Hunters or collectors? New evidence challenges claim Australia’s First Peoples hunted megafauna to extinction

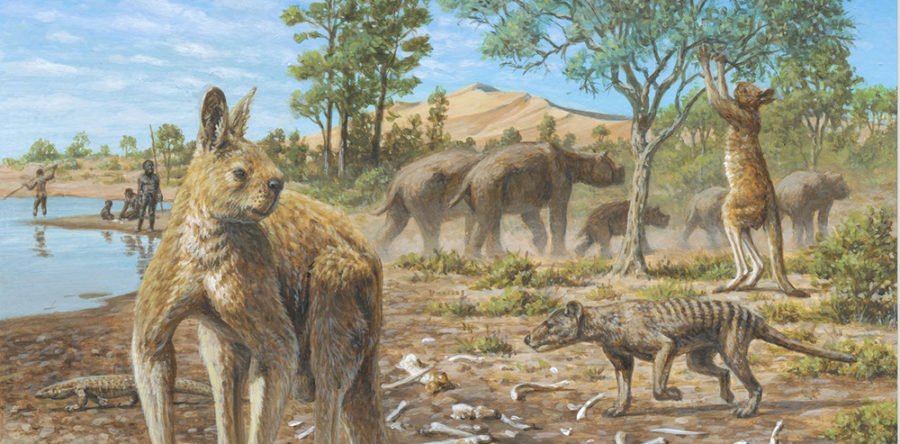

Tens of thousands of years ago, Australia was still home to enigmatic megafauna – large land animals such as giant marsupial wombats, flightless birds, and short-faced giant kangaroos known as sthenurines.

Then they gradually went extinct. What killed them?

There has long been vigorous debate about whether Australia’s First Peoples were responsible for the extinction of Australia’s megafaunal animals, or whether the primary cause was climate change.

In other places, such as the Americas, Aotearoa New Zealand and Madagascar, humans have been linked to such extinctions. This led some researchers to presume humans may also have hunted megafauna to extinction in Australia.

However, hard evidence for this has been hard to find. With new methods, we have re-examined fossil bones that seemingly supported this idea in the 1970s, and have arrived at a new conclusion. Our results are published today in Royal Society Open Science.

A long-standing debate

Humans appear to have first entered Australia during the late Pleistocene epoch perhaps 65,000 years ago. At the same time, Australia was also experiencing a fluctuating climate.

So, when much of the local megafauna went extinct tens of thousands of years ago, which factor was responsible? Debate rages on over whether it was human activity or climate change, or perhaps something else entirely.

Australia doesn’t have any “kill sites” or other incontrovertible hard evidence that people were killing and butchering the local megafauna. This is in contrast to sites found in North America, such as Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump World Heritage Site in Canada where people hunted vast numbers of buffalo.

So, in Australia, researchers have focused on individual fossils instead. Over time, most of the scant evidence for human involvement in megafaunal extinction has been discounted. Only a few notable finds remain.

The first is a single incisor from a giant marsupial Diprotodon optatum. The tooth was found in Spring Creek, Victoria, with a series of small cuts suggested to have been made by humans. Reappraisal now suggests tiger quolls may have been to blame.

A piece of a juvenile diprotodon bone, from the Warratyi Shelter in the Flinders Ranges of South Australia, has also been put forward as evidence for killing and butchering. However, a 2016 study argues the marks on the bone can’t be ascribed to human activity.

Burnt eggshell fragments found at several sites in Australia have been attributed to people predating on the giant Genyornis newtoni bird, although others argue the shell fragments were from a much smaller bird.

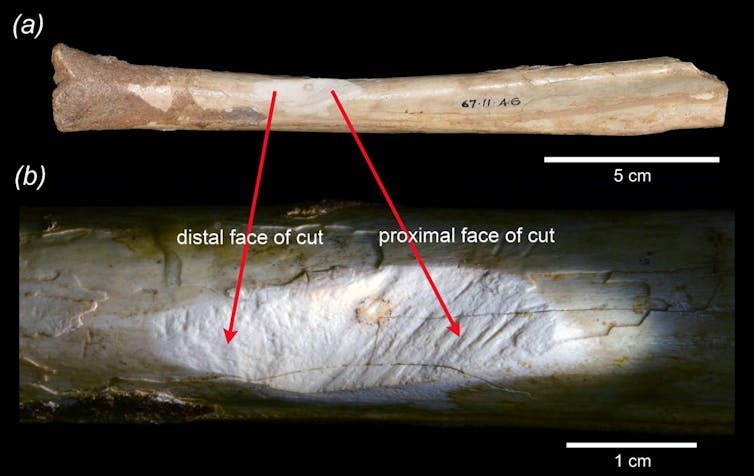

Finally, a cut bone from an extinct sthenurine kangaroo from Mammoth Cave in southwestern Western Australia has been suggested as evidence of human butchering. One of us, Mike Archer, co-authored that study in 1980.

