In early September 1922 a group of astronomers sailed to an isolated beach in the Kimberley, set up camp behind a row of sand dunes, and soon made history.

On 21 September they proved Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.

But for such a significant moment in science, surprisingly very few people know much about it.

So, to mark the centenary of the event, it’s time to take a look back at the incredible story of the Wallal Expedition…

What was the Wallal Expedition?

The full name, Wallal: the 1922 Solar Eclipse Expedition to Test Einstein’s Theory, says it all.

In 1915 Albert Einstein had published his Theory of Relativity, arguing that gravitational objects experiencing gravitational pull warped space-time around them. Essentially, he said space was curved.

Up until this point, Isaac Newton’s understanding of ‘absolute space and absolute time‘ was accepted as fact. Scientists believed space was rigid.

However, Einstein’s theory was just that – a theory. And a controversial one. Seven years later it was yet to be proven.

Top scientific minds from across the globe had worked together to surmise the best way to prove the theory would be to witness and document light from a distant star bending as it entered the Sun’s gravitational field.

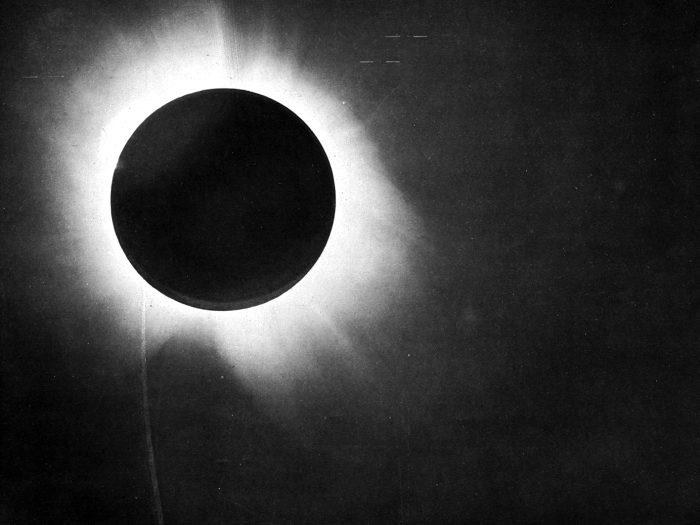

But although cameras existed at the time that could capture light beams, the overwhelming light of the Sun made photographing them impossible.

It was concluded that capturing these images during a total solar eclipse would be their best chance.

Multiple attempts by different scientists were made – the most notable in 1919 when a British team led by Sir Arthur Eddington observed and recorded the bending of star light during a total solar eclipse just off the west coast of Africa. But although Eddington himself proclaimed the expedition a success, the results failed to convince the wider scientific community.

Deflected light from more stars needed to be recorded to officially declare Einstein’s theory correct.

An eclipse was due on 21 September 1922 that would begin in Somalia and pass over Christmas Island, before being visible from the Australian mainland in the skies above Wallal.

At first Christmas Island was thought to be the best location, however the weather there was too unpredictable. Wallal, however, averaged two days of rain each September – providing much better odds for a clear sky the day of the eclipse.

But while Wallal’s weather was ideal, the remote location produced a different set of challenges.

Situated behind a row of sand dunes on Eighty Mile Beach, 300km south from Broome, the only infrastructure there was an old telegraph station and there were no roads in or out.

How could all the people and all the large, heavy equipment needed to pull this off be able to get to Wallal? And how could a sustainable camp be built there? The option was immediately dismissed by most of the world’s scientists.

“The British said Wallal was a completely hopeless place and there was no possibility of having an expedition going to there,” says University of Western Australia (UWA) emeritus professor, David Blair.

But Professor Alexander Ross, the then head of mathematics and physics at UWA was determined to convince the international community of astronomers that he could make it work.

“Alexander Ross sussed it all out,” says David, explaining that although the tides at Eighty Mile Beach were a massive nine metres high, Ross knew it was possible to get a ship in as pearling boats frequented the area.

Ross also found out about a fresh water source used by the local indigenous population, and further investigation revealed that decades earlier the State Government had built a well at Wallal to a serve a stock route through the area.

“So he published a rebuttal and sent it around to the most famous eclipse astronomers in the world, including the director of Canada’s Link Observatory, William Campbell and Clarence Chant, who is now described as ‘the father of Canadian astronomy’.”

Both of them agreed they would come to Australia and join an expedition to Wallal.

With Campbell and Chant on board, soon the idea gained momentum and Ross managed to secure support from the Australian Government.

“The Prime Miniister at the time, Bill Hughes, got very enthusiastic about it. He approved that the Navy would supply personnel to help the expedition, and that the brand new Trans-Australian Railway should be used to bring all the telescopes (first coming from California) from Sydney across to Perth,” says David.

In the end, what was achieved is nothing short of extraordinary.

