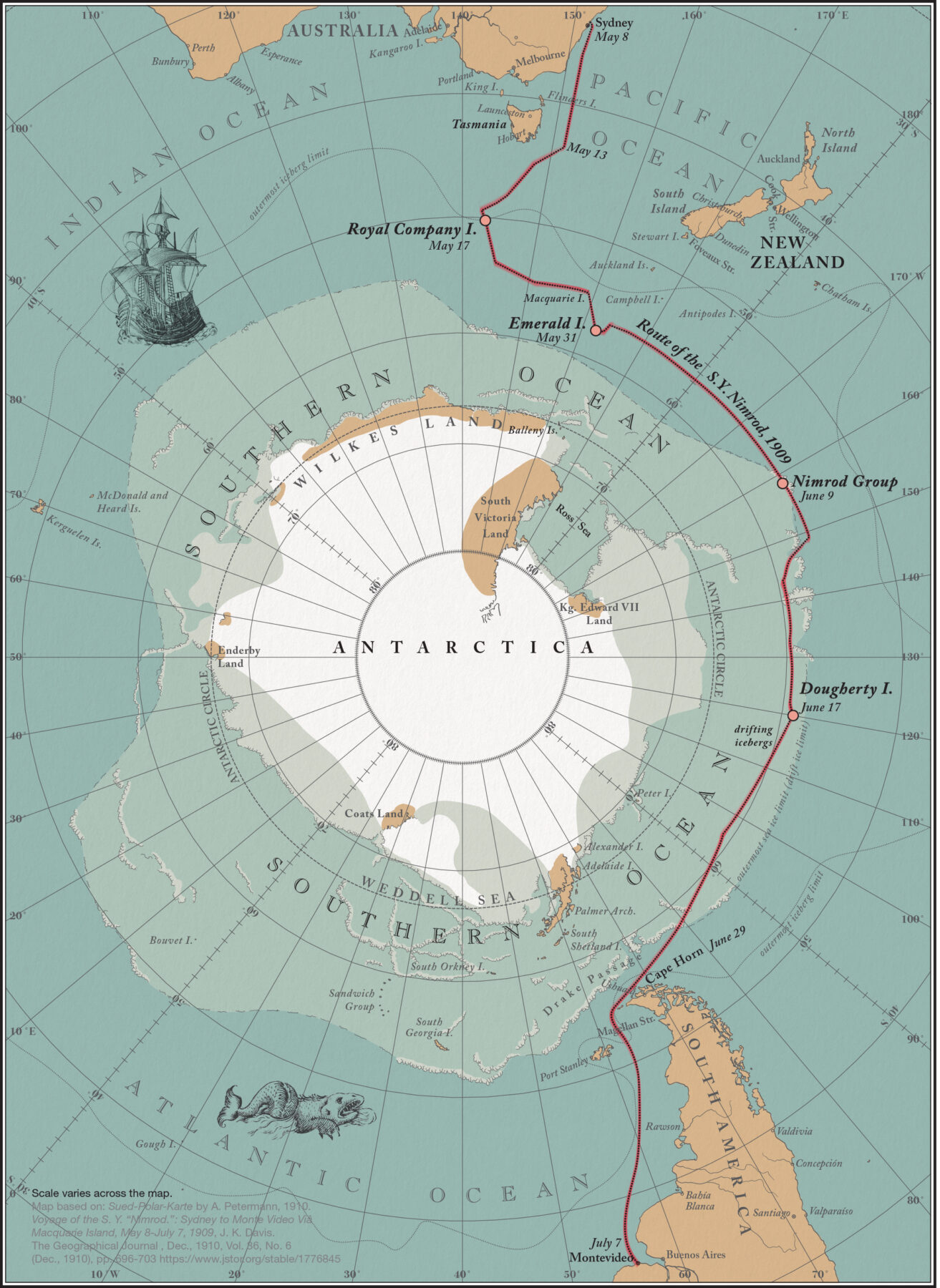

Among the most enduring of the Southern Ocean phantoms were Emerald Island, the Nimrod Islands, the Royal Company Islands, and Dougherty Island. Despite repeated and often arduous failed attempts to locate them, their names stubbornly remained on charts for generations. The stories behind each reveal how the lure of discovery, coupled with the uncertainties of early navigation, could transform a fleeting sighting into an accepted geographical fact.

Lingering ghosts

The most persistent phantom was Emerald Island (57°30’S, 162°12’E). It’s perhaps the clearest example of how a single uncertain sighting could evolve into an accepted geographic feature, remaining on maps for more than a century. Its story began in 1821, when Captain Elliot of the British vessel Emerald reported that “we saw the semblance of an island bearing east by north”, some 25 miles away, about 30 miles long with high-peaked mountains. The sighting sparked enough interest to warrant inclusion on nautical charts, yet no landing was attempted, and no further observations were recorded.

Despite the vagueness and lack of verification, Emerald Island soon appeared on British Admiralty charts. The allure of discovery was powerful: early editions depicted it with a clear outline, while later versions prudently added a question mark. Yet its cartographic life endured. For decades, ships bound for the Antarctic were advised to watch for it, and sealers and whalers speculated about its untapped resources. So persuasive was belief in its existence that the US Exploring Expedition under Lieutenant Charles Wilkes designated it as a rendezvous point for his fleet in January 1841. Wilkes, however, found nothing but open sea.

Still, the phantom proved remarkably resilient. On 31 May 1909, Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Nimrod Expedition specifically navigated over Emerald Island’s supposed position, confirming its absence with deep-sea soundings. About 30 years later, in 1936, the British Royal Research Ship Discovery II passed within a few miles of the same area and took a sounding of 2595 fathoms (about 4745m), confirming it was far too deep for any island. Yet, despite repeated failed sightings and conclusive soundings, Emerald Island continued to appear on some charts and in atlases until the 1970s.

