Gore into art: Meet the female taxidermists working in our museums

WHEN ‘TAXIDERMY’ IS mentioned, certain images of men in camouflage bearing large hunting knifes are often evoked.

The idea of taxidermy largely stems from shows we watch where taxidermists are burly hunters who proudly mount deer heads on the walls of their home or disturbed individuals that relish in animal cruelty.

But the truth is, there’s another world of taxidermy out there that you’re far more likely to encounter in Australia and where women, not men, seem to dominate: the museum.

In fact, at the Australian Museum in Sydney, the first woman to gain employment was taxidemist Jane Tost in 1864. She later went on to create a popular taxidermy business with her daughter, Ada, and won various medals for her craftsmanship.

Here, we spoke to two female taxidermists about some of the grizzlier parts of the job and how they found their way into the field.

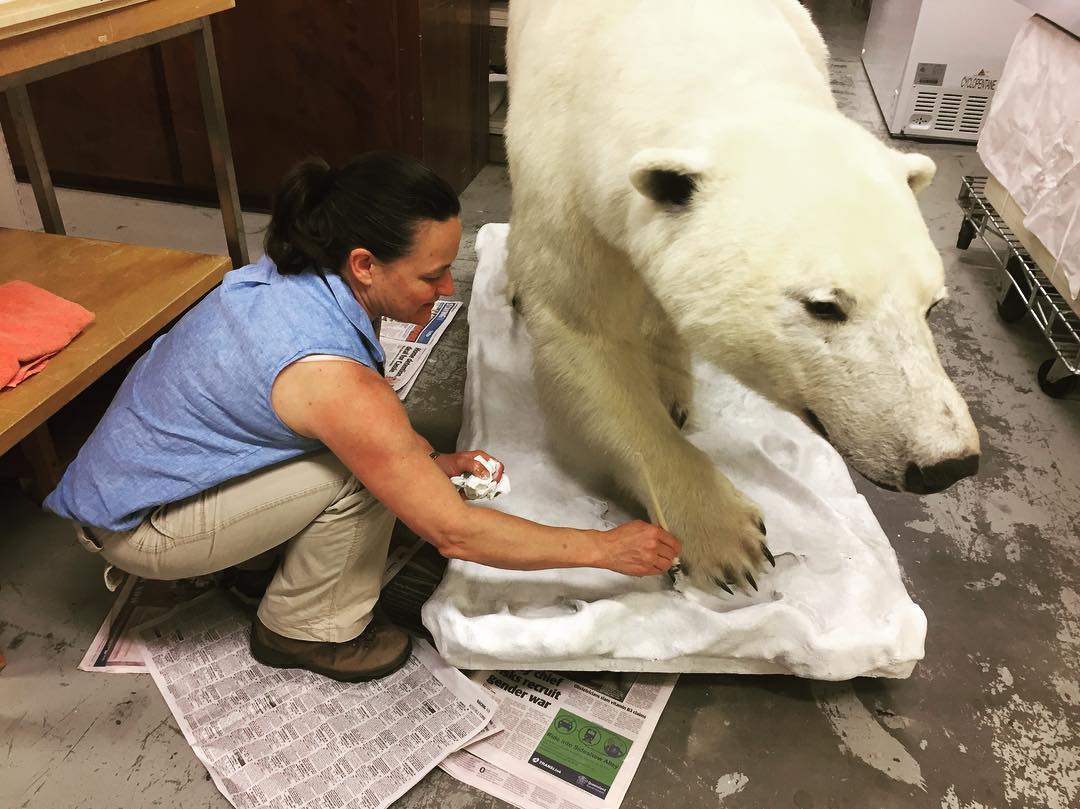

Alison Douglas, taxidermist at Queensland Museum

Favourite taxidermy: Possums

FOR ALISON Douglas, senior preparator and taxidermist at the Queensland Museum, taxidermy was the combination of all the things she loved: animals, natural history, science and art.

Alison describes herself as first and foremost a visual artist and taxidermy as just another form of art; albeit a grizzly one.

“I was never repulsed, but it is pretty graphic,” Alison admits. “People can’t quite believe that you get the dead animal and you do the entire process from skinning it to putting it back together and looking realistic.”

The gore, Alison explains, is actually just a small part of the process.

