Feelings of impending doom? That’s just the Irukandji jellyfish

Bec Crew

Bec Crew

Irukandji jellyfish are a type of box jellyfish primarily found in the tropical waters of northern Australia. Named after the Irukandji people of north Queensland, this jellyfish remained a mystery for decades.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that Cairns-based doctor Jack Barnes identified it, famously stinging himself – and a lifeguard and his nine-year-old son! – to prove its potency (all three survived).

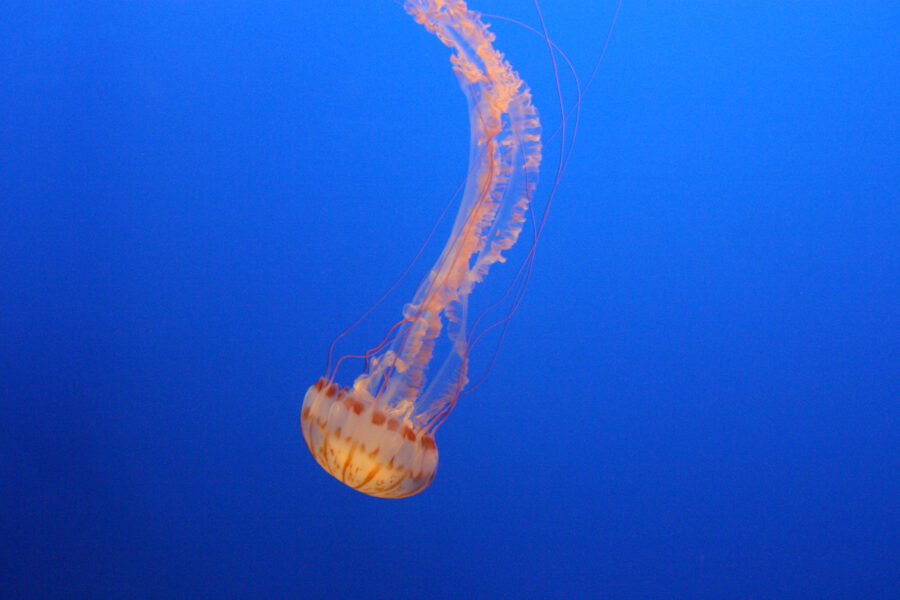

Image credit: shutterstock

The best-known species of Irukandji jellyfish (and the one that Dr Barnes identified) is Carukia barnesi, but many more have been recorded over the past few decades, including Morbakka fenneri, nicknamed the fire jelly, and Malo kingi, also known as the common kingslayer. Why is it called that, you may ask? Australian jellyfish expert Lisa-ann Gershwin named it in honour of Robert King, the second person in history confirmed to have died from Irukandji syndrome.

It’s not just the headache, anxiety, cramping and up to 12 hours of relentless vomiting that you have to worry about if you get stung by an Irukandji jellyfish. There’s also the “feeling of impending doom”, as researchers have described it.

“Patients believe they’re going to die and they’re so certain of it that they’ll actually beg their doctors to kill them just to get it over with,” Gershwin told ABC radio in 2007.

It isn’t clear what causes this feeling in Irukandji sufferers, but researchers think it could be related to how the venom causes an uptick in the hormones adrenaline and noradrenaline, which are connected to anxiety.

Victims of the Irukandji jellyfish can experience long-term effects such as nerve damage and psychological trauma.

What makes these creatures extra spooky is they’re extremely hard to see – their transparent, cube-shaped bell is barely the size of a fingernail. But their tentacles can extend a full metre when hunting. Irukandji jellies lurk in warm waters, waving their tentacles like lures to attract small fish.

When prey ventures too close, thousands of microscopic, venom-laced harpoons called nematocysts fire from their tentacles. Immediately incapacitated, the prey is pulled towards the jellyfish’s bell by retracting tentacles to be consumed.

Human injuries are extremely rare and accidental. But if you’re one of the unlucky ones and get an Irukandji (or any jellyfish) sting, don’t pee on it! It’s an urban legend.