Legend of the deep: Ron Allum

RON ALLUM, LIKE the deep oceans where he often works, doesn’t give up his secrets easily. He’s averse to the kind of hyperbole that’s so much a feature of the US movie industry in which he’s spent the best part of a decade.

But this former ABC radio engineer’s inventiveness and technical know-how was instrumental in the record-breaking exploration of one of the planet’s last frontiers on 26 March 2012.

That was when James Cameron piloted a revolutionary submersible to Earth’s lowest spot, the floor of the Mariana Trench, known as the Challenger Deep – 11km beneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean.

Brains behind Deepsea Challenger

Ron was no stranger to deep, dark and dangerous realms when he was first invited to work with James Cameron, rigging cameras for a series of oceanic documentaries back in 2001.

He’s a legend in Australian cave-diving circles and was notably a member of the 1988 Australian Geographic Society (AGS) sponsored caving expedition that became trapped underground by a rainstorm that hit the usually arid Nullarbor Plain (AG#19).

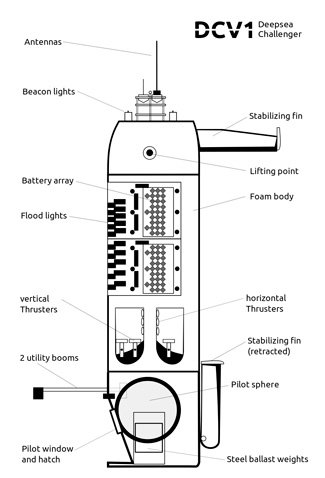

Schematic of Deepsea Challenger (Credit: Deepsea Challenge/Zuckerberg)

Water cascaded into the sinkhole, flooding the cave and causing a rockfall that trapped 13 cavers, Ron among them. Prior to the drama, he had rigged up a two-way radio system that could transmit through solid rock, as long as the transmitter and receiver were vertically aligned and switched on simultaneously. Despite the precariousness of their situation, at the daily scheduled time Ron calmly radioed in, establishing communications with the rescue party. This enabled the identification of an escape route.

RELATED: Deepsea Challenger sub an Australian marvel

Ron’s reputation for composure under pressure has earned him the respect of those who’ve worked alongside him, among them AGS award winner Dr Glenn Singleman, medical officer aboard the recent dive and on another ambitious James Cameron project in 2005 – a live broadcast from the wreck of the Titanic.

Getting to the bottom of the Mariana Trench

“He’s an incredibly competent person both on a technical and personal level,” says Glenn. “I worked with Ron…on the Titanic Live project where Jim [Cameron] really came to trust Ron’s engineering ability.

There were problems that most people couldn’t solve…to beam a signal live from 12,500ft [3810m] down into the living rooms of America was an incredibly bold thing. Jim charged Ron with developing what it took.” Ron created a system of 12 sea-floor cameras to transmit pictures to the surface via fibre optics.

Shortly after this, James asked Ron to start work on the technology to get to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. For the first few years Ron carried out small-scale component testing in the laundry of his modest terrace in Sydney’s west, including work on the all-important central sphere.

“It’s where Jim sits and pilots the sub…it took two years to design and make. We had lots of teething problems… None of us had designed a pressure sphere before,” says Ron.

The pressure sphere was one element of the craft that would eventually be named Deepsea Challenger. The cigar-shaped sub was revolutionary in every way.

“Subs spend a lot of time going up and down the water column and the depth was so great that we were going to be doing a lot more vertical travel than horizontal,” says Ron of the sub’s unusual upright configuration.

Deep ocean work

Weight had been an issue with earlier Russian submersibles chartered for deep ocean work by the Cameron team, and it was in this area that Ron made his biggest breakthrough. He developed a new type of syntactic foam that would form the chassis and provide flotation for the sub, eliminating the need for a heavy framework for mounting of filming and lighting equipment. Existing foams weren’t suitable, so Ron’s breakthrough product, the result of meticulous research, has since been patented by him and James.

Ron piloted the sub on the expedition to capture extra footage of the trench, although the deepest dive was reserved for James. “I did get to do one of the best dives of the expedition…through this incredible seascape where I got to fly across the face of an incredible escarpment,” he says.

He now plans to make the technologies available to others who wish to explore the ocean’s depths. His quiet competence has the ability to inspire others, as Glenn explains: “Everyone who works with Ron is inspired by his humility and his genius. Every time there was a moment when we wondered how we were going to get out of this, Ron would come up with some answer and everyone would just look at him and go ‘wow’.”

This article was originally published in Australian Geographic September-October 2012 edition (AG#110).

RELATED STORIES:

- VIDEO: Surreal deep sea jellyfish near Mariana Trench

- Aussie engineer world’s deepest solo dive

- James Cameron interview: the world’s deepest dive