“If the animal’s fresh and in good condition, there shouldn’t really be much gore,” she says. “[The animal] skins quite cleanly and then, once you’ve discarded the body which comes out all in one go, you’re just working with a skin, which is more like a textile or upholstery job.”

Alison then begins the process of tanning the animal’s skin while she sculpts the body from wood shavings and other natural fibres, using photographs and drawings of the animal’s muscular system to figure where it all goes.

Once the sculptural reproduction of the animal is finished, she grabs the skin and pulls it over, stitching it all up.

After she pops in the correct glass eye from her “drawer full of glass eyes”, her work, which can take anywhere from one day to weeks, is complete.

But before you jump right in, she cautions those who want to start experimenting at home with dead animals you come across.

“It is really difficult in Australia because what you can do is so limited by the laws that cover native animals,” Alison explains. Australia’s laws around taxidermy are so strict, in fact, that you can be penalised with some hefty fines for performing taxidermy on native wildlife without a permit.

“You can’t even pick something up from the side of the road,” Alison adds.

While Alison’s had a long career in the field and is one of the few museum taxidermists around Australia still operating, she’s found that sometimes her expertise is questioned due to her gender.

“I think there’s a difficulty in being seen as an expert,” she confesses. “I’ve found that people might not appreciate my level of experience and ability, but I have found recently there’s a very supportive international network.”

Despite some adversity, she maintains that women do rule the modern world of museum taxidermy.

“Some of the people who are the most-followed and highly respected within that museum taxidermy field, internationally, are women.”

In fact, Alison believes that many of the people interested in taxidermy today are young women. Unfortunately, however, with so few positions available in museums, young taxidermists will most likely have to turn to commercial pathways like pet taxidermy. But, she doesn’t think that should deter anyone from trying something new and offbeat.

On top of this, Alison explains that museums sometimes underestimate the public interest in taxidermy but she argues that they will continue to play a vital role in the ecology of any museum.

“As an educational resource, it’s really amazing and particularly, if you’re allowed to touch the animal too, there’s nothing that really replaces that real contact,” she says.

“The alternative is a photograph but there’s nothing really like the real thing.”

Kirsten Tullis, taxidermist at Western Australian Museum

Favourite taxidermy: Birds and bats.

DESPITE COMPLETING a degree in biology back in the early 80s, Kirsten’s career path steered her towards taxidermy.

While volunteering at the Western Australian Museum in 1981 she met Ron Johnstone, an ornithologist, who taught her how to prepare bird skins for study. Just a year later, she was offered the role of Assistant Preparator.

“I enjoyed dissecting things at university and had already started preparing a series of bird skulls as a hobby,” Kirsten says nonchalantly.

“I love animals, and while I usually feel detached enough not to feel sad when working on one that has died, I often think about what they did when they were alive.”

Now a senior preparator, Kirsten’s job isn’t limited to just taxidermy, she also prepares the museum’s elaborate displays.

“One day I might be mounting a bird and the next, modelling a creature or plant from scratch or moulding, casting, painting a model, or cleaning out and mounting a few crustaceans,” Kirsten says.

But it’s her work in taxidermy that is most impressive. Kirsten clinically describes the process of turning a dead bird into a lifelike display.

“I make the first incision from the top of the breastbone to just above the tail, and begin separating the skin from the body,” and she then carefully peels the skin off the bird’s body, removing all the muscles and fat and separating the skull.

After creating the form of the bird with natural fibres, wires and string, the dried skin with feathers is pulled back over and the finishing touches made after the taxidermy has dried for around one week.

After being in the field for 36 years, Kirsten hasn’t faced any adversity for being a woman, despite what was a bit of a boy’s club in the 80s. Now, she says that more females are getting involved than ever before.

“Taxidermy was definitely male orientated in the past, but I don’t think it is so much now.

“Over the years I’ve taught [lessons in taxidermy to] around 25 people, mainly in bird taxidermy, and at least half were women.”

Like Alison, Kirsten believes that taxidermy will always be useful and capture people’s interests.

“We have a few older mounts in the collection of extinct animals, so these are especially important”

“[But also] it gives visitors a chance to see animals up close either in a display of their own or within a diorama or recreated natural scene.”

READ MORE: