On 11 May, 35 years ago, Tim Macartney-Snape stepped onto the summit of Mt Everest for the second time, in doing so, becoming the first person to have climbed the peak from sea level. He had walked from the Bay of Bengal across the dusty, populous plains of India, swam the mighty life-giving Ganges and trekked through the foothills of Nepal to the base of the planet’s highest mountain.

Speaking to camera on the summit, he said:

“All the way from the sea… and I’ve finally made it. We’ve all come from the sea…as a species we’ve reached a kind of peak, it’s time to climb the mountains of our minds, surely by understanding ourselves better we can end the suffering we impose on each other and this beautiful planet.”

Mountains loom large in Tim’s life, not just as a physical manifestation in the form of the many ranges he’s spent his life trekking, skiing or climbing, but as inspiration, solace and a metaphor for the human condition, what Tim sees as the conflict between our primal instincts and our rational intellect.

A lifelong love of heights

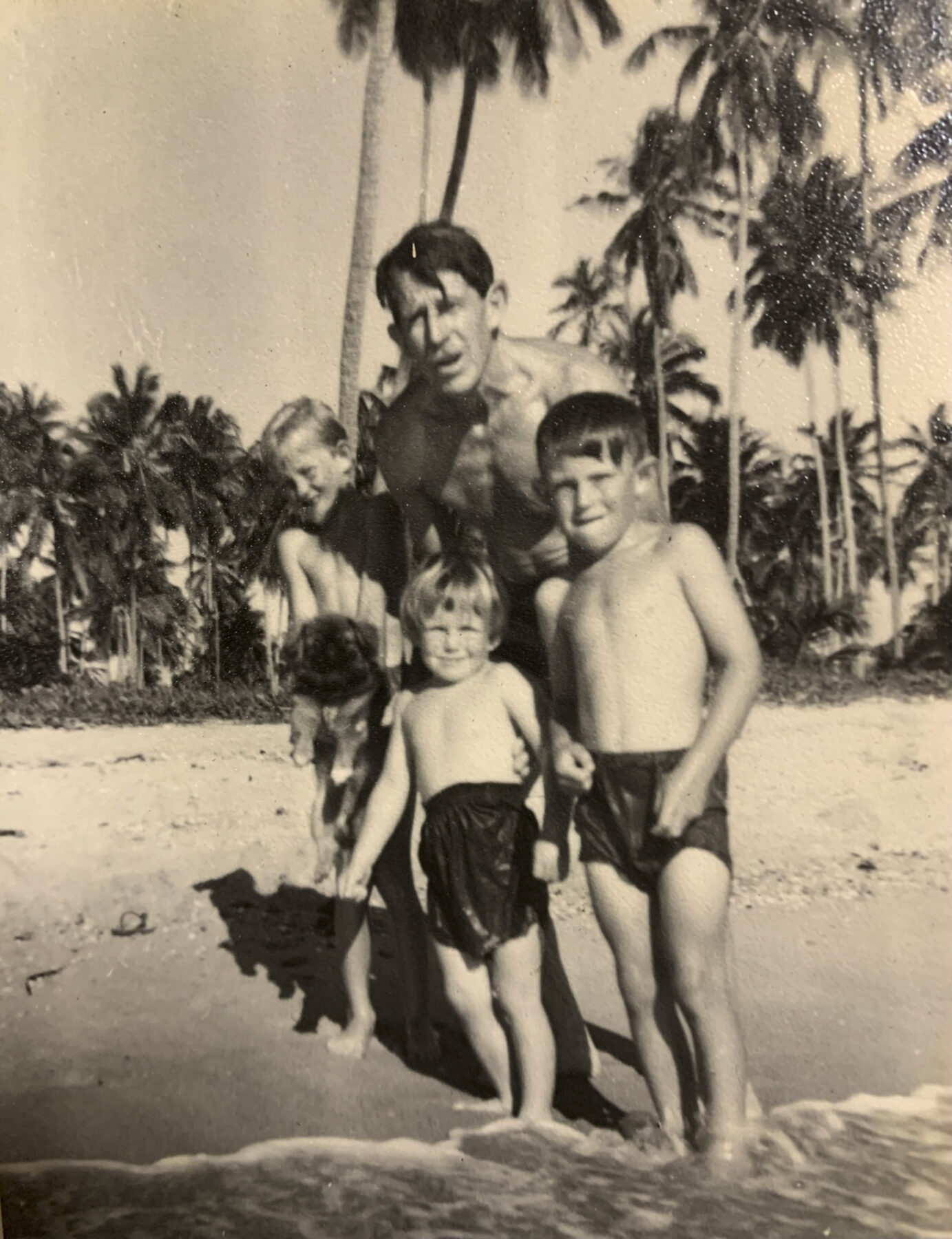

Where did this obsession with mountains originate? Maybe it’s from where he was born, in the Southern Highlands of Tanganyika Territory (now Tanzania), where his parents, Jack and Bobbie, ran a successful farm at altitude. Or maybe it’s from his time as a boarder at school in the north of the country where Mt Meru and Kilimanjaro dominated the landscape. But it could just be simple genetics, the product of inheriting a good set of lungs and a lust for adventure.

