The dangers of heatstroke

HEATWAVES KILL MORE Australians than any other natural hazard. While dramatic disasters like floods, bushfires and cyclones dominate the media, extreme heat is a silent killer taking the lives of some 500 people every year. In the last 100 years, at least 5,000 people have died as a result of heatwaves and heatstroke. More than 200 people died in the January 2014 heatwave in Victoria alone.

While death rates are declining, experts warn that the risk posed by severe heat is increasing. Heatwaves are becoming longer, more frequent and more intense with climate change. Anyone can succumb to the heat, but the elderly, the very young, those who work outside, and those under stress are particularly at risk. As Australia’s population ages, grows and urbanises, the number of people at risk of heat stress will continue to rise.

RELATED: Dr Karl: Killer heatwaves, global trend

THE MURCURY’S SOARED above 40°C and a volunteer firefighter is facing the fury of a bushfire in full flight. He’s been on the go for hours, dressed from head to toe in heavy clothing, and hasn’t been taking in the huge volumes of fluids he needs. Suddenly, he collapses. His mates drag him from the fire’s path and race him to intensive care paramedic Jason Watson, of the Ambulance Service of NSW, waiting just behind the frontline.

“He was unconscious, his skin was hot, but he was quite dry – he’d gone beyond sweating,” Jason says, the incident still sharp in his memory years later. Within minutes, the fireman began having seizures, his brain struggling with internal temperatures above 41°C. “We rolled him on his side, sought to protect his airways, provided intravenous fluids and put cold packs on the neck, armpits and groin – where the blood vessels are closest to the surface of the skin.”

He was rushed to hospital and lived – among the fortunate few to survive such serious heatstroke. “I’ve been an ambo for 29 years and I’ve only seen that one fair-dinkum case of heatstroke,” Jason says.

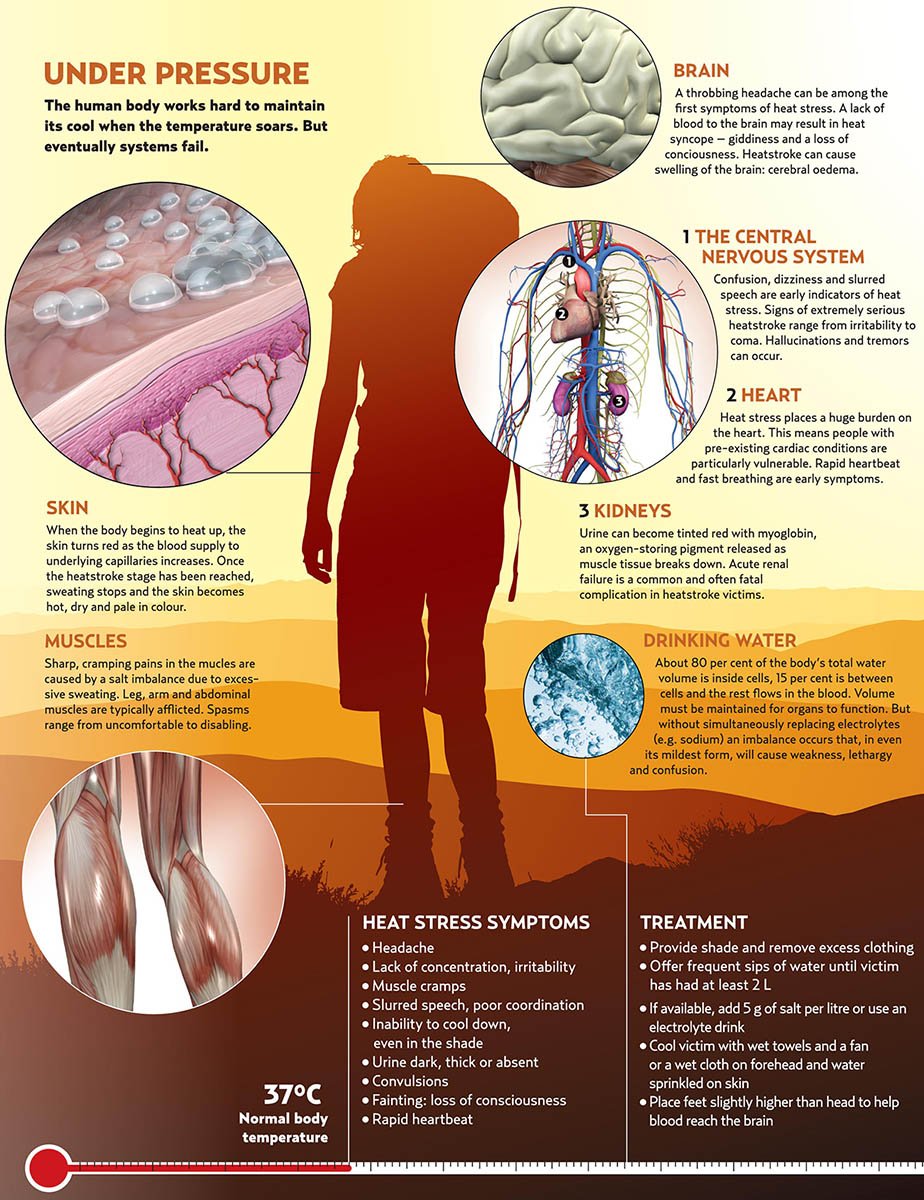

Push human bodies beyond their normal temperature (about 37°C) for long periods and they buckle and break. Our thermal regulation systems can maintain that temperature efficiently but infection or external factors such as extreme heat, a high physical workload (such as marathons) and dehydration can overcome the body’s ability to deal with the extra heat. Enzymes cook, impeding vital processes, and organs shut down.

