Even with 112,000 people packed in, Stadium Australia was silent for just a moment on the evening of 25 September 2000. In Lane 6, sprinter Cathy Freeman – clad in her iconic green-and-gold full-body Nike Swift Suit – steadied herself on the starting blocks ahead of the biggest race of her life: the 400m Women’s Final. But her journey to this point had been about far more than sport.

Freeman – a Kuku-Yalanji and Birri-Gubba woman from Mackay, Queensland – had previously won 400m gold at the Commonwealth Games and the World Championships, but had yet to taste Olympic glory. At the Atlanta Games in 1996, she took home silver to French archrival Marie José Pérec, who ran an Olympic record 48.25 to Freeman’s 48.63. The pair were favourites again in Sydney, but this time the Aussie was looking to go one better. And this time, it would be on home soil.

Expectations among the Australian public were immense. Freeman was the ‘face of the Games’ – on 15 September she lit the Olympic flame in what was seen as a powerful national symbol of reconciliation with Indigenous Australians. The reconciliation movement was gathering momentum in Australia at the time after the 1997 Bringing Them Home report had laid bare the trauma of the Stolen Generations. In May that year, more than 250,000 people had walked across the Sydney Harbour Bridge in support of the movement. It was the largest single political march in Australian history.

After her wins in both the 200m and 400m Finals at the 1994 Commonwealth Games, Freeman carried the Aboriginal flag alongside the Australian flag on her victory laps. At the time, it caused a stir. Most high-profile was the response from Australian Commonwealth Games boss and chef de mission, Arthur Tunstall, who asserted that the Australian flag was the only flag any athlete should display, and even threatened to send Freeman home. Technically, the rules of the Commonwealth Games – and, indeed, the Olympic Games – mirrored Tunstall’s stance. Athletes were permitted only to use national flags in medal ceremonies and victory laps. Public sentiment, as ever, was mixed, but many supported the personal, unifying and symbolic nature of Freeman’s decision.

In the lead-up to the 400m Final in Sydney, these questions dominated the narrative. Could Freeman beat Pérec this time around? Could she handle the weight of expectation as the ‘poster girl’ of Sydney 2000 in front of an adoring home crowd? And if she won, would she carry both flags on her victory lap – and would she penalised by the IOC if she did?

The first question – that of her rivalry with Pérec – had an unexpected twist just days before competition was set to begin. The French sprinter had been noticeably reclusive since her arrival in Australia, refusing to train with the French team and hiding from reporters, which only intensified their focus. Then, 48 hours before the first heat, she left Australia in the middle of the night, withdrawing from the Games and, in turn, from defending her gold medal. To this day, the details of her departure remain cloudy. Pérec said she’d been harassed in her hotel and that she feared for her safety. Others suggested the hotel situation was overblown and that she simply wasn’t mentally ready to compete. Parochial local media flat out accused her of ducking the contest.

Either way, when Freeman lined up for the 400m Final in front of 112,000 fans, Pérec was nowhere to be seen. And the pressure for Freeman to win was now even more intense.

She paced the track with purpose ahead of the start, drawing the occasional long breath and closing her eyes. As she approached the starting blocks, she drew the distinctive green cap of her Swift Suit over her head. She took her mark.

The gun cracked, and Freeman took off. The crowd of 112,000 immediately found its voice. Her start was clean, and she rounded the curves strongly, but as she entered the home straight she was marginally behind Jamaica’s Lorraine Graham and Great Britain’s Katharine Merry. Then, she exploded. The decibel level of the fans rose with each stride as she pulled away from the field. She crossed the finish line comfortably in front, recording a time of 49.11 – not as fast as Atlanta without Pérec there to push her, but an Olympic gold medal winner nonetheless.

After the race, she celebrated inwardly before she celebrated outwardly – removing her hood, sitting down on the track, closing her eyes. Relief, she later said, was the overwhelming emotion. Then she rose, took out both flags, and began a slow lap of honour of Stadium Australia, a smile overcoming her as that relief turned to joy.

In the days and weeks that followed, dissenting voices were far more difficult to find than they had been six years earlier. Freeman’s decision to carry the Aboriginal flag alongside the Australian flag was widely embraced and became one of the defining images of the Games. Twenty-five years on, her run remains one of Australia’s most iconic sporting performances.