Jack, who was born in 1896 (Tim was born in 1956, when his dad was 60), served in WWI, where he was awarded a Military Cross and bar before nearly dying after being hit in the chest by shrapnel near the Somme. After the war, in search of adventure, he and a mate left Australia to go to Africa to prospect for gold, which Jack soon gave up for the more pragmatic option of farming. Then when Jack was in his mid-50s, due to relationship difficulties, his first wife convinced him to sell their Tanganyikan farm and retire to England. But Jack clearly still had itchy feet.

According to Tim’s youngest sister, Pip, one day Jack read about a new technique used in Ireland to better preserve the nutrition in hay, “He said I’m going to go out there and have a look – and there was mum and that was it.” Bobbie, who was staying with her grandmother in Ireland, was also interested in farming and involved in this new hay-making technique. She was also equally adventurous. So they returned to Africa, to farming, and had four children (he’d had one son, Ewan, with his first wife).

Tim was born on the farm in Tanganyika in 1956, where life sounded rather idyllic, producing a range of foodstuffs for the capital. Pip says that as a child Tim always loved practical jokes. “One time though, it really backfired. He knew our elder sister hated snakes, but he found a dead snake, took it home and curled it up on the step of her bedroom. She nearly had a heart attack.”

Their parents were, according to Pip, “deeply Victorian in their values”, and Tim and his older sister were sent to boarding school two days’ drive away at an early age, returning to the farm during holidays.

In 1961, Tanganyika gained independence from Britain, then in 1964 it merged with Zanzibar to become Tanzania. More change arrived in 1967, when the government embraced socialism, which included the collectivisation of farms. The farm, which Jack and Bobby had built into a very profitable business, was sold to the government. However, they were unable to pull the money out of Tanzania and, at the end of 1967, Jack returned to Australia essentially broke. Fortunately, he had a large extended family and they were able to help the family purchase a small farm near Benalla.

Because Tim’s father had gone to the prestigious Geelong Grammar, Tim was fortunate enough to get a scholarship, so it was back to boarding school, where he was badly bullied for his slightly foreign accent. In Year Ten, students decamped for the year to the school’s Timbertop campus, near Mt Buller in the Victorian Alps. “Timbertop was my lifesaver. It was fantastic because we’d submit a hiking plan and then we were allowed to head off on Friday afternoon to return Sunday evening. It was an amazing thing to be able to do as a 15-year-old. We got up to all sorts of adventures, some of which definitely would not have been condoned by the school,” he says.

The beginning of great things

After finishing school, Tim went to ANU to study science, which he chose because Canberra was small and close to the mountains. In his first week there, he met Lincoln Hall, when he signed up to the ANU Mountaineering Club and, though they didn’t know it at the time, they were to become long-time climbing partners.

Tim was soon climbing on the crags around Canberra and learning his mountain craft in New Zealand’s Southern Alps, the traditional first stopping place for Australian mountaineers. Then in 1978, Tim and Lincoln took part in the club’s expedition to Dunagiri (7066m) in the Garhwal Himalaya in India. Towards the end of the expedition, when everyone was ready to give up, the youthful pair of Tim and Lincoln made one final attempt on the mountain.

In his book, Himalayan Dreaming, Will Steffen wrote of their summit attempt, “They had brought with them sleeping pads, down jackets and bivvy bags, but no tent, stove or sleeping-bags.” After a night out in the open, the pair made their summit attempt despite a lack of water and Lincoln’s frostbitten toes, with Tim alone reaching the top. They returned to camp after 49 hours out in the open, including 36 hours without water. Lincoln subsequently lost parts of two toes, but they proved to themselves that they had what it took to push it to the extremes.

