Gallery: First mountaineers of Mt Everest summit 60 years ago

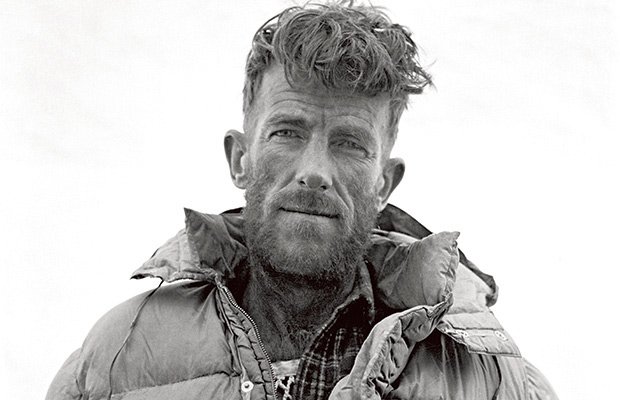

Ed Hillary.

Alfred Gregory (1913 – 2010), photographer on the 1953 Everest expedition, met Edmund Hillary for the first time in 1952, when both were members of an expedition to Cho Oyu in Nepal. Their experience on this climb led to their selection for the 1953 Everest expedition. Alfred later settled in Victoria, Australia.

(The following captions are edited from the book Alfred Gregory – Photographs from Everest to Africa by Alfred Gregory.)

Himalayan foothills.

“The expedition took about 400 porters to carry loads across the foothills, each load about 30kg. They started at Bhadgaon (Bhaktapur), where we had a dump of stores and which lies just outside Kathmandu. These lowland porters usually travelled barefoot or wore lightweight rubber plimsolls (sandshoes) on the month-long walk up to Thyangboche Monastery. That’s as far as they would go; they would be paid and then go back to Kathmandu. From here onwards we used Sherpas to carry our stores to Base Camp, and only a select number of experienced men – about 20, I think – stayed with us and worked with us as high-altitude Sherpas on the climb.”

Mess tent.

(From left) George Band, Ed Hillary, Charles Evans and Mike Ward resting in the mess tent at Base Camp. “For some reason we carried a little Indian Army rum – we just kept it for emergencies I suppose, although I can’t think what emergency that would have been – and this day we had taken a tot or two each.”

The Western Cwm.

“Wilf Noyce is leading porters to Advance Base

Camp. Climbing equipment, together with oxygen bottles and food, made up more than 3 tons of stores that we had to take up there. Each morning we had to make a new track through the fresh, soft snow. It was wearying work, and the heat and glare were intense.”

Hillary and Tenzing.

“Ed Hillary is leading the rope with

Tenzing behind him. They are following three of us up to the highest camp on the mountain at 8500 m. It’s 28 May; the summit support party of George Lowe, Ang Nima and me had stopped to rest, and so I photographed Hillary and Tenzing as they came up to join us. On this day, we were all carrying very heavy loads, the heaviest I think that have ever been carried on the mountain at that height. There was no other way of doing it. We had only one Sherpa capable of helping us, Ang Nima, a great fellow. And so the five of us had to carry all the stores up to this high camp. We were all using oxygen. Oxygen bottles at that time were not as good as they are now. In fact, oxygen had never been used like this on a high mountain. The support party led the route on 28 May, cutting steps where necessary. This allowed Hillary and Tenzing an easier climb, since after that night’s camp they were going to the top. It has often been asked, why didn’t we then go to the top the next day? First, there wouldn’t have been enough oxygen for all of us. Secondly, we didn’t have another tent. In those days the whole idea was to get somebody on top. It was a team effort and we did just that! So the three of us dropped back to the South Col, leaving Hillary and Tenzing to their lonely vigil.”

Base Camp.

“Pasang Phutar Sherpa is putting on his crampons, preparing for a day’s work carrying loads 600m up the Khumbu Icefall. The Sherpas had probably never used crampons before our expedition, but they adapted to them magnificently. They also wore snow goggles to protect their eyes. Snow blindness was a real hazard as the sun was so very bright and there was a great deal of reflected light, even under cloudy conditions.”

