Dinosaur discoveries: The dinosaur musterers

IN FEBRUARY, WAYNE RHODES was patrolling Sandhills, his drought-stricken property near Richmond in central Queensland, when he noticed something strange near the Flinders River. “I was just driving around checking the grass to see if I had any left, because there was still a drought,” Wayne says. “I looked down towards the riverbank – I don’t really know why – and there was this fossil sitting there. I thought I had a snake at first because of the shape of it – and it still seemed to have the skin on it.”

The grazier and sometime plumber had discovered the perfectly preserved, fossilised head of an ancient turtle – an incredible find. What Wayne thought was snakeskin was the pattern of the scales.

Straight-talking Wayne wasn’t even keen on fossils until he heard about some big dinosaur discoveries on a nearby property in 1989. “I’ve been out here for 37 years, but I didn’t know fossils were here until the big finds were made,” he says. “Up until then, I was just interested in riding horses and keeping cattle. Now I’m that excited to find them.” He pulled in his first big one in 2004: a 3m, long-extinct fish, new to science and subsequently named ‘Boofhead’.

For more than a century, important fossils have been plucked from outback Queensland’s dusty soils. Farmers in the Winton, Richmond and Hughenden areas so regularly find such treasures that palaeontologists have dubbed the area the ‘Dinosaur Triangle’.

Thanks to a recent surge of interest in fossil-hunting, Queensland has gained a reputation as Australia’s dinosaur hotspot. This palaeontological renaissance has brought both a new understanding of Australia’s ancient past and a curious alliance between farmer, scientist and field volunteer, united in a common passion for digging up ancient history.

Dinosaur fossils in Queensland’s outback

Two huge discoveries, a little over 15 years ago, helped kick off the current passion for dinosaur hunting. They were both on Marathon station, a 22,662 ha cattle and sheep run between Richmond and Hughenden.

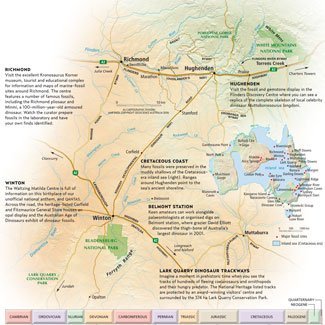

The dino trail View Large Map

For close to 40 years Marathon has been home to the Ievers family and they’re used to finding bits and pieces of ancient fish and other fossils while working the property. But nothing had prepared them for what they found in 1989.

Late one afternoon, Rob – then 35 – and his brother Ian were mustering cattle about 500m from the homestead. The brothers were on motorbikes and Ian broke away to ride up a dry creekbed. He saw something sticking out of the bank and, thinking it might be a bit of fossil wood, gave it a kick. It felt unusual so he picked up the 15cm long piece that had broken off and wiped it clean. There in his palm was a perfect line of interlocking teeth formed into the shape of a snout.

A stub remained where the piece had broken off. Ian called Rob and the two began scratching the crumbly, dry shale soil from around it. To their amazement, they could see more teeth disappearing back into the bank.

Night was falling, and they had to leave their discovery until the following morning. They returned with their mum’s garden tools and kept digging.

“We could plainly see it was a skull – further back we could see vertebrae connected to the head,” Rob says. “By this stage we were 1.2m back into the bank. We realised it was very significant but we didn’t have a clue how to take bloody fossils out of the ground, so we called in the Queensland Museum.”

A team led by Dr Mary Wade was assembled and on site within a week. After three days an almost complete pliosaur – a 5m marine reptile from the Cretaceous period – was pulled from its 100-million-year-old grave.

“When we got it out, you could see it had been lying on its back, just like this thing had rolled over and died yesterday,” Rob says.

Three months later, while mustering sheep, sharp-eyed Ian noticed another strange rock that looked like an ankle bone. It turned out to be the best specimen so far found of Minmi, a 2.5m armoured dinosaur unique to Australia.

“We couldn’t believe it – in the space of three short months we’d found two world-class fossils on the place,” Ian says. “Everyone was so surprised at what happened. If you’d said to me back then that you’d find a fossil in outback Queensland I’d have said you had rocks in your head!”

Rob was so impressed by what was found on his property that he began setting up a fossil museum in Richmond to give the pliosaur and Minmi a home. The Richmond Marine Fossil Museum, part of the Kronosaurus Korner complex, opened in 1995. Since the museum opened, the local landowners have had their eyes opened to what could be found in their soils, and they’re now clear on what’s a rock and what isn’t.

In Queensland all fossils are technically the property of the State and a licence is needed to collect them. Rob says some landholders who find fossils misguidedly fear the Government will take away their land, so donate fossils to the museum anonymously. “My land wasn’t resumed and we had some of the best fossils in the world found on our place,” he says. “Fossils are pretty widespread in Richmond so land is unlikely to be resumed. I tell you something though: if the Government did resume anyone’s land, you’d never find another fossil on anyone’s property.”

Rob suggests that anyone finding a fossil anywhere in Australia should ring their State’s main museum and ask someone to come and have a look. The value of the fossil may be tax deductible if you donate it to a museum.

Rob says whenever he’s out mustering these days he has one eye on the cattle and the other on the ground looking for the next big find.

Pre-historic obsession

Since Winton grazier Dave Elliott found a thighbone of Elliot, Australia’s biggest dinosaur (A giant awakes, AG 65), the extinct reptiles have taken over his life. Although he’s still trying to run his grazing property, Belmont station, the bulk of his time is spent organising digs and planning the permanent Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum of Natural History, which will hopefully open in Winton in the next few years. “It’s pretty full-time work, eh?” he says. “I don’t have time to do any property work – I’m making a pretty poor fist of it at the moment.”