Heat stress can be mild, causing dizziness and headache, but at its most extreme, heatstroke is fatal in up to 80 per cent of cases, the patient often suffering unconsciousness and cardiac arrest.

Click to enlarge in a new tab.

Heat stroke: the silent killer

Our country’s abundance of extremely hot conditions makes this a real risk. Schoolboy David Iredale, who died in 2006 after becoming lost and severely dehydrated in the Blue Mountains, NSW, is one recent tragedy. Aboriginal elder ‘Ribs’ Ward, who succumbed to 50°C heat in a paddy wagon while being transported from Laverton, WA, in 2008, is another.

Children that are left inside cars in warm weather can also die from heatstroke. Survivors may suffer serious permanent damage to the brain and other vital organs. Usually the human body deals with extra heat by sending more blood to the skin, where additional capillaries open, increasing the blood’s exposure to a cooler external temperature. This is why we turn red when exercising. Additionally, the body begins producing sweat, which, as it evaporates, cools both the skin and the blood in the underlying capillaries.

Factors impeding these natural cooling systems include ambient temperatures above 37°C, which heats rather than cools blood sent to the skin; high humidity, which reduces cooling by evaporation; and dehydration.

Dr Veronica Miller, a lecturer in the School of Public Health at Perth’s Curtin University of Technology, has studied heat’s effect on outdoor workers in the Pilbara and labourers in the Middle East. Like water in a car radiator, she says, the body’s internal fluids convey heat via the blood to the skin, away from vital organs. “If you lack water, you’re less able to dissipate the heat,” she explains. But the more you sweat, the less fluid is available within the body to maintain that internal radiator. Drinking water at this stage might help keep pace with what you’re losing in sweat, but it won’t make up the difference if you were dehydrated to begin with. And Veronica’s research shows most Australian mineworkers start shifts with not nearly enough water in the tank.

“The majority of workers [studied] were found to be inadequately hydrated at the start of the shift and their fluid intakes in general were well below the requirements to replace sweat losses,” she says. Up to half were considered severely dehydrated when they started the shift. “Drinking water is just not part of the Australian culture. [The workers will] drink beer the night before and a cup of coffee before they start the day.”

Also, in humid environments with no airflow, as in many mines, sweat doesn’t cool the body. “Sweat that runs or drips off you isn’t doing anything at all – it’s just depleting you of liquid,” Veronica says.

Cause of heat stroke

Dr Graham Bates, who is an adjunct professor at both Curtin University and the Faculty of Medicine at the New Zealand University of Otago, says liquid that miners can lose in a shift (up to 8L a day) makes them susceptible to heatstroke. Hundreds are affected annually by heat-related illness. They might regain up to 2L a day from the food they eat, but still have a daily 6L water deficit. “Imagine if you have to drink 6L a day – day in, day out – you just couldn’t do it,” he says.

Graham, who also works with high-level sportspeople such as Western Force rugby players and international cricketers, says athletes can lose up to 3L an hour in hot conditions. The low-salt diet of elite athletes can also cause problems. Salt in body tissues acts like a magnet, drawing water from the gut to hold it where it’s needed. Insufficient salt can cause muscle cramping, inability to retain water and even death. Most people get enough salt from a normal diet. But athletes who sweat a lot or workers who wait more than three hours between refreshment breaks may need an extra supply: electrolyte drinks.

“I advised a female veteran world-record holder for 10 and 15 km runs,” Graham says. “She used to get dreadful headaches when she finished. She was very health conscious and didn’t put salt on her food. That was the cause of her problem: she wasn’t having enough salt, so couldn’t retain the water.”

In the early stages of heat stress the body will continue to try cooling itself down. The main treatment is to provide the patient with fluids and cool their body with wet towels and fans. Ice or iced water on the body can have a detrimental effect by causing surface capillaries to close.

But if the person deteriorates, their body shuts down everything, even sweating, to protect their most vital organ. “When [heat stress victims] go from red to white, you’re buggered,” Graham says. “The body is saying, ‘I can’t afford to send any more blood to the skin, I need to send it to the brain’.”

This is an edited version of an article originally published in Australian Geographic Jan–Mar 2010.

READ MORE:

- Dr Karl: The growing trend of heat waves

- Koalas hug trees to keep cool

- This is what happens to your skin when you get sunburnt