What followed were years dedicated to climbing some of the world’s highest peaks. In 1981, Tim climbed the aesthetic Ama Dablam (6812m) as part of a small lightweight team. He summited the notoriously difficult and dangerous Annapurna II (7937m) in 1983. The summit was five vertical kilometres above Advance Base Camp, and they had to spend five days storm-bound in a snow cave at 7100m (with only Simone de Beauvoire’s Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter to read between them), followed by two more nights on ledges carved out of the snow. The descent was so epic they were days late and back in Australia it was reported that they had gone missing.

In 1984, Tim and Greg Mortimer became the first Australians to summit Mt Everest as part of a small Australian expedition that also included Lincoln, Geoff Bartram and Andi Henderson. British climber and writer, Walt Unsworth, wrote that “the Everest Expedition of 1984 was a model of what an expedition should be. Not only that, but their actual achievement was also astonishing; one of the greatest climbs ever done on the mountain.” Andrew Lock, the first Australian to climb all 14 8000m peaks, says of their ascent: “I think it pushed the boundaries of what even veteran Himalayan ascensionists had thought reasonable. Being a [bottled] oxygenless ascent of a new route on a massive, extremely threatening face on the highest peak in the world, completed in spite of the loss of key equipment, was truly extraordinary.”

Tim and Greg reached the top of Everest as the sun was setting, and descending in the dark was touch and go, with Greg near catatonic with exhaustion. Andi had gotten stuck 50m below the summit because his hands had frozen into claws and he couldn’t change out of his sunglasses as it got dark (he would later lose the tops of nine fingers). At one point the three had to abseil over a cliff tethered only to aluminium pack stays that Tim buried in the snow and then drop off the end of the rope because it didn’t reach the bottom.

A new approach

It was a couple of months after this expedition that the seed of the sea to summit ascent of Mt Everest was planted with a deliberately cheeky challenge from Australian filmmaker, Michael Dillon. In Tim’s book about the expedition, Everest: From Sea to Summit, he quotes Mike: “No one, including you, Tim, has really climbed Everest properly.” Because, Mike explained, the mountain’s 8874-vertical-metres are measured from sea level, the mountain really should be climbed from there. The idea lodged in Tim’s brain, in part because Dick Smith said he would sponsor any such attempt through his magazine, Australian Geographic.

But it would have to wait. In 1986, Tim did the second ascent of Gasherbrum IV (7980m) with fellow Australian, Greg Child, and American, Tom Hargis. The three survived a night out without sleeping bags or stove just below 8000m, while the descent was fraught. At one point, Tim slipped while trying to salvage a precious piton for use further down. “I must have gone about 20m, pendulumed and bounced off the rock once, ripped my down suit open and probably cracked a rib.” Fortunately, Greg managed to save him with a boot-axe belay (just the rope wrapped around the head of an ice axe pushed into compressed snow and buttressed by a boot on the downhill side).

The Sea to Summit expedition was planned for 1990. The year before, Tim had married Ann Ward, a doctor he’d met while running a trekking expedition in the Himalaya. Ann had subsequently gotten a job working for the Royal Flying Doctor Service and so Tim ended up training for the world’s highest peak in one of the world’s flattest places, Meekatharra in Western Australia.

