No concrete evidence to support common Aussie myth

Did you hear the story about the workman who was buried alive in wet concrete during a bridge construction? Or was it a dam?

Did you hear the story about the workman who was buried alive in wet concrete during a bridge construction? Or was it a dam?

There’s something magical about a ray of sunlight, especially if it illuminates an object of reverence. Even more so if it’s a spectacle that only occurs once a year.

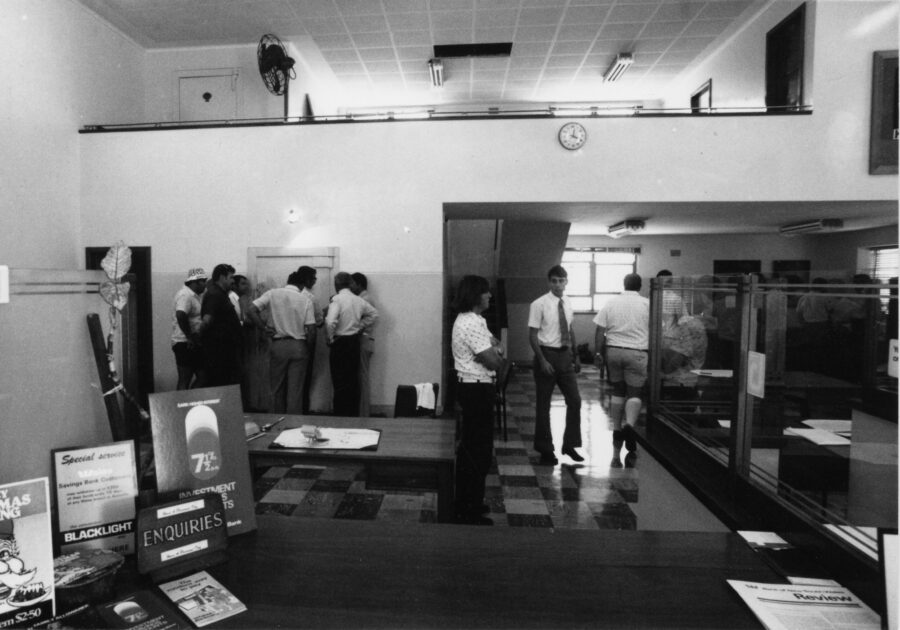

When residents of the NSW Northern Rivers town of Murwillumbah awoke on 23 November 1978, they discovered their main street was crawling with police cars and camera-toting media.

The claim that bats only fly left when exiting a cave is a common misconception.

Wycliffe Well is a tiny speck off the Stuart Highway in the middle of the Northern Territory, about 130km south of Tennant Creek. The former roadhouse was named after the site of a water well sunk in 1875 for workers on the Overland Telegraph Line.

The way ahead is blocked by an imposing jumble of jet-black boulders precariously stacked on each other. Beneath this is an eerie underworld of secret chambers where giant pythons and carnivorous ghost bats lurk.

When I first heard about the relic World War II tank traps hidden away in the forests of south-east New South Wales, I thought someone was pulling my leg. It was only after I discovered my informant was a rural firefighter who’d seen the timber obstacles marked on an old map, that I took the claims seriously.

Australia’s thousands of kilometres of rocky coastline and shallow reefs harbour the rusting relics of more than 8000 ships.

By definition, a final resting place is final, isn’t it? Well, not always, it seems.

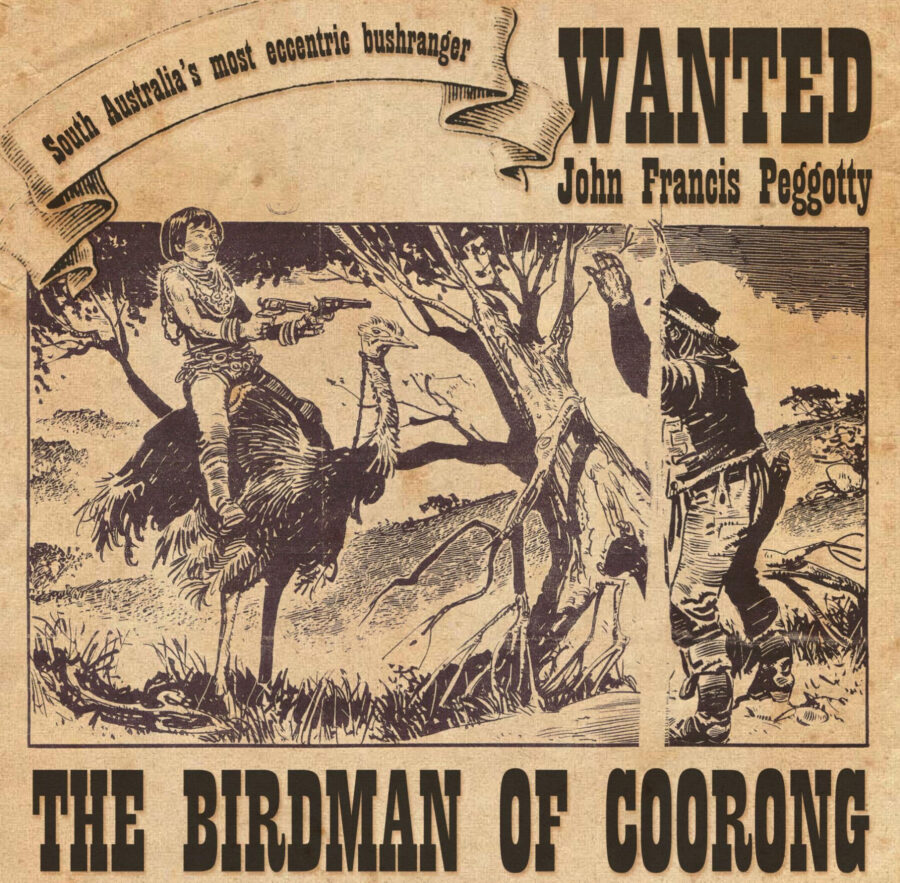

Ned Kelly, Ben Hall and Captain Thunderbolt – the criminal exploits of these notorious bushrangers are forever etched into our national psyche. But what about the Birdman of the Coorong?