Honeysuckle Creek: the little-known heroes of the Moon walk broadcast

The Dish portrays Australia’s role in relaying live television footage of the first man on the Moon during the 1969 Apollo 11 mission. But it omits the pivotal role of NASA’s Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station, about 300km south of the Parkes Observatory, near Canberra.

Honeysuckle provided the historic live footage of Neil Armstrong steppi ng onto the Moon that was seen by more than 600 million people worldwide at 12.56pm (AEST) on Monday 21 July 1969.

Andrew has made it his mission to right the record and recognise the crucial role of the Honeysuckle team, particularly station director at the time Tom Reid, in bringing those images – some of the most watched footage in human history – to the world.

This story was originally published in Issue 151 of Australian Geographic. Purchase your copy here.

The little-known heroes of the Moon walk broadcast

AFTER 19 YEARS as a member of the NSW Legislative Assembly, I stepped down in 2007 and took up writing, mostly biographies.

I knew Tom Reid, who’d been the station director of NASA’s Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station during the Apollo 11 mission, through his daughter Marg – we’d dated during the early 1970s.

Although I didn’t understand exactly what role Tom and his team at Honeysuckle had played in televising the live broadcast of Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon, I knew it had been important and I wanted to tell Tom’s story.

I knew him well enough to understand that he would never have agreed to me writing about his NASA career. Not one to blow his own trumpet, Tom would have done his best to dissuade me.

It wasn’t until after Tom Reid’s death in 2010 that I began to scope out the possibility of a book about Honeysuckle Creek.

A number of Tom’s former colleagues, among them his deputy at the time, Mike Dinn, were still in a position to talk to me.

And Dinn got straight to the point: “The Dish implies that Parkes was the communication facility in Australia for Apollo 11. The truth is that Honeysuckle Creek was.

Parkes was and is a radio telescope – not a tracking station. Parkes had no transmitter and so could not send commands or voice to the spacecraft.

So ‘Parkes go for command’ as used in the movie is completely wrong and misleading. And the movie studiously avoids stating that the first TV transmission to Australia and the world came from Honeysuckle Creek.”

Hooked by the realisation that it was a little dish outside Canberra that had brought the live television of Neil Armstrong’s first step on the Moon to a then-record worldwide audience of 600 million viewers, I decided to write Honeysuckle Creek: The Story of Tom Reid, a Little Dish and Neil Armstrong’s First Step, a book about Honeysuckle intertwined with the story of Tom Reid.

Read more: How to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing

The pivotal role of Tom Reid

TOM, A GLASGOW-BORN ELECTRICAL engineer with a naval background, began his career with NASA in the late 1950s in the remote outback town of Woomera, in South Australia.

His first job at Woomera was to track British medium-range ballistic missiles for the Weapons Research Establishment. But following the orbital flight of Sputnik I – the world’s first artificial satellite – in 1957, NASA came calling and Tom began tracking satellites for the Americans.

An orbiting satellite could only be tracked from any single point on Earth for about seven minutes and so NASA built some 18 tracking stations around the globe, including one at Woomera.

For voyages to and from the Moon, however, a network of more sophisticated tracking stations was required.

Three were built: one at Goldstone in California; one near Madrid, in Spain; and one at Honeysuckle Creek, outside Canberra.

Placed roughly equidistantly around the globe, each had a view period of about eight hours. So, as the Earth spun on its axis once every 24 hours, these stations were collectively able to continuously communicate with astronauts on or near the Moon.

Without these three stations, Mission Control in Houston, in the USA, would have been deaf, dumb and blind to Apollo astronauts.

The Apollo tracking stations had transmitters powerful enough to send ultra-high-frequency radio signals at a speed of about 299,338km/s.

These signals carried a voice link and remote commands to the spacecraft, as well as a ranging code to determine exactly where the astronauts were.

The stations also had sensitive receivers to pick up the astronauts’ voices, the returning ranging codes and, most importantly, telemetry (or data) relating to such things as the astronauts’ heartbeats and their spacecraft’s fuel levels.

Travelling at the speed of light, these radio signals took just a second or so to cover the 804,672km round trip, from Mission Control in Texas to the astronauts on the Moon and back, so they could converse in almost real time.

Opened in early 1967, Honeysuckle at first had no Apollo spacecraft to track. Instead, NASA conducted gruelling simulations. These soon revealed Honeysuckle’s woeful performance compared with the other stations.

Although Honeysuckle’s first director, Bryan Lowe, was highly intelligent and personable, he struggled with detail and was unable to meld his tracking team into a smoothly functioning unit.