East of the persistent Emerald Island lay another phantom, sometimes appearing on charts as a small cluster known as the Nimrod Islands (56°30’S, 158°30’W). Their entry into cartographic history began in 1828. It was then that Captain Eilbeck of the Nimrod, on a voyage from Port Jackson around Cape Horn, reported several low-lying islands with numerous seabirds and marine vegetation. This vivid description of life in the desolate Southern Ocean lent credibility to his account. Perhaps the prospect of discovering new land – especially apparently rich in resources, as the abundant marine life suggested – may have been compelling enough for these unverified islands to be swiftly added to charts.

However, these recorded illusions were soon put to the test. In 1831, the seasoned explorer John Biscoe, sailing for the Enderby Brothers of London aboard the brig Tula, searched for the Nimrod Islands during his return voyage to Hobart. He noted a submerged bank but could not confirm whether it was an island. Nearly 80 years later, on 9 June 1909, Shackleton’s Nimrod Expedition crossed the reported position on a clear night without sighting anything. Yet the islands remained on Admiralty charts until 1936.

Cartographic enigmas

South of Macquarie Island, a group known as the Royal Company Islands (approx. 50°25’S, 143°E) was another tenacious charted illusion. This phantom group appeared on numerous 19th-century charts and stubbornly remained in nautical references for decades. Its uncertain origin is often attributed to a sighting in 1776 by the Spanish ship Rafaelo of the Royal Company of the Philippines. The original reported position was about 49°S, 143°E, some 420 miles south of Tasmania – a remote and treacherous expanse where navigation was crucial, albeit unreliable.

Between 1820 and 1870, these islands remained a cartographic enigma. Their charted positions frequently shifted between 49°S and 53°30’S and 141°E to 145°E. Whether these movements reflected conflicting reports or cartographers simply relocating the name after failed sightings remains unclear, a testament to the deepening ambiguity surrounding them. Although some mapmakers left the islands off entirely – reflecting growing scepticism – others continued to chart them, choosing caution over certainty.

Still, efforts to locate them yielded nothing. In January 1840, French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville sailed directly to their reported location and noted, “Notwithstanding careful searching and a most favourable horizon, we saw no land.” Later that year, Wilkes’s US Exploring Expedition also searched the area, with the same result. And on 17 May 1909, Shackleton’s Nimrod Expedition passed over the supposed site, taking a sounding of 2430 fathoms (about 4444m) – definitively proving the islands did not exist and prompting their removal from Admiralty charts.

The last of the great Southern Ocean phantoms to be charted was Dougherty Island (59°S, 120°W), believed to lie roughly halfway between Chile’s Cape Horn and New Zealand. Its existence was first reported on 29 May 1841, by Captain Dougherty of the whaler James Stewart. His initial description was remarkably detailed for what ultimately proved to be an illusion: an island 5–6 miles long, aligned north-east to south-west, with a high bluff at the north-eastern end, a snow-filled valley at the centre, and low land at its south-western point. Such specifics, rather than fleeting glimpses, quickly fuelled the belief in this remote discovery.

In 1859, a second confirmation came from Captain Keates of the Louise. He not only confirmed its existence but added further specific observations describing a dark, round island, about 80ft high, with an iceberg aground on its north-west side. Confident in his position and chronometer, Keates gave precise coordinates: 59°20’S, 119°7’W. The island’s reality appeared increasingly plausible. Adding to the island’s cartographic persistence, officer Stannard of the barque Cingalese later claimed two sightings, in 1886 and again in 1890. He reported to have spent three days near the island and described it as 6 miles long, 300 feet high at the north-east, and very rugged at the other end with no signs of vegetation. These repeated, detailed accounts helped embed Dougherty Island into accepted geography. Despite this accumulation of ‘evidence’, the uncertainties of accurate charting and the vastness of the Southern Ocean eventually led to its undoing.

Between 1894 and 1910, Captain Herbert Greenstreet of the New Zealand vessel Rimutaka crossed the supposed area four times in clear weather, each time finding only open sea. Most conclusively, in 1904, Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott passed through the region, and recorded a depth of more than 2318 fathoms (about 4240m). His direct observation and scientific measurement left no room for doubt: “Had there been an island within reasonable limits of its supposed position,” he famously remarked, “we could not have failed to see it.”

On 17 June 1909, Shackleton’s Nimrod Expedition encountered only two drifting icebergs near Dougherty Island’s reported coordinates, one of which may have inspired the original sightings. It was not, however, until the 1930s, when various research vessels made repeated soundings at the published location, that the island was finally expunged from the International Hydrographic Bureau’s official lists.

Shaping maritime history

Even though these phantom islands never truly existed, their elusive presence profoundly shaped maritime history; altering shipping routes, informing rendezvous plans, and even influencing rescue missions. Their remarkable endurance on charts reveals how the lure of discovery, hazards of navigation, and pull of the unknown could transform fleeting glimpses into, for a time, accepted geographical fact.

Ultimately, these phantom islands serve as a powerful reminder that cartography is never fully objective. It took the determined efforts of explorers to sail into uncertainty and prove that some of the Southern Ocean’s most enduring landmasses were, in the end, illusions.

Dr Catherine Akeroyd is a historian of cartography and editor of The Globe, the journal of the Australian and New Zealand Map Society (ANZMapS). The Society is holding its annual conference, Southern Frontiers, at MONA, Tasmania, on 17–18 October.