Waratah: 4 things you didn’t know about the iconic flower

THE WARATAH is one of Australia’s most iconic flowers, and while it comes in many different forms, Telopea speciosissima, more commonly known as the New South Wales waratah, is the most recognisable.

With its bulbous, crimson flower head, green, razored leaves and long stem, it’s possible the waratah has adorned more Australian paraphernalia than any other flower: from stamps, all the way through to tea towels and belts.

There’s clearly more to the waratah than meets the eye, so here, we take a look at the lesser-known stories surrounding this iconic flower.

There is a white variation of the NSW waratah

When you first see it, it’s hard to believe, but yes, a white version of the iconic red waratah exists, but it’s extremely difficult to cultivate and, therefore, very rare.

Following its discovery in 1967, the white variation of the flower became known as ‘Wirrimbirra White’.

The white waratah was found in the water catchment area at Kangaloon near Robertson, NSW. Initially, the discoverer didn’t want to give up the plants whereabouts, but a well-known botanist eventually got a hold of the information.

In Gulpilil’s Stories of the Dreamtime, Aboriginal Dreamtime says that the iconic red waratah was originally white, until a wonga pigeon was attacked by a hawk and bled on the flower.

(Image credit: Jimmy Turner/Royal Botanic Garden Sydney)

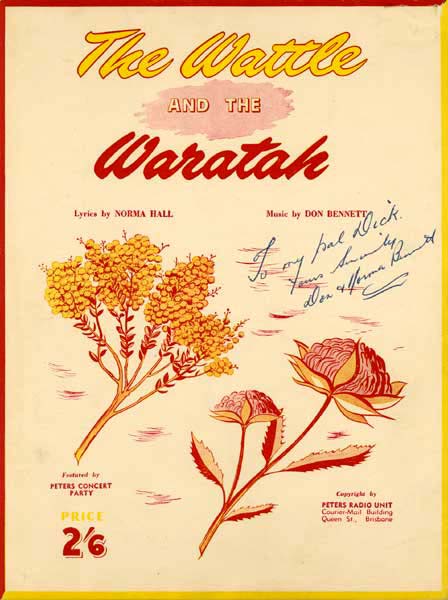

The battle for a national floral emblem: waratah vs wattle

The golden wattle officially became Australia’s national floral emblem in 1988 and in 1992 the Commonwealth Government formally designated 1 September as National Wattle Day.

However, becoming the national floral emblem of the country wasn’t a smooth path for the golden wattle.

A fierce debate over what flower should become Australia’s national emblem first erupted back in the 19th century. It’s contender? The New South Wales waratah.

Team Wattle and Team Waratah battled it out in newspapers, town halls and committee meetings, determined for their chosen flower to take out the title.

“The wattle appears rarely, if ever, to have been carved in architecture, or in applied art, or for decorative purposes… It does not lend itself to conventionalisation or design,” wrote R. T. Baker, author of The Waratah – In Applied Art and in Literature (1915), back in 1910 for the Sydney Morning Herald.

According to Bernadette Hince from the National Library of Australia, the waratah largely lost out because it only occurred across the east coast of Australia, while wattle was spread across the mainland, making it a more appropriate national floral emblem.

The waratah family is more diverse than you think

The NSW waratah may be the best-known, but don’t be fooled into thinking it’s the only form of waratah to exist in Australia. In fact, there are four other species.

Telopea aspera, more commonly known as the Gibraltar Range waratah, looks the most similar to the NSW waratah; however its leaves are slightly different in shape and placement.

The monga waratah (Telopea mongaensis), is significantly different from other waratahs in that it has long skinny leaves and no top cone, just the base flowers.

In Victoria, they have Telopea oreades, which like the monga waratah, is missing the top cone and Tasmania has Telopea truncata, a Tassie subspecies that has only a few red flower heads that clench inwards.

The Tasmanian waratah. (Image credit: JJ Harrison/Wikimedia)

The waratah in the arts and crafts movement

The arts and craft movement first began in Britain in the mid-1800s, which historians argue was a rebellion against mass produced goods, in favour of intricate, handmade products.

The movement quickly made its way to Australia at the end of the century and the waratah began featuring heavily in these applied arts, because the movement happened to collide with Australia’s bid to cultivate a national identity in the lead up to and after federation.

Collections from the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences shows the waratah depicted on leather book bindings, sheet music, stained-glass windows, vases, wall tiles, and cups and saucers.

One Australian-French artist, who, like R. T. Baker, was on Team Waratah, went a step further, depicting the waratah on statues, buildings and interiors. He was also behind the stained-glass windows in the Sydney Town Hall of goddess-like women, surrounded with waratahs.