The twists and turns in snake evolution

THE FIRST SNAKES were likely both eel-like swimmers and worm-like burrowers, a new study suggests, contraditing previous research that suggested the first snakes were burrowers.

The new study used CT scans to create three-dimensional structures of the inner ear bones of 80 snake and lizard species, including living semi-fossorial and semi-aquatic snakes as well as a primitive fossil snake of the genus Dinilysia.

Analyses of these 3D structures helped tackle an ongoing controversy. “There is controversy over which environment drove the origin of snakes: the earliest snakes may have been eel-like swimmers or worm-like burrowers,” says Alessandro Palci, from Flinders University, who led the new study.

A correlation exists between an animal’s environment and the shape of its inner ear, Palci explains, which helps researches infer the habits of a species from the inner ear bone structure. “We found that the inner ear of Dinilysia resembles snakes that both burrow and swim. Thus, the earliest snakes might have frequented both environments,” Palci adds.

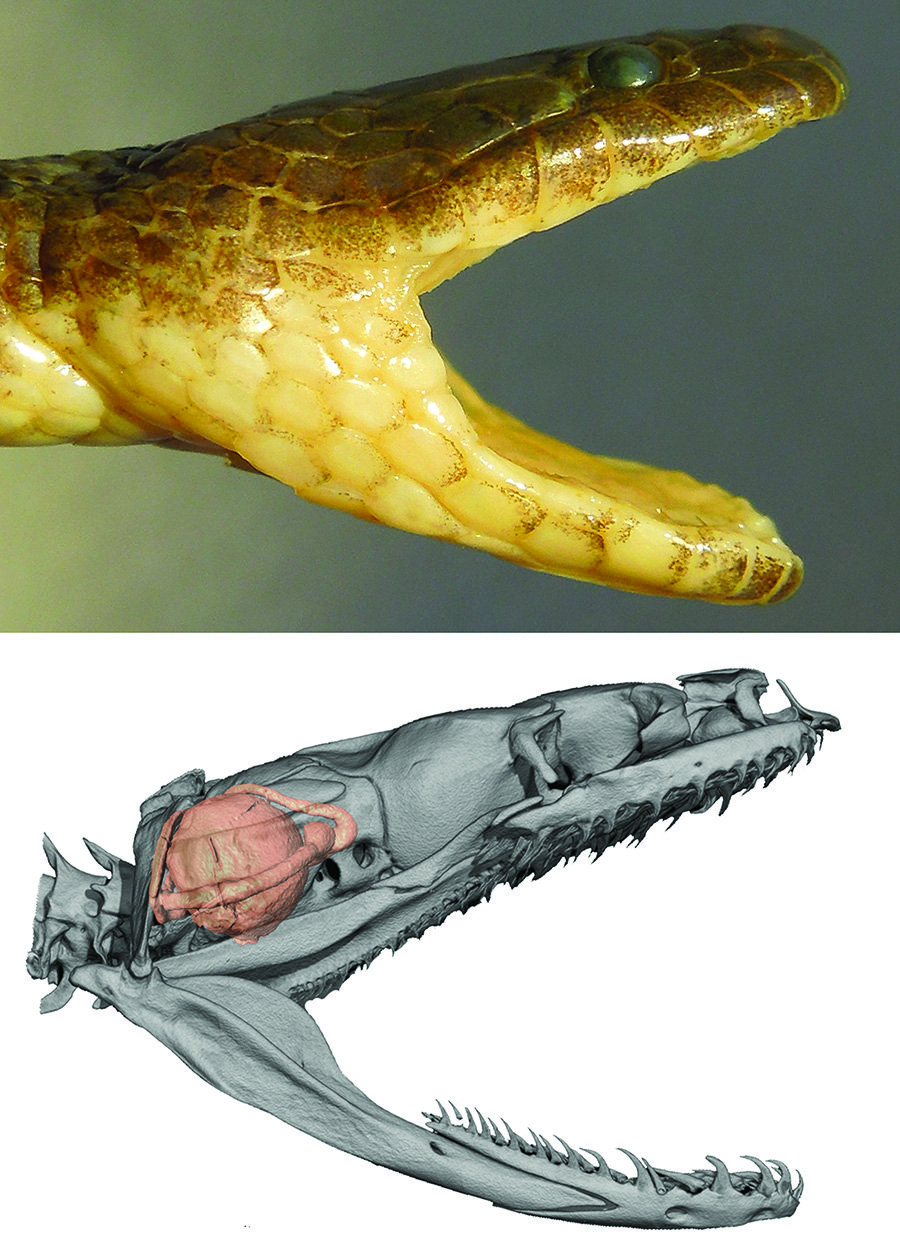

Head (top) and skull (bottom) of the semiaquatic snake Myron richardsonii. The morphology of the inner ear of this snake(highlighted in pink) is very similar to that of the early fossil snake Dinilysia patagonica, and suggests similar ecological habits. (Image credit: Alessandro Palci)

An ongoing debate

The question of whether modern snakes evolved from swimming or burrowing ancestors has been dangling in the mind of researchers for more than a hundred years.

“Their very flexible skulls and extremely elongated bodies are strikingly different from their closest relatives, lizards. For well over a century, researchers on snake evolution have being arguing on whether snakes evolved their elongate body to be better at burrowing (like worms) or be better at swimming (like eels). The debate is still ongoing, and any new evidence added to the pile can help us find the answer,” Palci says.

Partial skull of the fossil snake Dinilysia patagonica at the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia.” The snout pointing to the right. (Image credit: Alessandro Palci)

The findings of the study suggest that both ideas might be partly right. “There are striking resemblances between the inner ear region of the primitive snake Dinilysia and some semi-aquatic snakes, as well as certain burrowing forms,” Palci adds.

The findings make sense, according to co-author Michael Lee, from Flinders University and the South Australian Museum, as it would explain why so many ancient snakes are aquatic, fossorial, or both. “And living snakes continue to excel in those habitats: modern sea snakes are the most rapidly speciating group of reptiles, while the worm-like blind snakes are found in every continent,” he adds.

These results show that the evolutionary path followed by snakes is more complicated than previously thought. It is not just a question of whether they were swimmers or burrowers, says co-author Michael W. Caldwell, from the University of Alberta in Canada. “We go to great lengths to point out that modern and ancient snake ecologies are far more complex than such simple dichotomies would suggest,” he adds.

But further research is still needed, explained Hongyu Yi, from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, at the Chinese Academy of Science, who led a previous study suggesting the first snakes had burrowing habits.

“The new study provides very important samples of these semi-aquatic forms, confirming that these snakes have relatively larger saccule than pelagic marine snakes,” Yi says. The saccule, one of the inner ear structures, is enlarged in fossorial snakes and this new study shows that semi-aquatic snakes also have this enlarged structure.

“But how large is large? Can we distinguish these semi-aquatic forms from fossorial forms? More studies are needed to answer these new and interesting questions,” Yi adds.

New research headed to Australia

Now Palci plans to continue his research focusing on two ancient Australian snakes, which may hold clues to the evolution of this group.

“These snakes are Wonambi, a snake that went extinct about 50 thousand years ago, and the much older Yurlunggur, which lived sometime around 20 million years ago. These snakes are important because they are part of a very ancient lineage that, similar to other animals like the platypus and the echidna, survived in Australia much longer than anywhere else likely due to the isolation of this continent,” Palci says.

The findings were published in the Royal Society.

Partial skull of the fossil snake Dinilysia patagonica (type specimen) at the Museo de La Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina. the snout pointing to the right. (Image Credit: Alessandro Palci)

READ MORE: