Kiwi bird of NZ not an Aussie immigrant

John Pickrell

John Pickrell

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF the large flightless birds of our planet’s southern continents have always been very difficult to tease apart.

The bone structures of the emu and cassowary (Australia), the moa and kiwi (NZ), rhea and tinamous (South America) and the giant elephant bird (Madagascar) showed they were all related, but the links between species didn’t always seem to follow geography as you might expect.

The ‘palaeognath’ birds (or ratites, as most of them are known), are interesting for a number of reasons: they are the most ancient lineage of living birds and their ancestors were contemporaries of Southern Hemisphere dinosaurs in the Late Cretaceous period, more than 66 million years ago. They are also the only bird group to be made up largely of flightless giants.

Moa and elephant bird: extinct giants

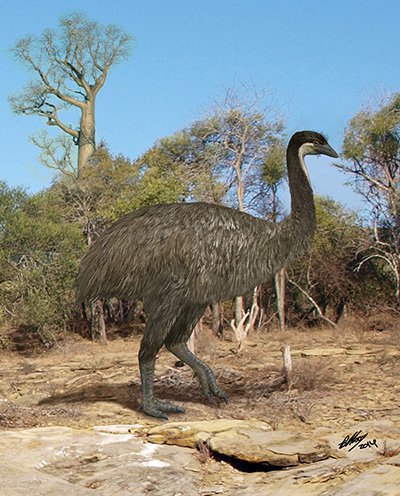

The two extinct groups – the Madagascan elephant birds (2-3m tall, 275kg weight) and the moa of New Zealand (2-3m tall, 250kg weight) – were the largest birds to survive into the modern era, and both were likely driven extinct by the arrival of humans on their respective islands.

Much to the consternation of New Zealanders, previous DNA work in the 1990s had suggested that the kiwi was a relative of the emu and cassowary. More recent fossil finds seemed to confirm the idea that NZ’s national bird had descended from a flight-capable ancestor that flew across the Tasman 20–40 million years ago.

Alan Cooper, an expert on ancient DNA at the University of Adelaide, led a team of experts there and at the South Australian Museum, who have managed to resolve the issue by sequencing DNA found in elephant bird bones. These were coincidentally found in the collections of Te Papa, The Museum of New Zealand, in Wellington (elephant bird bones are scattered across institutions worldwide, with the largest collection being in Oslo, Norway).

Once they had elephant bird DNA, the team could then use existing sequences from moa bones, as well as DNA from all the living species, to create the first complete genetic family tree for the group. Their results are published today in the journal Science, and the results have surprised everyone.

The small flightless tinamous of South America are close relative of NZ’s moas, while the diminutive kiwi is a close relative of Madagascar’s elephant birds, the largest members of the group. The relationships of the birds also suggest that flightlessness and giant size, developed independently many times in different lineages of these birds.

A 3m tall elephant bird (Aepyornis maximus) wanders through the spiny forest of ancient Madagascar (Illustrator: Brian Choo).

Flying birds survivors of a mass extinction

“There’s no way you can walk from Madagascar to New Zealand,” Alan told Australian Geographic. Even prior to 100 million years ago when the two were both part of the giant southern landmass of Gondwana, they were separated by Australia and Antarctica.

He argues that there is an inescapable conclusion.

“The evidence suggests flying ratite ancestors dispersed around the world right after the dinosaurs went extinct, before the mammals dramatically increased in size and became the dominant group… We think the ratites exploited that narrow window of opportunity to become large herbivores, but once mammals also got large, about 50 million years ago, no other bird could try that idea again unless they were on a mammal free island – like the Dodo.”

The researchers think they have an explanation for why the kiwi remained small, while its relatives grew to such huge sizes, too. By the time the kiwi ancestor arrived in NZ, the moa was already there filling a role as the large terrestrial herbivore; to carve out a niche for itself, the kiwi remained small, also becoming nocturnal and insectivorous.

“It’s great to finally set the record straight, as New Zealanders were shocked and dismayed to find that the national bird appeared to be an Australian immigrant,” Alan told reporters. “I can only apologise it has taken so long!”

John Pickrell is the author of Flying Dinosaurs: How fearsome reptiles became birds, available June 2014. Follow him on Twitter @john_pickrell. Additional reporting by Natsumi Penberthy.