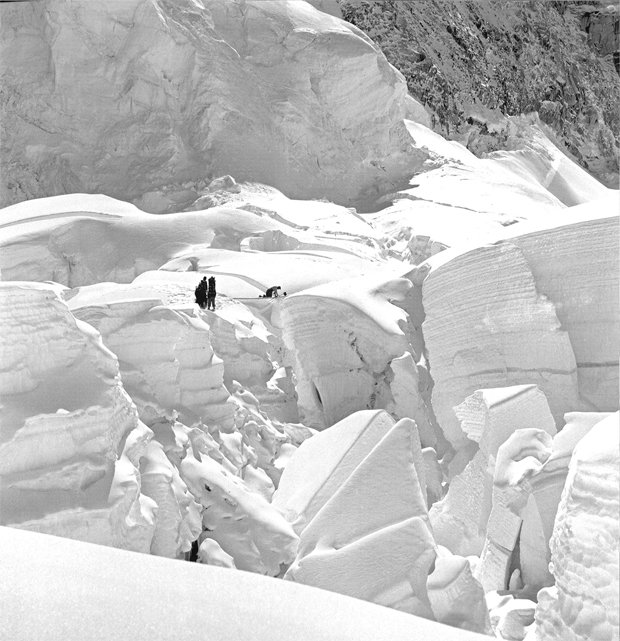

Khumbu Glacier.

Just below Base Camp was this dramatic giant ice serac, which dwarfed the porters moving up along the glacier. Today it looks very different, as global warming and the resultant recession of the glacier have changed the landscape beyond all recognition.

Nawang Gombu.

“Crawling across the ladder is Nawang Gombu with one of my cameras, the Kodak Retina II, around his neck. Nawang is Tenzing’s nephew and was the youngest Sherpa with us. At the time he was a novice monk in Tibet, at the famous Rongbuk Monastery, but when he heard of our expedition, he decided to run away and join us. He was the first man to climb Everest twice.”

Everest’s South Summit 1953.

“I tried to photograph the silence of Everest. The South Col was a pristine wilderness with no footprints on it at all. Just the South Summit lost in the high cloud . . . This is how I like to remember it – before the commercialisation of the mountain, before the advent of hordes and their litter.”

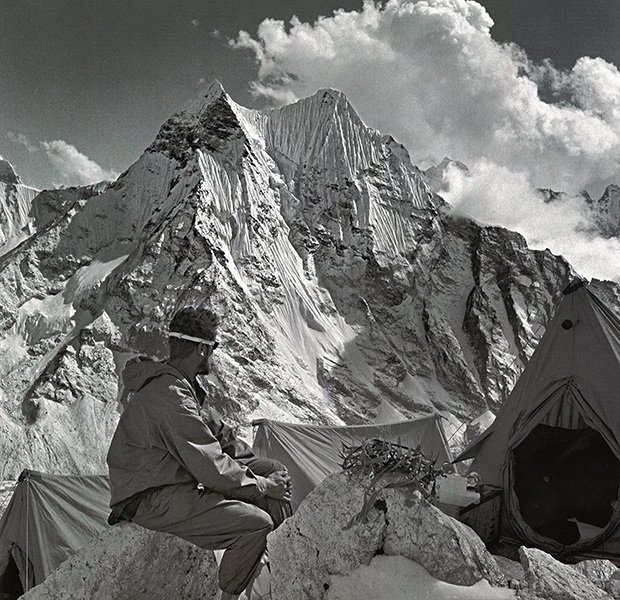

George Band.

“George is cutting steps in the Khumbu Icefall. Whenever Sherpa porters moved through the Icefall to the Western Cwm, a member of the climbing team escorted them up and back down again.”

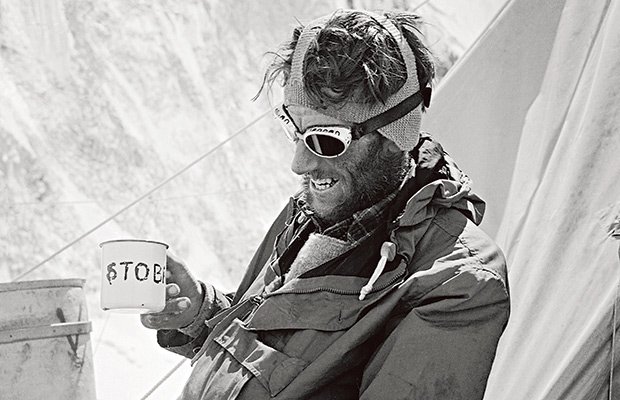

Tom Stobart.