Unlike Goldstone and Madrid that had Americans in all key positions, there was not an American accent to be heard at Honeysuckle. It was government policy that the director had to be a citizen or permanent resident of Australia.

As the government searched for a new director, Tom’s name stood out.

With almost a decade of space tracking experience, his hard-driving, no-nonsense style and ability to lead a diverse team of engineers and technicians made him the natural choice.

Within months of his appointment, Honeysuckle had been transformed from the worst performing Apollo tracking station into the best.

Under Tom’s leadership from August 1967, Honeysuckle tracked successive Apollo missions 7, 8, 9 and 10, each with great success.

To broadcast or not to broadcast?

BY MID-1969, NASA WAS ready to launch Apollo 11, the mission earmarked to fulfil President Kennedy’s promise, made in 1961, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth before 1970.

Just a few weeks before the launch, NASA resolved an internal debate that had been raging since 1961: was it necessary or desirable to attempt live TV coverage of the moment the first person stepped onto the Moon?

Those against broadcasting the event were concerned about the heaviness of a camera. Weight on the Apollo Lunar Module was so critical that the astronauts’ seating had to be discarded, requiring them to stand while flying.

Those in favour of the broadcast argued that American taxpayers, who had stumped up billions of dollars for the Apollo program, had a right to see live in their lounge rooms the moment an astronaut first stepped onto the Moon.

The development of super lightweight cameras sways decision

Following the development of a super lightweight camera, advocates for televising the event won the day. But with space aboard the Lunar Module at a premium, this equipment was mounted in a way that it began filming from an upside-down position.

Because of this, a special reversing switch was fitted on each of the Apollo tracking stations’ TV scan converters, to allow a technician to flip the upside-down TV image the right way up.

In the weeks leading up to the launch of Apollo 11, the radio telescope at Parkes, located in central NSW about 300km north of Honeysuckle, was added to NASA’s array of Australian dishes for extra backup.

Although it couldn’t transmit anything, Parkes’s 64m-diameter dish made it an excellent receiver compared with Honeysuckle and its 26m-diameter dish.

At that size, however, the Parkes dish could only be angled down to 30 degrees above the horizon. But the Honeysuckle equipment, being a special Apollo dish, could be angled down to zero degrees to the horizon.

Although Canberra and Parkes were on roughly the same longitude and the Moon rose over them at about the same time, this difference in the minimum angulation of the dishes meant the Moon rose over the Honeysuckle dish two hours before it rose over the Parkes dish.

Lift off

On 16 July 1969, the day Apollo 11 blasted off from Cape Canaveral in Florida, USA, NASA’s Australian dishes included: Carnarvon, in Western Australia, which was used to track the first and last hours of the mission; Honeysuckle Creek, which tracked the Command Module when it was in separate flight; a deep space tracking station at Tidbinbilla, just north of Honeysuckle, which was used to track the Lunar Module; and Parkes, which provided a downlink backup.

All but Carnarvon were rigged up to receive the Lunar Module’s downlink TV signal.

Two days after the Apollo 11 launch, however, a fire at Tidbinbilla resulted in a switch of duty.

Honeysuckle would track the Lunar Module and, when the two vehicles were operating separately, Tidbinbilla would be responsible for the Command Module.

The Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station complex was located in the ACT’s geographic centre, on and immediately below a ridge that sat saddle-like between two granite peaks.

It had been built on a series of terraces bulldozed out of the mountainside to create a 5.7ha clearing among the eucalypts.

Secured to the top of the ridge was the station’s most prominent feature – its 26m dish – the apex of which was almost 1200m above sea level.

The station’s operations building and power generators were on the terraces below. Snow often fell at the site during the winter months, especially in July.

With the Moon landing scheduled for just after 6am on Monday 21 July (AEST), Tom Reid had stayed over at the tracking station the previous night and was up early to listen in to Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin as they flew their Lunar Module towards the Moon’s surface.

Although the Moon would not rise over Honeysuckle until just after 11am, Reid could hear the astronauts talking to Mission Control through NASA’s communication net. And just after 6.15am, he heard Armstrong say: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

According to the Apollo 11 flight plan, Armstrong and Aldrin were not due to take their Moon walk until about 4pm.

At that time their connection to Mission Control would be via the dishes at Honeysuckle and Parkes, with the much bigger Parkes dish earmarked as the prime receiver of lunar TV footage.

Armstrong and Aldrin, however, didn’t want to wait that long.