In early September the thirty-person expedition party landed at Eighty Mile Beach, aided by the Royal Australian Navy.

Among the group were astronomers from America, Canada and India, as well as local teams from UWA and Perth Observatory. Documentary makers and photographers also hitched a ride, as did some of the astronomers’ family members.

“They couldn’t bring a steam ship so they got a steam ship to tow a two-masted sailing boat (The Gwendoline) as close to the coast as they could,” David explains. “Then when the tide went down the boat was stranded on the sand but as the tide went up there were lots of waves.”

Thirty-five tonnes of supplies and equipment had to be moved off the boat, up the beach and over a couple of kilometres of sand dunes.

The group used row boats to transport the equipment from the boat to the mud flats. From there owners of a nearby cattle station provided teams of donkeys, wooden four-wheeled carts, and manpower to help carry the huge load.

But although a massive achievement in itself, getting everyone and everything to Wallal was just phase one of the expedition.

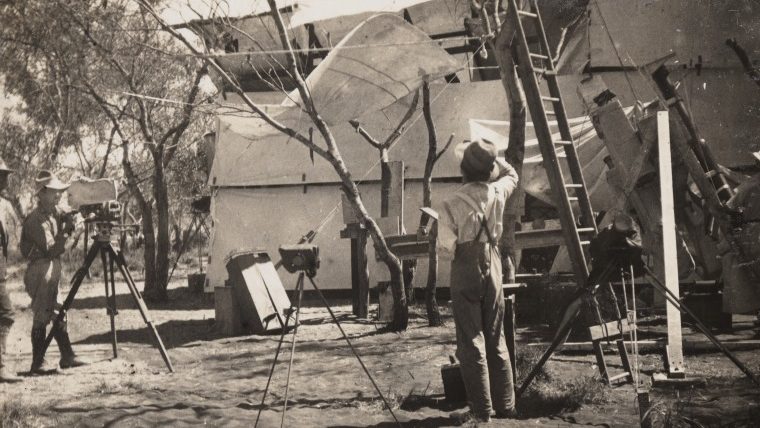

After setting up camp, the equipment needed to be assembled on site, having been transported in pieces

Huge cameras and telescopes needed equally huge mounts to hold them in place – requiring towers so big they needed their own concrete foundations.

But soon these massive structures were complete, wireless communications were established, photographic darkrooms were built, and all the tools and instruments required to capture the evidence they needed had been set-up, tested, finessed, and ready for the eclipse.

How was Einstein’s Theory of Relativity proved?

The photographs taken at Wallal during the total eclipse showed the deflection of starlight.

David explains, “If space is curved then the concept of a straight line is different – straight is curved.”

In simple terms, light always travels in a straight line but if space is curved around the Sun (due to the Sun’s gravitational pull) then light emitting from stars will also curve.

In total, the Wallal Expedition observed 140 stars during the eclipse, and the measured deflection of these stars was extremely precise, with an error bar of less than one percent.

“Their results were so spot on they sent a telegram to the Astronomer Royal saying ‘Prediction sustained: no more eclipse expeditions needed!’,” David says.

And so, Einstein was right. The Walall Expedition had successfully gathered solid evidence of his then-controversial Theory of Relativity.

Indigenous people’s contribution

Walall wasn’t totally uninhabited. At the time 100 Nyangumarta people were living in the area.

In fact, ‘Wallal’ means ‘sweet water’ in the local language.

“In the scientific records there’s hardly any mention of these people,” says David.

“But if you look at the photos what you see is Aboriginal people in almost every photo, especially doing the huge unloading work.”

Other photographs show Indigenous people helping to erect structures, sourcing and carrying rocks for foundations, starting camp fires, and helping around the camp.

The photographs prove their contribution.

While many of the Indigenous people photographed were living at Walall, many more who joined the expedition were workers from the nearby cattle station.

A photographer at the camp also took a series of portraits of the Nyangumarta people in which you see them socialising, and children showing interest in the equipment.

“You also see them peering through the telescopes and things like that,” says David.

“In these photos they look bright and enthusiastic and happy to be there.”

Significance to science

Once Einstein’s Theory of Relativity was accepted as fact, everything scientists thought they knew about space was turned on its head.

Space was curved. It was four-dimensional. It was a deformable medium.

This paved the way for future discoveries like black holes, neutron stars, and most recently, gravitational waves.

“Gravitational waves are ripples in the curvature of space. So, once you have the fact that space can curve, it seems not at all surprising that if it can curve, then it can ripple,” says David.

“We couldn’t have even talked about gravitational waves if we still had the idea that space was rigid.”

The University of Western Australia is hosting a two-week celebration, marking the centenary of the Wallal Expedition with a series of activities and events.

Uncovering Einstein’s New Universe, a book written by David Blair, Ron Burman and Paul Davies, will also be launched during the centenary celebrations.