Revisiting the past

With technologies not available in the 1970s, we sought to investigate the same bone from Mammoth Cave in more detail. Close analysis of the surface supported the original conclusion that the cut was indeed caused by human activity, not by animals or falling rocks.

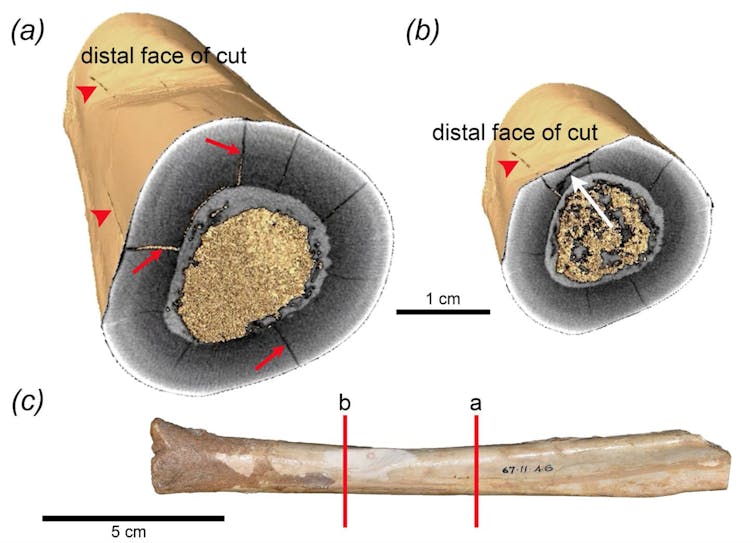

But a micro-CT scan revealed a surprise.

Internally, the bone has seven deep cracks running the length of the shaft. These happened due to taphonomic desiccation, a drying-out process that happens long after the animal has died.

Investigating the site of the cut, we found a separate transverse crack precisely in the base of the cut area. This had almost certainly been caused by pressure from the cutting process.

Importantly, the crack was truncated at both ends where it intersected the longer cracks. This means the bone would have already been desiccated when the cut was made.

In short, the bone was not from a fresh carcass when it was cut. In all probability, it was already a fossil.

Fossil gifts

This poses an even more intriguing question. Did the First Peoples who inflicted this cut collect this bone because it was an interesting fossil, rather than a source of nutrients?

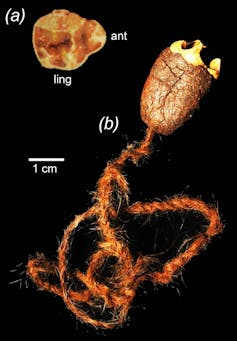

The idea led us to analyse an artefact containing a fossil that had been gifted by First Nations people. In the 1960s, local First Peoples in the Kimberley region of northern Western Australia gifted the late anthropologist Kim Akerman a “charm” containing the tooth of a giant extinct marsupial, Zygomaturus trilobus. He was also given an emu feather parcel with teeth which turned out to be from an extinct sthenurine kangaroo, Procoptodon browneorum.

These animals are only known from fossil deposits in southern Australia, far from where these items were gifted. When we analysed the elemental composition of the Z. trilobus tooth, we found it likely came from Mammoth Cave, 2,000 kilometres to the south.

Collectors, not hunters

First Nations people in Australia have long collected and traded various kinds of fossils like trilobites, ammonites and mammal jaws.

This interest in fossils may be the best explanation for the cut in the desiccated bone found in Mammoth Cave, and the fact that fossil teeth from thousands of kilometres away ended up in the Kimberley.

It may also explain the Diprotodon optatum bone found in the Warratyi Shelter deposit in the Flinders Ranges. There’s a conspicuous mass of skeletal remains of this megafaunal species exposed and available for collection on the surface of Lake Callabonna, a relatively short distance from the shelter.

Gerard Krefft and Ludwig Glauert are often cited as the first “Australian” palaeontologists. We would argue that First Nations peoples beat them to the punch, likely by many thousands of years.

There is currently no hard evidence that extinct megafaunal animals in Australia were butchered by First Peoples in Australia. That’s not to say it didn’t happen. However, despite many investigations, we still have no proof that it did.

About the authors: Mike Archer, Professor, Earth and Sustainability Science Research Centre, UNSW Sydney; Blake Dickson, Lecturer, School of Biomedical Sciences, UNSW Sydney; Helen Ryan, Collections Manager (Palaeontology), Western Australian Museum; Julien Louys, Professor, Palaeontology, Griffith University, and Kenny Travouillon, Curator of Mammals, Western Australian Museum

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.