“Tom was the cine-photographer on the expedition. He shot 16 mm movie footage on Kodachrome. He and I worked together a great deal during the expedition. On this day we’d been out in the Western Cwm, where Tom had been shooting some of his fantastic upward pans to the summit of the mountain. We both came back exhausted.”

Taking stock.

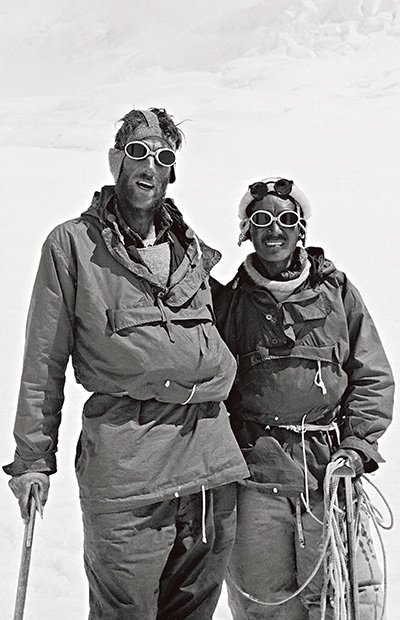

Edmund Hillary, left, and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay rest on Everest’s south-east ridge. The following day, 29 May 1953, the pair made the first successful ascent.

Alfred Gregory (in an interview with Australian Geographic in 2007):

“It was fate that put a camera in my hand and turned me into the official stills photographer for the adventure. I had no idea then that it would be such a historic event, but I was aware that this was photography on an awesome scale.”

Team members, Everest 1953.

Standing behind our hardworking team of Sherpas are, from left, Tom Stobart, Dawa Tenzing, Charles Evans, Charles Wylie, Ed Hillary, John Hunt, Tenzing Norgay, George Lowe, Mike Ward, Tom Bourdillon, George Band, Lewis Pugh, Alfred Gregory and Wilf Noyce.

Hillary.

“He is just back from the summit and drinking a cup of tea using Tom Stobart’s mug. Before we left England our names were painted on our mugs, but since no Sherpa could read English, we never used our own anyway.”

Rope Ladder.

A porter on his way to Camp 3, on the 1953 Everest expedition.

Hillary and Tenzing.

“The two men have just returned from the summit. It was a very exhilarating and exciting moment when they walked into camp. John Hunt rushed out to greet them with tears in his eyes and hugged them both. We’d done it! It was a British team that had at last climbed the highest mountain in the world. We’d climbed Everest! In those days only one expedition at a time was allowed on Everest. Our British team had been given permission for 1953, and if we had failed, the French would have used their permit for 1954.”

Charles Evans, John Hunt’s deputy leader on the ’53 expedition.

“I first met Charles in the Swiss Alps when we were both climbing on Dent Blanche (4357 metres) by a rather difficult route. In 1955 he led the expedition that made the first ascent of Kanchenjunga, the world’s third-highest mountain. He was a neurosurgeon.”

Entrance to the Western Cwm.

“We’d just climbed through 600m of the dangerous Icefall and here was this huge crevass to cross. We had brought with us a light alloy sectional ladder that could be bolted together to form a bridge. Here, Wild Noyce is crawling across it. He is leading a group od Sherpa porters who are ferrying loads up to Advance Base Camp.”

Charles Wylie, Island Peak.

“During the acclimatisation period before the assault on Everest itself, Chales Evans, Chales Wylie, Tenzing Norgay and I made the first ascent of Isalnd Peak. We gave it this name because it stands relatively alone in the Chhukung Valley, between Lhost and Imja glaciers.”

Crevasse in the Western Cwm.

“The lonely beauty of the Cwm is broken by the jagged edge of this huge crevasse. We crossed this one using a snow bridge under the ice wall of Nuptse.”

Home Topics History & Culture Gallery: First mountaineers of Mt Everest summit 60 years ago