Buzz Aldrin (left, at left) and Neil Armstrong, at Manned Spaceflight Centre, Houston, take a break from training for the Apollo 11 lunar landing mission. Buzz holds tools designed for picking up rocks from the Moon’s surface., guided under the distant eye of Mission Control. (Image credit: NASA)

The moon walk

Just after 8am, they convinced Mission Control to let them conduct an early Moon walk, to commence as soon as they had completed their post-landing checks, eaten something, and suited up. NASA’s new best estimate was that Armstrong would take his first step at about 11am.

At that time Goldstone would still be receiving a good signal, while the Lunar Module would just be coming into view of Honeysuckle. The moonrise over the Parkes dish, however, would still be more than two hours away.

Just before 9am, as the Honeysuckle team scrambled to adjust to this demanding new timetable, prime minister John Gorton turned up for a station tour.

Believing he had little choice in the matter, Tom had reluctantly agreed to this VIP visit the previous evening. But knowing that his team would be less than impressed by the prospect of such an interruption, he hadn’t forewarned them.

As the prime minister toured the operations building for almost an hour, some of the trackers cursed under their breath as they suddenly became aware of Gorton and his entourage hovering behind them.

After Honeysuckle’s dish had been moved out of its tracking alignment for a prime ministerial photo opportunity, Gorton departed at about 10am and Tom and his team were able to refocus on final checks with Mission Control.

At 11.15am the Moon rose over the gum-tree covered horizon beside Dead Mans Hill, upon which the receivers on Honeysuckle’s dish locked on to the Lunar Module’s signals, which were being generated by its tiny 66cm antenna.

The astronauts’ voices and telemetry now streamed into Honeysuckle’s operations control room.

After being processed by the station’s computers, these signals were forwarded to Houston, all at a speed that made it possible for Mission Control to have a conversation, in almost real time, with Armstrong and Aldrin.

Televising the moonwalk

Inside the Honeysuckle Creek facility during the Apollo launch. (Video courtesy of the CSIRO)

ALL THE WHILE, THE astronauts were suiting up in the Lunar Module. To survive during their Moon walk, they had to turn themselves into what amounted to small self-contained spacecraft, capable of maintaining Earth-like conditions around their bodies and ongoing communications with Mission Control.

Specially cooled and ventilated, their space suits were bulky and cumbersome to put on, and this took much more time than expected. But the astronauts were in no hurry.

To make a mistake was to chance a horrible death by asphyxiation: their lungs would collapse as the air in their hearts bubbled and their blood vessels ruptured, all within a minute or so.

It wasn’t until sometime after 12.30pm that Neil Armstrong sounded like he was ready to emerge from the Lunar Module.

Back on Earth, a record live-television audience of 600 million people – then, almost a fifth of the world’s population – listened to various commentators doing their best to fill in time as they waited for Mission Control to begin its promised live TV feed of Armstrong starting his climb down the Lunar Module’s ladder.

It was now clear to Tom that Armstrong would take his first step onto the lunar surface minutes before the Moon rose over Parkes.

Although Parkes’s off-axis receiver might be able to pick up a TV signal a little earlier, Tom knew it would be unstable, possibly jerky, prone to drop in and out, and wouldn’t be of broadcast quality.

This meant that for Armstrong’s first step, Honeysuckle’s dish would be Goldstone’s only backup.

With mounting excitement, Tom pressed his intercom button and barked “Battle short!”, a direction to his team to let their equipment bypass safety circuit-breakers for the next crucial minutes.

After emerging from the Lunar Module, Neil Armstrong crawled backwards across a small platform he’d nicknamed ‘the porch’, towards a 2.4m ladder attached to one of the module’s landing struts.

Before taking his first step down the ladder, he pulled on a D-ring attached to a lanyard. This activated the Lunar Module’s external stowage bay, which swung out and down to reveal a small TV camera trained on the ladder.

After some adjustments to a circuit-breaker, it began filming from its upside-down position.

For a split second, what Honeysuckle’s TV technician Ed von Renouard saw confused him: “It was an indecipherable puzzle of stark blocks of black at the bottom and grey at the top, bisected by a bright diagonal streak.

I realised that the sky should be at the top, and on the Moon the sky is black, so I reached out and flicked the switch and all of a sudden it all made sense, and presently Armstrong’s leg came down.” However, at Goldstone, the TV technician mucked up his reversing switch.

After attempting to correct his error, he increased the contrast on his TV scan converter’s output, dragging most of the picture into the black, and making it very high contrast.

Still struggling, his next mistake was to adjust the focus, the result being that the photo was not as sharp.

