How ‘slanguage’ helped form a new national identity

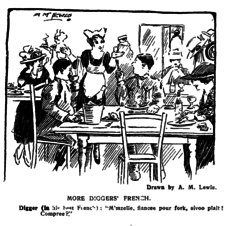

THEY CALLED IT ‘slanguage’. A unique language developed by soldiers on the front during World War One. It was a creative fusion of Australian slang, blue words and bits of French and other foreign phrases.

Classic pieces of Australiana, such as “digger” and “dugout”, were coined in the trenches. Slanguage even gave us the term “Aussie” – a word originally seen by some as downmarket and lower-class.

This collection of new terms and phrases described the new realities of modern warfare, and it became a fleeting publishing phenomenon. When one of the most famous Australian troop publications was created in 1918, it was called Aussie.

Aussie was highly successful, at home as well as abroad. Ten thousand copies of the first edition were produced; there were 100,000 copies by the third and the whole 13 issues were republished in a bound edition in 1920. Aussie magazine, slanguage and other mementos of trench life are showcased in a recently opened University of Melbourne exhibition.

Aussie magazine, issue 12. CLICK TO ENLARGE. (Source: Author provided)

“Compree”, (from the French compris) meant “I understand” or “Do you understand?” “Merci bokoo”, obviously, meant thank you (from merci beaucoup). “Finee” meant done, finished (fini) and if you wanted something done right away, it’d be “toot suite” or “on the toot” (tout de suite).

Resorting to explicit language in print was of course inconceivable, so commentators on trench life wrote around it in Aussie:

Bert stopped laughing when Bill had used his extensive vocabulary sufficiently.

The editor of Aussie, Phillip Harris, argued in his first editorial:

Others don’t like our slanguage. But Aussie would remind these friendly critics that there is a lot of slang in the talk of our Army. And whatever defects our Aussie vernacular may have, it certainly has the virtue of being expressive. Aussie merely aims at being a dinkum Aussie […] And, after all, the slang to-day is the language of to-morrow.

“Dinkum” was not a preferred term of those friendly critics either, nor was “bonzer” or even “digger”. These slang words were associated with a lack of education and an embarrassment to the reputation of Australia, particularly in relation to the home country of many, Great Britain.

Here’s AUSSIE. He comes on strength of the A.I.F. […] His one object in life is to be bright and cheerful and interesting — to reflect that happy spirit and good humour so strongly evident throughout the Aussie Army. […] And that can only be given by you [the soldiers] in your own language and your own way. […] In short, make him a dinkum Aussie.

[…] Aussie does not consider that it shows lack of education for a Digger to call a gentleman a Digger—and the Digger who objects to being called a Digger doesn’t deserve the compliment. […]

Bright, cheerful and interesting stories were the primary focus of this magazine created in France, in the field, under the patronage of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF).

For Harris, the Spirit of the AIF was to be found among the soldiery, not in the higher sphere of commandment. To capture that spirit, to get the tone “right”, Harris saw the vernacular as it was spoken in the trenches as central to conveying in print the otherwise predominantly oral culture of them.

Aussie magazine, issue 5. CLICK TO ENLARGE.

Indeed, the slanguage of Australian soldiers was quite colourful to say the least, and soldiers took great pride in it.

Swearing was clearly a show of masculinity in this male-dominated environment and strong expletives were well suited to its harsh reality.

Long stretches of expletives were particularly welcome in extreme situations involving fear, anger, frustration, an unwillingness to cooperate and other strong negative emotions. They resulted in a form of reappropriation through the language of a situation that otherwise completely escaped them:

He [a grumpy Australian soldier with a temper to match that of the weather: cold, wet, miserable] vomited three mouthfuls of the great Australian slanguage over the figure on the road [that blocked his way back home with his cart] […] He emptied another collection of variegated slanguage over her, [..] He asked the atmosphere emphatically what the unprintable language it thought of the woman [which turned out to be a statue] […]For the first time on record his remarkable accumulation of high-power language had lost its impelling power!

An interesting counter-example may be found in a piece entitled: “Why we should have an instructor in politeness in Corps staff”. In this comic story, a caricature of “soft”, elaborated language is used amidst the harsh reality of the trenches.

There is also a clear comment on social class and on the old-fashioned values of the “old” world that the British Empire represents: dinkum Aussies have dinkum names and don’t talk that talk:

[…]First Digger: Cuthbert, I have reason to believe that the foe has succeeded in striking my shoulder with a projectile. May I beg of you to bind up the wound?

Second Digger: Dear! dear!—how unfortunate! It is almost enough to make one say a wicked word. I shall gladly bind up your wound, Clarence. […]

Of course it would be misleading to solely equate Aussie magazine with its preoccupation with foul language. In fact, detractors of the magazine were primarily bothered with words like “Aussie”.

Harris, who was not a linguist, responded in his second editorial with an incredibly modern statement, that foreshadowed the sociolinguistics (study of language in its social context of production) of the 1960s:

[…] Some say that Aussie is not a nice word. But Aussie is the name that has been practically universally adopted by the Australian soldier for himself. “Aussie” means “Australian soldier” and “Australia”. It’s short and friendly-like. One seldom hears the word Australia or Australian used over here in our general conversation. Therefore, it is not for Aussie to judge whether it is a good word or a bad one – whether it is a soul-stirring euphony or a lingual catastrophe. It is used by his cobbers and that’s good enough for Aussie.

If the impact of Aussie as a title is somewhat lost on 21st century Australian readers, it is clear that back then its claim for one’s own distinct identity from other colonial troops and dominions would not have gone unnoticed.

It was 1918, and Australia was slowly coming to terms with its identity, distinct from its British counterparts. Slanguage – celebrated by Aussie magazine – was a powerful tool to shape and claim a new collective identity. Irreverence, self-deprecating humour and (s)language worked hand in hand to sustain that fiercely independent and proud Aussie spirit.

Somewhere in France – Australians on the Western Front is a free exhibition held at the University of Melbourne, Baillieu Library, level 1, Noel Shaw Gallery until 27 June.

![]() Diane de Saint Léger is a lecturer in Languages and Linguistics at the University of Melbourne. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Diane de Saint Léger is a lecturer in Languages and Linguistics at the University of Melbourne. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

READ MORE: