Building history: The Endeavour replica

BEYOND A FUZZY NOTION that he discovered Australia, regrettably few Australians are familiar with the extraordinary deeds of Captain James Cook. I wasn’t, until recently, and even former schoolteacher John Longley was hazy on the details until mid-1987, when he read a book on Pacific exploration and learnt something of Cook’s outstanding ability. “I couldn’t believe it,” he told me. “Why didn’t I know this amazing story?”

He knows it by rote now. Three months after John discovered Cook, Perth businessman Alan Bond asked him to oversee the building of the Endeavour replica. These days he’s chief executive officer of the HM Bark Endeavour Foundation, which finances and manages the replica, but even back in 1987 he knew how to build boats. He’d overseen the construction of five for Bond — including America’s Cup winner Australia 11 — but the Endeavour was in a different league altogether.

The concept of building a museum-quality replica of HM Bark Endeavour occurred to trustees of the Australian National Maritime Museum in 1987, in the build up to the Bicentenary celebrations. Bond Corporation offered sponsorship,and work began at Fremantle in January 1988. Two years later, Bond withdrew from the project for financial reasons. Yoshiya Corporation of Japan filled the breach for six months, but then it too withdrew. The half-completed hull of the Endeavour lay untouched for eight months, until a group of dedicated people formed the Endeavour Foundation and raised enough funds for work to recommence. The hull, finished after nearly six years of setbacks, slid down the slipway and into Fremantle’s Fishing Boat Harbour in December 1993.

“WE WERE LUCKY — there aren’t many 18th century ships as well documented as Endeavour,” John said. The ship was launched in 1764 as the collier Earl of Pembroke, but after nearly four years of plying the east coast of England it was bought by the Royal Navy for Cook’s first expedition. Its transformation into a vessel of exploration inclu

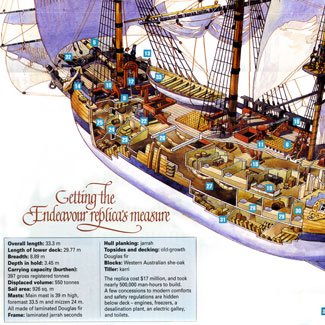

Take a tour of the Endeavour View large image

ded conversion of its cavernous coal-holds into space for nearly 100 men, assorted livestock and two years’ provisions. Drawings made of the ship during its refit became the key documents for the replica’s construction.

An even bigger challenge was finding wood from which to build the 550-tonne vessel. It’s a sign of our times that the great timbers used in the original Endeavour are no longer readily available. The only freshly cut timbers used on the replica were the hull planking, specially cut from the jarrah forests of south-west Western Australia, and the ship’s topsides, decking and masts, made from 400-500-year-old Douglas fir originally earmarked for the construction of US Navy minesweepers.

Luck, generosity and determination provided the rest of the wood. Huge jarrah beams were salvaged from the demolition of a 70-year-old bridge in WA’ S Hotham Valley and a disused Army munitions factory in the State’s south-west. Tuart, a protected species, found its way into the ship after storms blew bushland trees over and a school extension usurped an old playground giant. People would sometimes ring up to offer a prime piece of timber they’d been hoarding under a shed for years.

“I used to joke that our natural enemy was the feral furniture maker,” said John. “We had to get our timber before those blokes grabbed it.”

Coincidence helped, too. As when a shipwright’s father-in-law living at Port Macquarie, in NSW, found that 50 great tallow woods were being felled in a realignment of the Pacific Highway. From the stumps he and a mate obligingly cut out the big “hanging knees” that now support the upper deck.

AS THIS VALUABLE SELECTlON of timber trickled into Fremantle, it fell into the hands of artisans who turned it into the Endeavour. From two to 30 people worked on the ship — depending on the project ‘s solvency wielding traditional hand implements alongside screaming power tools. “Otherwise we’d be still building the ship,” said John. Materials were mostly faithful to the original, but improvements were made where possible. Traditional paints were painstakingly created, but only so their colours could be replicated in the modern coatings used on the ship.

The shipwrights’ biggest challenge came when they had to bend the 7.5-cm-thick jarrah hull-timbers around the Endeavour‘s bluff bow and stern. Early trials with green wood broke one plank in six — a failure rate that would have left them short of timber. They were unwittingly saved when the company storing the hull timber got sick of the project’s delays, and shifted the wood from a shed into the open.The planks dried — yet from then on only a few broke while being bent. In drying, the timber had strengthened and become more flexible. Said John: “If we’d just charged in and built it, it wouldn’t be half the ship it is today.”

AND WHAT A SHIP. “The great quote from Cook is that no sea could hurt her,” said John. “When you sail on her,particularly in a storm, you have this wonderful feeling of this tough little nut of a ship that can take just about anything that’s thrown at her.”

In an age when ships are mostly machines, Endeavour reminds us of the supreme skill, knowledge and courage Cook needed to explore the Pacific. Only by understanding that can we appreciate the scale of Cook’s achievements and be reminded that his was one of the greatest endeavours of European exploration.

Source: Australian Geographic Issue 44 (Oct – Dec 1996)