A little while after that, he tried another setting, turning the picture to negative. This had the effect of compressing the shadow areas into white.

With each mistake, Goldstone’s TV technician compounded his problems.

In a room behind Houston’s main Mission Control room, Ed Tarkington, who was responsible for deciding which lunar TV feed to put live to air, could not understand why the pictures he was seeing coming in from Honeysuckle were so much better than those from Goldstone.

How was it that Tom’s team with their 26m dish was doing so much better than the American team with its 64m dish?

Known throughout the NASA network by his call sign ‘Houston TV’, Tarkington initially put his faith in the bigger dish and Goldstone’s pictures went live to air around the world. But it was impossible to make out what Armstrong was up to.

For almost two minutes after filming began, Tarkington persevered with Goldstone, hoping its pictures would improve. But they got worse.

By now Armstrong had reached the bottom of the ladder and was standing on one of the Lunar Module’s foot pads.

Knowing that Armstrong’s first step was imminent and that the TV feed going to air was still a mess, Tarkington made an announcement over NASA’s worldwide communication net: “All stations, we have just switched video to Honeysuckle.”

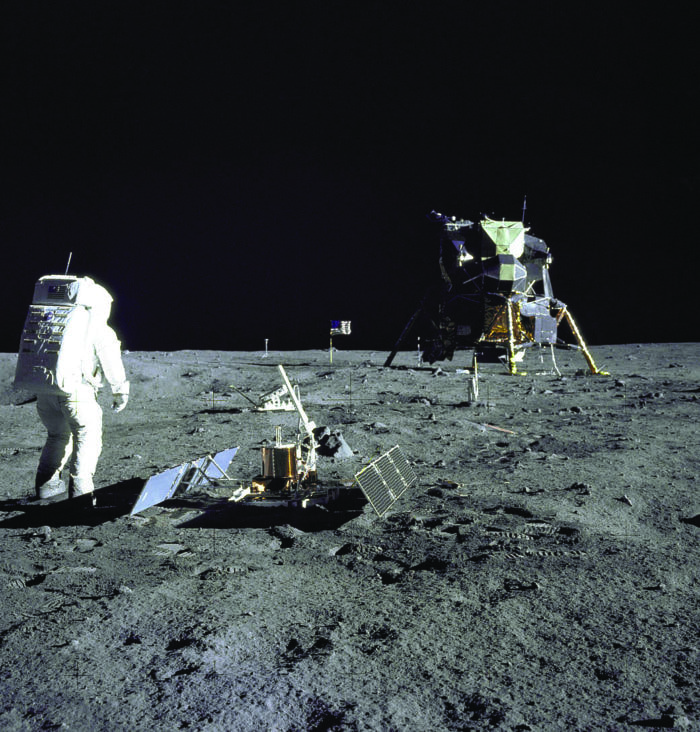

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin at Tranquility Base, the Apollo 11 team’s Moon landing site, with equipment for on-site experiments and sampling. (Image credit: NASA)

The heroes of Honeysuckle

IT WAS THANKS TO Honeysuckle that 600 million people were able to clearly see Neil Armstrong for the first time since the live feed commenced.

He held on to the Lunar Module’s strut for the next 25 seconds then, with one boot still firmly planted on the foot pad, tested the lunar dust with the tip of his other boot.

“As you get close to it,” he said, “it’s almost like a powder. The ground mass is very fine…I’m going to step off the LM now…”

A short pause in Armstrong’s voice transmission followed, during which Honeysuckle’s TV signal showed him letting go of the strut and stepping backwards to plant his left foot in the lunar dust.

It was 12.56pm at Honeysuckle when Armstrong said: “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Tom and his team had absolutely nailed live television of this unprecedented moment when a human being first stepped onto a celestial body.

For those who were privy to the telemetry streaming into Honeysuckle from Armstrong’s space suit, his heart was beating 112 times per minute, compared with Aldrin’s 81.

Honeysuckle’s live TV feed continued to air worldwide until the main signal from Parkes finally came online, more than six minutes after Armstrong had taken his first step.

From then until the end of the two-and-a-half-hour broadcast, Tarkington elected to use Parkes’s stronger signal generated by its larger dish, for the worldwide TV broadcast.

Despite the Honeysuckle team’s pivotal role in enabling the live broadcast, it wasn’t until a 20th-anniversary dinner in 1989 that Tom publicly acknowledged what he and his team had accomplished: “It hadn’t been planned that way,” he said. “But that’s the way it was. And goddamn it, we were ready!”

This story was originally published in Issue 151 of Australian Geographic. Purchase your copy here.