On days when he is working Belmont, he invariably finds more fossil sites. “On Boxing Day last year I was blocking up a mob of Brahmans on a four-wheeler, just settling them down. And just as I drove off, I looked at the ground and saw an arm bone of something as big as Elliot. I’d been sitting next to it for 10 minutes and hadn’t noticed it.” Short on space to store the growing number of priceless fossils taking over his homestead, he put the metre-long specimen on an old door, which he laid on a spare bed.

Queensland Museum runs organised expeditions to continue searching for more material on Belmont, and so far several ute-loads of fossils have been transported back to the museum in Brisbane, including teeth from carnivorous dinosaurs, bony plates from crocodiles, parts of turtles and fish, and the wings from 100-million-year-old moths, cockroaches, dragonflies and beetles.

Queensland- Australia’s dinosaur capital

Queensland is Australia’s premier dinosaur graveyard, according to Queensland Museum senior curator Dr Alex Cook. “For one thing, two-thirds of the State are covered by Cretaceous rock,” he says. “This dates back to between 90 and 130 million years ago, the period during which dinosaurs roamed Australia.”

Alex says the large amount of broad-acre agriculture and grazing helps expose the fossils. “When you muster sheep on bikes, you are close to the ground so you pay more attention and tend to notice anything unusual… There’s some Cretaceous rock in WA, and footprints have been found, but why big dinosaur fossils haven’t also been found there is the $64 million question. Is it lack of looking? Is it too much weathering? Who knows?”

In the middle of the ‘Age of the Dinosaurs’, some 120 million years ago, the whole continent of Australia was sucked down by tectonic activity and water poured in from the north, flooding much of what is now western Queensland and parts of the NT, SA and NSW. This shallow inland sea, with an average depth of 50m, persisted for a few tens of millions of years, providing a home for fish, turtles and marine reptiles. The floor of this ancient sea was carpeted with their remains – the fossils we find today. Occasionally the carcass of a dinosaur that had lived on the land would be washed into the sea, where it would sink and endure through the aeons alongside the remains of marine creatures. This was what happened to the Minmi found at Marathon.

As Australia drifted north, the whole continent began to gently rise again and massive river systems to the south spewed immense quantities of sand and silt into the dwindling inland sea. These formed extensive delta systems: complex habitats that preserved the remains of both estuarine and riverine animals such as crocodiles (see box above), marine reptiles and a wide variety of fish, along with land-dwelling dinosaurs such as Elliot.

It was in the sediments of these deltas that dinosaur footprints also became fossilised, such as those at Lark Quarry, 95km south-west of Winton.

Paleontology passion

Six years ago, Kylie Piper was sitting among strangers in the back of a Land Rover, driving along in the dead of night in outback Queensland. She had no idea where she was going. All she knew was she was off to find fossils – she’d travelled from her home in Sydney to volunteer at a new dig site. But where it was and exactly what was there were being kept a dark secret to prevent fossil thieves from ransacking the site. As Kylie – a self-confessed dinosaur nerd – and her companions discovered, the secret turned out to be enormous: it was the excavation of Elliot, Australia’s largest dinosaur.

Kylie has now been to the Elliot dig three times, in 2002, 2003 and 2004. “Basically I have a dinosaur fetish,” Kylie, 30, says. “I like all of them, the bigger the better. All my friends think I’m very strange, especially as the dig is always in the middle of the ski season. While everyone else is heading south, I’m heading north to Queensland!”

Kylie’s fascination with science has led to her job as a science communicator at the Australian Museum. She says she chases dinosaurs in her spare time the same way some people chase storms. “The first year I was there I staked out a small area of a few metres and I called it Kylie’s Corner… I didn’t find much the first two years, so by the third year I went for the whole two weeks – I was determined to find something and I wasn’t going to leave until I did. They couldn’t get rid of me!”

After many days of digging, she stumbled across something that turned out to be a vertebra from a long-necked dinosaur, one of the largest examples found anywhere in Australia.

The slow dinosaur dig

Jo Wilkinson exhumes dinosaurs from their stony coffins. During her painstaking work as a senior technical officer with the Queensland Museum over the past 14 years, she’s spent up to two months preparing a single piece of bone.

“You’re working millimetre by millimetre,” she says. “I put my headphones on, look down the microscope and just get lost in it all. It’s a bit like being a jeweller – there’s the fine detail, and you are slowly revealing something and you are the first person to see that thing.”

But what really intrigues Jo is taphonomy, the science of trying to work out what happened to the animal before and after death, including processes such as weathering, transportation and scattering. For example, a bone found with its most bleached side down might have been flipped over by a scavenging animal some time in the distant past.

“When I’ve been working in the lab for a couple of hours, those questions become very big, such as ‘I wonder whether you’re male or female? How did you die? How old were you? Did you die a fearful death?’” Jo says, with a gleeful smile. “You bond with a specimen after a while.”

Abbie Thomas and Paul Willis are science reporters with the ABC. Their recently released book Digging up deep time is a road trip through the evolution of life in Australia.

Steve Salisbury and Australian Geographic thank Ian Duncan, Isisford Shire Council and other members of the Isisford community for their assistance during fieldwork. Research was funded by the Australian Research Council and the University of Queensland, in association with Isisford Shire Council, the Queensland Museum, Land Rover Australia and Winton Shire Council.

Source: Australian Geographic Jul – Sep 2006

RELATED STORIES