Hidden housemates: the termites that eat our homes

MOST OF OUR hidden housemates are harmless. But when it comes to termites, some can literally eat us out of house and home.

While termites’ ability to damage our homes by eating wooden foundations is legendary, most species do not cause problems. Usually they are rarely seen, hidden away inside wood, underground or in their nests.

The importance of termites

Termites eat cellulose – the complex sugars that plants use to build leaves, stems and trunks. Cellulose is the most abundant organic compound on earth. To find wood and other cellulose sources, termites often construct miniature, private highways under the soil that can radiate more than 50 m from their nests.

Perhaps the most famous termite nests are those made by the magnetic termite, Amitermes meridionalis, in northern Australia. These nests are oriented in a north-south direction. Many other species build mounds of different shapes and sizes, while others nest in wood, underground in the soil, or in trees.

The distinctive nests of magnetic termites in northern Australia. (Photo credit: Author provided)

The combined mass of termites on earth is estimated at 445 million tonnes, putting them in the top ten alongside cattle, krill, ants and humans.

Outside our homes, termites play a critical role as carbon recyclers and are considered keystone species in many tropical ecosystems, such as savannah habitats like those of northern Australia, Africa and South America. They use nutrient-rich saliva and gut excretions to build tunnels, which improves the quality of the soil. Alongside ants, there is evidence that termites increase crop yields.

When winged adult termites emerge from the nest they become a feast for many animals across the tropics.

Cockroach relatives

Termites evolved more than 140 million years ago from social cockroaches that burrowed deep into rotting wood. The closest living relatives of termites are cockroaches from the genus Cryptocercus, found only in isolated mountainous areas of China, Korea and North America.

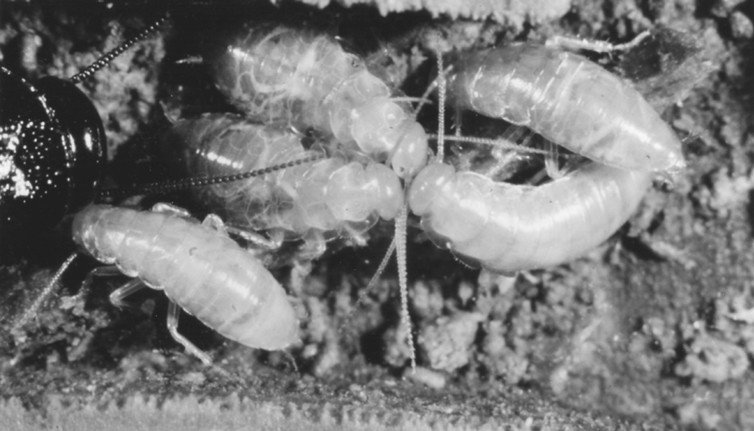

Mum and dad Cryptocercus pair up and burrow into a large log that will be their home (and source of food) for life. Soon after meeting, the female lays a single clutch of 10 or so offspring, which they both feed and look after for around three years – about half the life of a typical Cryptocercus.

The social cockroach Crypotcercus with its pale young. (Photo credit: Dr Christine Nalepa)

As termites evolved, their firstborn offspring began to look after the next clutch of siblings, freeing mum and dad to produce more sons and daughters. The older siblings stayed to build and defend the colony, and feed and look after the young.

The population of a termite colony these days can number in the millions. All the offspring derive from of a single reproductive pair (the queen and king).

Some species have evolved alternative systems. Colonies of the Australian termite Nasutitermes exitiosus often contain up to four unrelated pairs living together with their countless offspring in apparent harmony – a bit like a 1960s hippie commune.

In the Japanese termite Reticulitermes speratus, the king tends to outlive the queen. But the queen produces many half-clones of herself without any genetic input from the king (a form of virgin birth). These clones replace their dead mother, and all mate with the remaining king. In one colony, over 600 of these queen-clones have been found, making it the largest harem known in the animal kingdom.

A termite queen (centre) surrounded by workers. (Photo credit: eyeweed/Flikr, CC BY-NC-ND)

One giant organism

The vast majority of termite offspring within a colony will never reproduce. Instead, these worker and soldier termites remain in a state of suspended development, never becoming adults. Soldier termites attack predators to ensure the survival of the colony and have evolved impressive jaws or snouts that spray toxic chemicals.

In some species like Neocapritermes taracua from South America, workers sacrifice themselves through the use of an “explosive backpack”. They do this by rupturing their skin, which allows normally harmless chemicals to mix and produced modified chemicals that are dangerous to any nearby predators.

All the efforts of the workers and soldiers go towards raising a small proportion of their brothers and sisters to adulthood, usually once a year. This select few will grow wings (all four of which are almost identical, hence the scientific name Isoptera meaning “equal wings”), pair up and promulgate the genes they share with their siblings back home.

Living with us

The dark, humid areas under the floor of many Australian houses provide the ideal environment for termites to emerge from the soil and create their covered highways up foundations to a mother-lode of wooden frames.

In Australia, about a billion dollars is spent each year on termite control. House-eating termites are most common in the tropical north, although they are found throughout the continent. While there are more than 300 species of termite, only a handful are considered pests.

Most termites are deterred with chemicals and by replacing damaged wood with treated timber.

Their sophisticated social system is also their Achilles heel. Termite baits contain slow-acting chemicals that prevent termites from moulting or disrupt their nervous systems. Workers voraciously feed on the bait and take it back to the colony, where the poison is spread to the queen, king and their new offspring.

But as one colony is killed, another is often ready to take over. Termites have been around a long time and they are not likely to go away any time soon.

![]()

Nathan Lo is Associate Professor at the School of Biological Sciences, University of Sydney.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

READ MORE:

- Hidden housemates: Australia’s huge and hairy huntsman spiders

- Land of white cockaroaches

- Hidden housemates: The redback spider

- Scientists use termites to find gold