The wonderfully diverse world of spider silk

SPIDERS HAVE WALKED this earth since before the dinosaurs, and have been a source of fear, fascination, and inspiration throughout human history.

This has a lot to do with the wonderful webs they weave, but have you ever really thought about what they are? What they are made from or how many different kinds exist?

Australian Geographic spoke to experts from Queensland museum and the American Museum of Natural History, and whether you love them or hate them, spiders are undoubtedly one of evolutions greatest outcomes.

Different Types of Spider Silk

Silk emerges from spinnerets, which are located on the spider’s abdomen. Each spinneret has many spigots on it – hollow, hair-like silk outlets – and each spigot is attached to its own individual silk gland. Inside every spider there may be hundreds, sometimes thousands, of silk glands.

These silk glands can be grouped into at least eight categories, with each producing different types of silk for different purposes. While no one spider has all eight of these gland types, there are some with up to seven.

“Many spider silks are specialized, which means they have just the right amount of stiffness, stretch, extensibility, response to hydration, and even colour for a particular function,” said Dr Cheryl Hayashi, Director of Comparative Biology Research at the American Museum of Natural History.

“This is very similar to how we use different types of fibres and fabrics with varying attributes in our clothing.”

Seven common glands are:

- The major ampullate and the minor ampullate glands, which are used in web construction, and to form the safety dragline that spiders use to stealthily lower onto your shoulder.

- The flagelliform and aggregate glands combine to make the sticky spiral of an orb web, which is used to catch prey.

- Silk drawn from the aciniform gland is used to wrap captured prey.

- The tubuliform gland is used to make the outer silk of an egg sac.

- The Pyriform gland makes the glue-like silk used to attach the web to a surface.

While these broad classifications are true of many spiders, some like to think outside the web. This means that depending on the species of spider, these different kinds of silk can have a much wider variety of uses. These can include burrows or nests, mating, parachuting or ballooning, and some can even add colour or deceiving smells to attract prey.

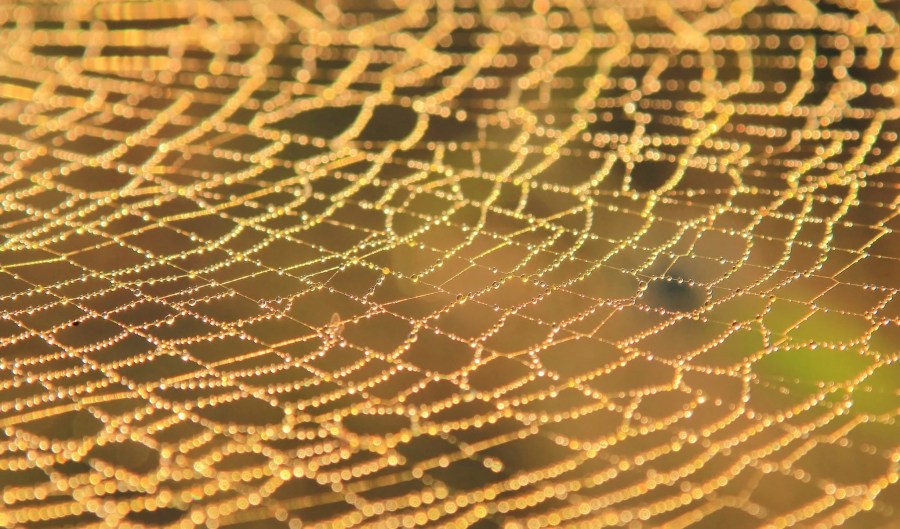

Colourful webs

Some spiders produce coloured silk or decorate their webs with strange patterns, which are designed to attract a target prey. This is commonly observed among orb-weavers.

“Some orb weavers use their silk to make different structural webs, others scent it, others colour it, like the golden orbs – that’s why they’re called golden orbs, because their web is coloured golden,” says Dr. Robert Raven, head of the arachnology unit at Queensland Museum.

“Gold is an interesting colour because it attracts insects,” said Dr Raven. As seen in Queensland Museums yellow pan trapping method for catching specimens, “if you put a whole bunch of coloured plastic plates out and put a bit of detergent on them, the gold one will get the most hits [depending on the type of insect].”

Some orb-weaving spiders that forage near flowers, such as Garden spiders, make their webs out of silk that reflects ultraviolet light or decorate their webs with flower-like patterns that reflect UV light – albeit to the human eye they just look like zigzags or crosses.

According to a study by Catherine Craig and Gary Bernard, fruit flies are two to three times more likely to fly toward a web that is reflecting ultraviolet light. So depending on the design, to an insect these webs may look like patches of open sky or mimic UV patterns given off by certain flowers.

Scuba tanks

Some marine spiders use their silk to live underwater; catching bubbles of air beneath their webs to create homemade scuba tanks.

The diving bell spider spends most of its life underwater inside a little diving bell – a bubble of air that has been collected from the surface and then anchored beneath a canopy made from silk. This diving bell can function similar to fish gills; drawing in oxygen that has been dissolved in the water.

Similarly, the Desis bobmarleyi or Bob Marley’s Intertidal Spider, seeks shelter in ‘barnacle shells, corals or the holdfasts of kelp during high tide’ where they build air chambers from silk. This “high tide low tide” inhabitant was first described by Robert Raven, Barbara Baehr and Danilo Harms of the Queensland Museum in 2017.

Seductive scents

Some spiders may infuse their silk with pheromones for to attract a mate or lure in unsuspecting prey.

Bolas spiders have a rather specific taste for male moths and have developed a unique hunting technique in order to catch them. The spider will set up a ‘fishing line’ of silk with a dollop of sticky silk on the end called a bolas; while it waits it exudes an ‘air-borne scent that mimics that used by female moths to attract males.’

Given the cannibalistic tendencies of many female spiders, some male spiders also use silk as a bit of safety net while mating.

“The male, when they’re mating, they put the line of silk across the female – called the bridal veil”, said Dr Raven. “It’s a calming thing – she senses the pheromones in the silk, and calms down with it.”

The function of this bridal veil can also differ depending on the species of spider. While a giant golden orb-weaver may use chemical-infused silk to reduce the female’s aggressive tendencies, a nursery web spider will use its silk to physically restrain the female – giving him time to make a run for it before she breaks free.

“When you develop a material that operates, evolution helps you explore potentials for that material,” said Dr Raven. Spider silk has been essential to the survival and reproduction of spiders for almost 400 million years. It has evolved to enable many widely-varying uses for spiders, and in the near future, humans will enjoy the benefits too.