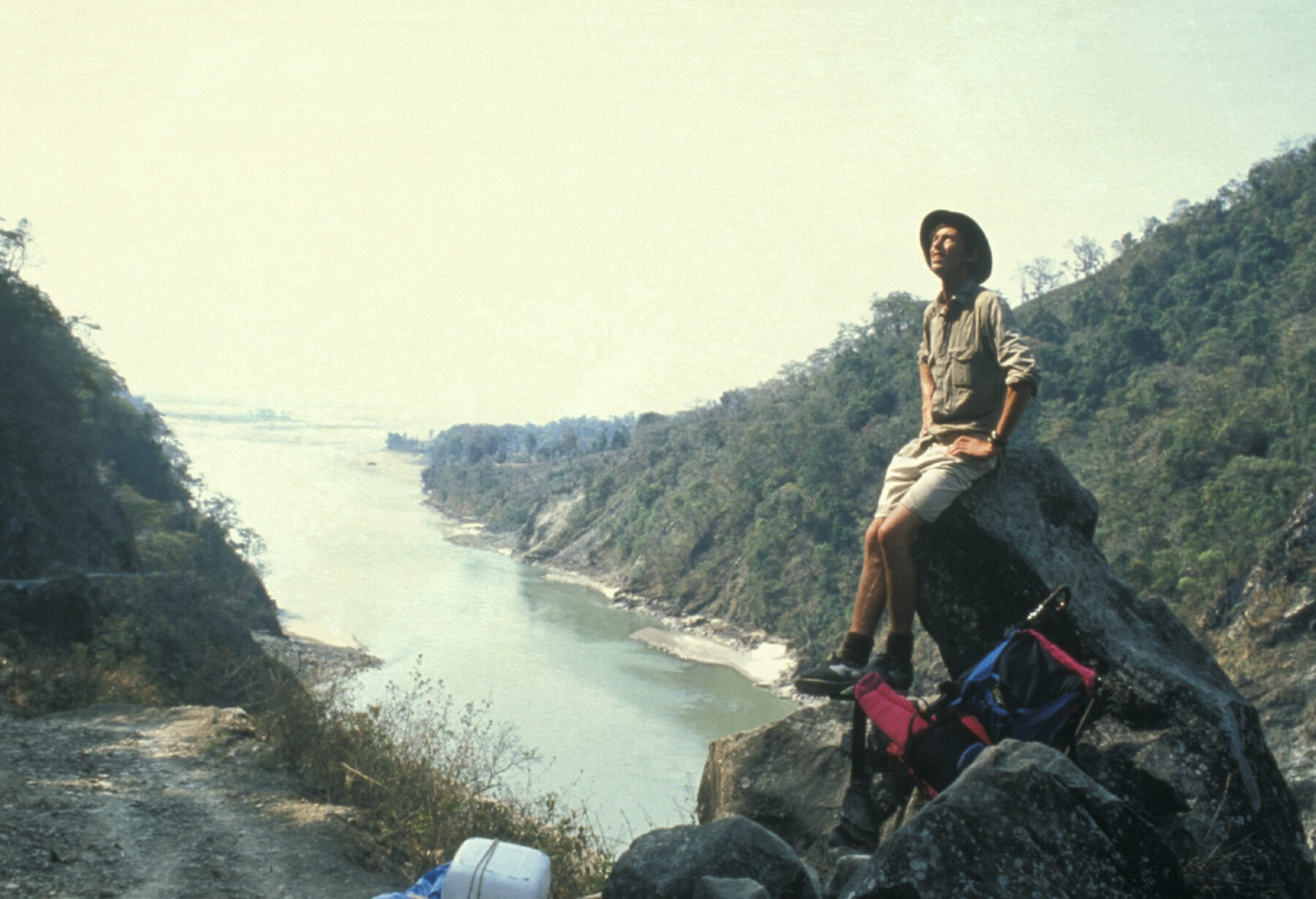

Tim and Ann flew out of Australia for India on Australia Day in 1990. Officially beginning the expedition with a swim where the Hooghly River meets the Bay of Bengal. From there, Tim headed north on foot with his support crew, including, among others, Ann, Michael Dillon and Pip.

The walk would take Tim more than 1000km across India, over the border into Nepal and through the foothills of the Himalaya to Everest, which he planned to climb solo without bottled oxygen via an ambitious traverse, ascending the West Ridge and then descending the standard South Col route.

A journey through a wild world

In his book, Tim evocatively describes his trip across India, the chaos and pollution of India, the constant unembarrassed curiosity of onlookers, the environmental degradation, and the almost overwhelming poverty. Reflecting on what he saw, he wrote, “My desire to seek out the most unspoilt piece of country is born not of a wish to turn the clock back but of a hope that one day the dual facets of human nature, which have made us the most destructive force ever to walk the Earth yet at the same time the most loving and sensitive, will be reconciled and mankind can look forward to a saner future…”

Pip remembers a few things about the trip through India vividly. The blisters, because it was so flat. “Every step was the same, and we got blisters on blisters on blisters.” There were also the onlookers. “We’d sit down in a teashop and by the time we finished every single crack and hole, and window would be filled with heads because the word had got out that we were in this teashop and literally everyone would be trying to get a glimpse of us,” says Pip. “If you went to go to the loo, you’d be followed by this train of children.”

Tim survived a swim across the holy Ganges, which is notorious for all the human and animal effluent that runs into it. Due to some issues at the border with Nepal, he had to make a 300km detour from the intended route, ending up running it over five days to save time. It took two months to arrive at Everest Base Camp on foot.

Tim’s planned route up the West Ridge of Everest climbs steep cliffs above Base Camp to the saddle of Lho La. Tim teamed up with some Swiss climbers, helping them fix ropes to Lho La, from where he had to climb exhausting, avalanche-prone snow and ice slopes to the West Shoulder. Above the West Shoulder there were still kilometres of complex snow and rock climbing to the summit of Everest.