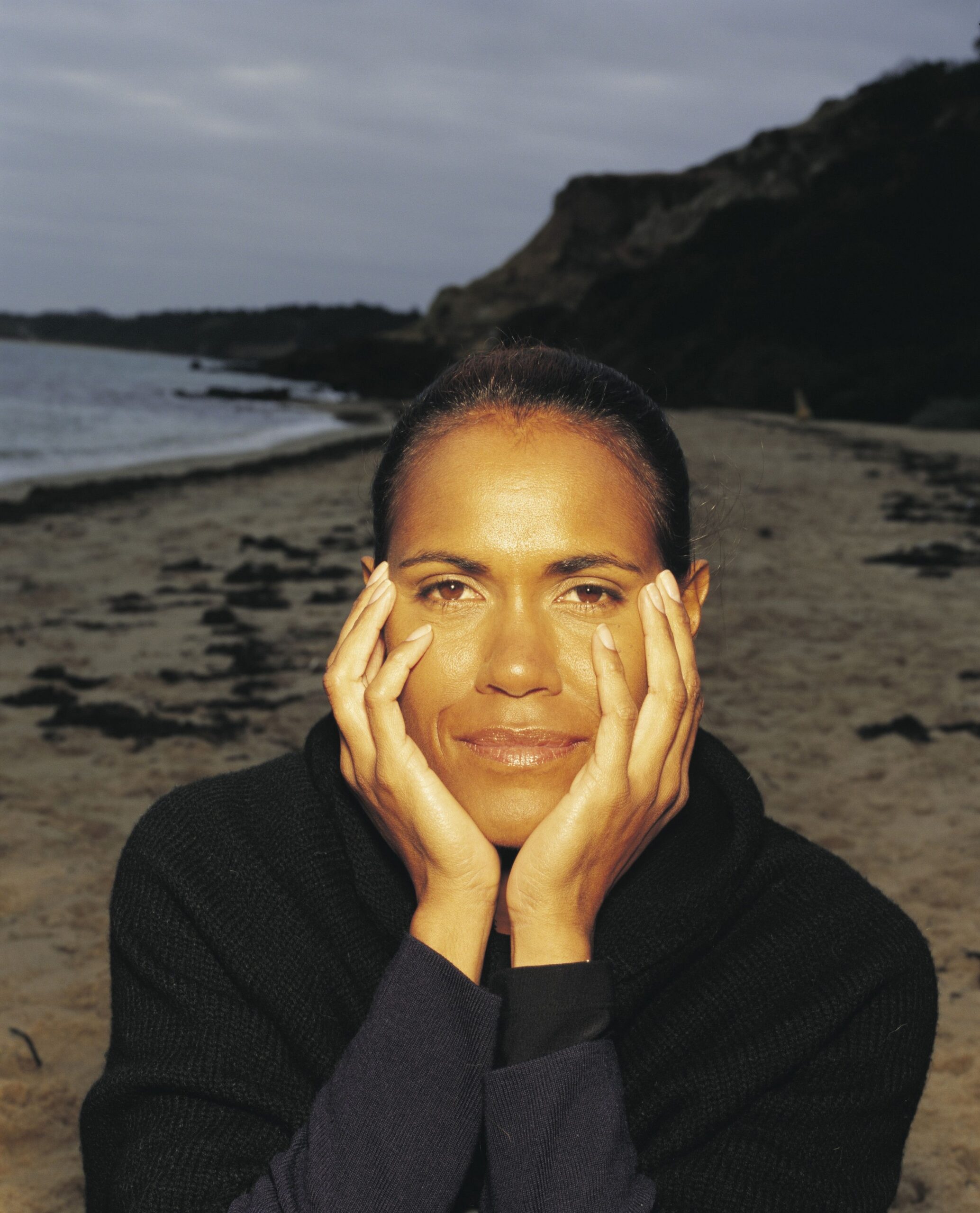

Cathy Freeman shuts her eyes and breathes in a crisp, salt-laden Port Phillip Bay breeze. She sits in cold yellow sand and hugs bent knees. “There’s always, always a sense of solitude here,” she sighs contentedly. “I just love it, it’s beautiful”.

Here is Black Rock beach, in Melbourne’s south-eastern suburbs. It’s where Cathy endured years of pain, training for that nation-stopping 2000 Sydney Olympic moment when her lithe form dashed around the track in the women’s 400 m final to claim a gold medal. It was the pinnacle of an exceptional career.

For Cathy, Black Rock was a serious workplace during the intense pre-Olympic period. But it was also a soft environment that provided regular and welcome respite from the hard lines of the track and gym, where elite athletes usually hone their skills.

“Training in a place like Black Rock actually enhanced my ultimate performance,” she says. “I trained very hard here, very hard. Now it’s a wonderful place for reflection, not just on my running career, but on everything.”

Cathy’s ancestors, on both parents’ sides, were coastal people, and probably had been for millennia. “A sense of connection to the land and spirituality with nature is something that’s just in my blood because of my Aboriginality”, she explains. “I love it when my senses are awakened like they are here. One of the things I miss most about Australia when I travel is our natural beauty.”

This is an excerpt from an article entitled My Australia, written by Karen McGhee – published in Australian Geographic magazine in 2006 – which explored significant Australians and their connection to place.

Image credit: Robin Sellick/Australian Geographic