When is it going to snow?

AUSTRALIA’S SNOW SEASON is notoriously fickle. Some years bring deep cover lasting for nearly six months (such as in 1964). Others barely cover the grass for a few weeks (such as in 2006).

The difference between a good season and a bad one may be a single weather event, such as the so-called Snowmageddon in 2014, which dropped around a metre of snow in less than a week.

The high variability of the snow season means the Bureau of Meteorology doesn’t currently produce a seasonal outlook for snow (as we do for temperature and rainfall). However, we know that the same climate drivers that affect Australia’s weather also influence our snowfall.

El Niño and La Niña

The best way to see how snowfall varies from year to year is to use data from Spencers Creek in the New South Wales Snowy Mountains, a pristine site 1,830m above sea level. Past studies show that these data tend to correlate with snow more generally across the mainland alpine regions, but they don’t always match the cover at lower elevations.

First, let’s look at El Niño. We are coming out of one of the strongest El Niño events on record. During El Niño years, rainfall is typically below average across eastern Australia during the snow season, and temperatures are warmer during the day. The maximum snow depth averages about 35cm less than the all-years average, while the period with more than 100cm is about two weeks shorter.

El Niño’s opposite, La Niña, usually brings above-average rainfall, but this doesn’t necessarily mean more snow. Temperatures can sometimes be too high and hence precipitation may fall as rain even at higher elevations, which can actually decrease snow depths.

This has happened more frequently in recent decades as a result of climate change. Seven of the past eight La Niña years have produced lower maximum snow depths than average.

Historically, neutral years have had more consistent good snow depths than either El Niño or La Niña years.

It is important to consider these drivers as tilting the odds towards a particular outcome, rather than guaranteeing it. While about half the historical El Niño years have had well-below-average snow, three El Niño years had well-above-average snow depths: 1972, 1977 and 1991. That said, no recent El Niño year has produced good snow, with these winters tending to be particularly dry.

Maximum snow depths for all years 1954-2014, segregated by a) ENSO, b) IOD and c) SAM. (Image: Australian Bureau of Meteorology, Author provided)

Average snow depths throughout the season, with 90% confidence interval shaded, segregated by a) ENSO, b) IOD and c) SAM. (Image: Australian Bureau of Meteorology, Author provided)

The other players

To make things more complicated, El Niño and La Niña don’t act alone.

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) may actually be a clearer indicator of snow depth. Similarly to El Niño, positive IOD years tend to be drier than average across southeastern and central Australia, leading to lower snow depths. They are particularly dry over the Australian Alps when El Niño and positive IOD events coincide.

Unsurprisingly, snow depths in late winter and spring are also lower when the IOD is positive. Snow depths are generally higher than average during years with a negative IOD.

The Southern Annular Mode (SAM) has the strongest relationship with snowfall. Cold fronts and low pressure systems are the main weather systems that bring our snow, and the SAM indicates whether the westerlies that bring this weather are closer to Australia or the poles.

Negative SAM brings the fronts, rain and snow further north, while during a positive SAM these fronts move further south. The average (mean) maximum snow depth in negative SAM years is a cool 240cm, almost 80cm higher than in positive years. Unfortunately, accurate forecasts for SAM are still only possible for two to three weeks ahead, which means that this measure is more of a diagnostic rather than a forecasting tool.

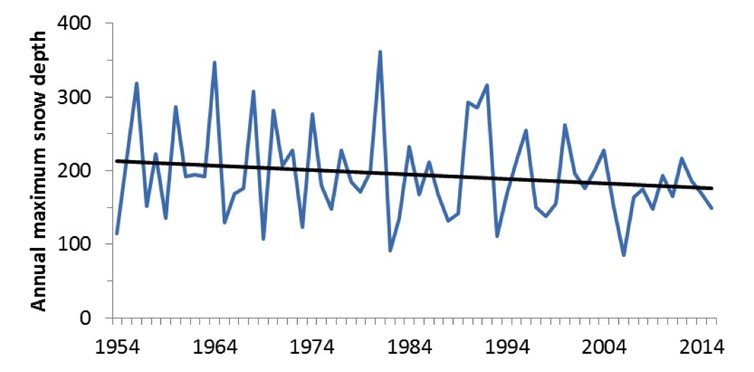

Of course, climate change also plays a role. Both maximum snow depth and total snow accumulation have declined over the past 25 years. The reduction in snow cover is most obvious at lower elevations and at the end of the ski season when warm spring rains can hasten the melt.

However, while it has been a few decades since the last 3m year (in 1992), there are still above-average seasons when the weather and climate is right, most recently in 2012.

Annual maximum snow depth at Spencers Creek, 1954-2015, with a linear trend line shown. (Image: Australian Bureau of Meteorology)

Less moisture? Never fear, snowmaking is here

El Niño, positive IOD and positive SAM periods all typically lead to less moisture in the air, which partly explains the lower snowfalls. But with less cloud to trap in the heat at night, they also have lower minimum temperatures.

Luckily for snowriders, these are also the ingredients for good snowmaking and can contribute to less snow melting. The ability to harvest snow and move it where needed can also allow ski resorts to moderate the impacts of average or below-average natural snow cover on skiers and snowboarders.

What’s ahead in 2016?

While forecasts for the Southern Annular Mode only have skill for a few weeks ahead, and it’s also too early to forecast what may happen in the Indian Ocean, we can look to the Pacific.

The 2015 El Niño is in decline and neutral conditions are expected to prevail by winter. For 2016, the most likely outcomes are either neutral or La Niña conditions, a hopeful early sign for 2016 snowfalls.

Finally, a word of caution. Don’t get too excited by early snowfalls, or indeed sell your skis if winter starts with no cover: two of the best seasons on record – 1956 and 1981 – had no snow at all at the start of June, while two of the poorest seasons – 2006 and 1965 – had 20cm and 60cm, respectively, of snow on the ground before the Queen’s Birthday weekend. Early-season cover isn’t always the guide we might think it is.

While we know the Australian snow season can certainly have large variations in its snow cover, knowing the state of Australia’s climate drivers can give a heads-up on what the season may be like. But remember, there are always exceptions to the rules.

For the most up-to-date information on climate drivers, check out our ENSO Wrap-Up. Read further analysis here.

![]()

Catherine Ganter, Senior Climatologist; Acacia Pepler, Climatologist; Andrew B. Watkins, Manager of Climate Prediction Services; Blair Trewin, Climatologist, National Climate Centre, and David Jones, Scientist; all from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.