Tim spent a difficult night acclimatising on the shoulder before descending. Soon after, there was heavy snowfall, which was alarming as Tim knew the West Ridge was very avalanche prone. What followed was a period of indecision, Tim’s desire to climb the more challenging West Ridge competing with knowledge that it would be extremely risky, particularly climbing alone.

A decision borne of experience

Finally, Tim decided to abandon the West Ridge. In his book, he wrote about the decision: “Indecision is wearisome in the extreme, and I felt that a great burden had been lifted from my shoulders. I was no longer going to do the ultimate climb I had been dreaming of, but I would devote everything I had in me to what I had decided to do. Even the normal route [South Col route] was going to be difficult and might even turn me back.”

Though the burden of indecision had been taken from him, so too had the thirst that comes from something new and daring. “I’d written the normal route off so much that when I actually came to do it, I lacked the kind of mental momentum you need. I was unable to transfer the ambition from the West Ridge to the normal route, and I found it incredibly hard going,” Tim says.

Tim loves problem solving and the normal route also lacked the technical challenges that he finds so engrossing, which probably turned it into more of a grind. Normally so strong in the mountains, Tim in his book writes about one morning heading towards the summit with rare vulnerability:

Nothing has ever seemed as lonely and desolate as leaving that wreck of a camp at 3.30 in the morning to head up an icy slope that seemed never to end. Until the feeble exercise I was performing warmed me a little, I was racked by shivering. I felt utterly miserable and wondered what on Earth I was doing in such a desolate place.

But Tim has developed immense depths of resilience, which perhaps is the very essence of why he’s a twice honoured Order of Australia recipient. His long-time climbing partner, Lincoln said of him: “People are amazed when they meet him for the first time – with his Prince Charles ears and Twiggy legs – but what a lot of people don’t see because it’s not on display is his extraordinary drive.”

When I asked Pip what she thinks drives Tim, she mentions several things. First, he discovered something that he was incredibly good at – testing has proved he has big lungs –and he’s driven and competitive. Tim also takes joy in pushing his limits, writing in his book: “The thrill lay not only in the spectacular scenery and the adventure of solving the problems of an ascent, but also in taxing the mind and body beyond all imaginable barriers of hardship. Nothing else in life made living so keen, urgent and wonderful and everything I normally took for granted so important, indeed so beautiful.”

On the morning of 11 May, Tim stepped onto the summit of Everest for the second time. “So there it was before my eyes again, but this time more real, not just because others were there, but because I was arriving in the full light of a perfect day,” he wrote in Everest: From Sea to Summit.

Looking back on the ascent now, Tim says, “I think I’ll always regret that I wasn’t able to do a traverse.” At the same time, he’s pragmatic enough to know that he may never have made the top via the West Ridge or gotten back down.

A new appreciation

There is a sense in his book that Tim was ready to do other things than climb big mountains, and 1991 brought two big life changes. Tim and Ann divorced, and he started up an outdoor equipment brand called Sea to Summit with gear designer, Roland Tyson. The company initially started with cleverly packaged outdoor accessories and slowly built its expertise with materials to become what is now a global brand.

Tim sold out of the company in 2017 and, these days, at the age of 69, seems to live a rather idyllic life, spending the time he’s not travelling on 40 acres of bush in NSW’s Southern Highlands with his partner of 32 years, Stacy (Pip lives just a couple of hundred metres away with her family). His spare time is spent climbing and skiing and he does occasional work giving inspirational talks and guiding for World Expeditions.

As a founding director and patron of the World Transformation Movement (WTM) – which is based on the ideas of Australian biologist, Jeremy Griffith, much of Tim’s time is spent narrating podcasts communicating the ideas. The crux of which is a biological explanation for the human condition: that humans are psychologically burdened by a conflict that arose when our fully conscious, thinking mind developed and began to wrest control over our original, cooperatively-oriented instinctive brain. This internal clash inevitably caused us to become angry, egocentric and alienated, leaving us immensely insecure. The frustration of which saw the breakout of war and destruction, the excesses of which our species has through the ages tried to quell with civility and religious restraint. By understanding this clash, Tim believes we can climb the ‘mountains of our mind’ healing ourselves through a compassionate understanding of why we became so psychotic.

Reflecting on the expedition now, Tim says climbing Everest from Sea to Summit didn’t really make it harder, what it did give him was a better understanding of how many of the world’s people live, “For most of them, life posed enough of a challenge without having to think about mountains.” Perhaps for Tim, the lasting gift of walking from the sea was a deeper understanding of the privilege of being a climber, and a profound appreciation of people’s humanity in the face of so much suffering.