Computing gives us tools to preserve disappearing languages

IN 100 YEARS, many of the world’s 7000 languages could be extinct. Hundreds of years of oral storytelling will disappear in the space of a couple of generations.

The knowledge and beauty locked up in these languages is irreplaceable. It goes beyond useful dot points about seasons and cultivation and local medicines to untranslatable words and to an entire cosmology. Every language is a multi-generational creative act.

But the sounds, words and stories of all these languages are being captured online, for example on community websites and on YouTube.

Cyberlinguists of the future will have to devise algorithms to decipher the recordings that were made before this mass extinction event.

My collaborators and I want to determine what language data must be uploaded to ensure that the world’s unwritten linguistic heritage is preserved and made intelligible to all future generations.

Capturing languages

Back in 2012 and 2013, we visited Papua New Guinea and Brazil to teach people to use our Aikuma mobile phone software to record and interpret their languages.

Aikuma acts like a voice recorder, but it adds the ability to save and share phrase-by-phrase commentaries and translations. Others experience the original recording with the interpretation.

A French research team has recently taken Aikuma to Africa and recorded about a million words of speech in three local languages.

Clearly, we can readily amass a large quantity of raw language data. But how can we analyse it all?

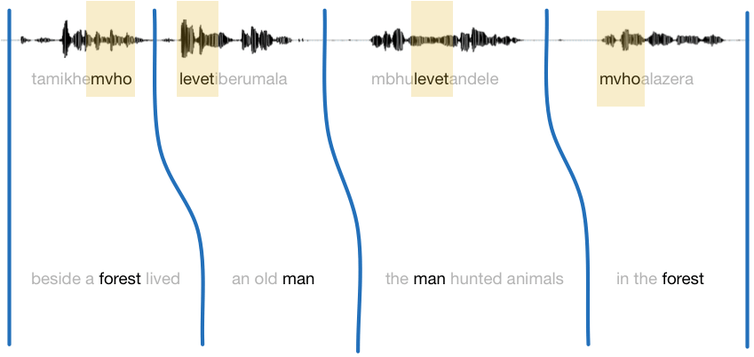

We take a clue from the Rosetta Stone: the keys for decipherment are parallel texts or – in the case of unwritten languages – bilingual aligned audio recordings.

Bilingual aligned audio: acoustic features are extracted from the source audio, and the spoken translation is transcribed using automatic speech recognition, then the two are correlated. (Image Credit: author provided)

Deep learning

Our approach was made possible thanks to a recent advance in the processing of digital images. The method uses artificial neural networks and is known as deep learning.

Show a child an image and ask her to point to the dog, and she does it in a split second. Algorithms can do this too; it’s what enables us to search the web for images.

For the child – and the algorithms – to identify the dog, they must first work out where to direct attention within the image.

Can we do the same for audio? Can we take individual words of the English transcription and correlate them with short stretches of audio in the source language?

Our initial experiments are showing promise, and are being presented this week at an international conference in San Diego.

A digital audio Rosetta Stone

The final step is to close the loop. After lining up source language words with English translations, our algorithm reports its confidence.

We need to exploit this information in order to search tens or hundreds of hours of untranslated audio, flag high-value regions, then present these to people for translation. All while there is still time.

It sounds like a gargantuan task. But perhaps we don’t need to go out to the remote corners of the world any more. After all, social media and mobile broadband now reach 50% of the world’s population and are likely to encompass speakers of every language by the end of the decade.

Accordingly, we are extending Aikuma with social media features. If the app could go viral, then speakers of the world’s disappearing languages would use it to record and translate their stories, guided by our algorithms in knowing what to translate next.

A humble app has solved our problem.

Hacking the dominant culture

But there is no technological panacea. Speakers of the world’s disappearing languages are prioritising their survival. And they are adopting the mindset of the speakers of economically powerful languages such as Chinese, Spanish or English. Small languages are not relevant.

To preserve languages, then, we must go beyond our technical innovation to hack the dominant culture. This is the mission of the Aikuma Project.

Thanks to the growing urbanisation of the world’s population, the speakers of the world’s disappearing languages are often found in cities.

For example, in Australia, Darwin has the greatest diversity of indigenous languages. And thanks to immigrants and refugees, Darwin is Australia’s most linguistically diverse city by population. Darwin will be a laboratory for experiments on the evolution of language.

Live storytelling in indigenous and immigrant languages, Oakland, California, February 2016. (Photo credit: author provided)We will begin with Treasure Language Storytelling at the Darwin Fringe Festival next month: storytelling performances in indigenous and immigrant languages, building on our recent events in the San Francisco East Bay.

Each story will be recorded and shared using the Aikuma app, generating public recognition and evoking pride for each storyteller and for each language. And each bilingual story-listener in the audience will, we hope, be motivated to use the app to record and interpret their parents’ stories for their children.

In this way, we return to the most ancient mode of social interaction, storytelling around the fire. But this time, it is captured on mobile devices, and our algorithms help prioritise the translation effort.

And just possibly, the world’s treasure languages will be sustained for at least another generation, while linguists construct a digital audio Rosetta Stone to preserve the world’s languages forever.

![]()

Steven Bird is an Associate Professor in Computer Science at the University of Melbourne.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

READ MORE:

- Mapping Indigenous languages across Australia

- Aussie slang: why we shorten words

- The largest language spoken exclusively in Australia

- TV helps Aboriginal language revivial