Like ancient hieroglyphs on old temple walls, the names Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon became firmly etched in the public imagination during the Roaring Twenties.

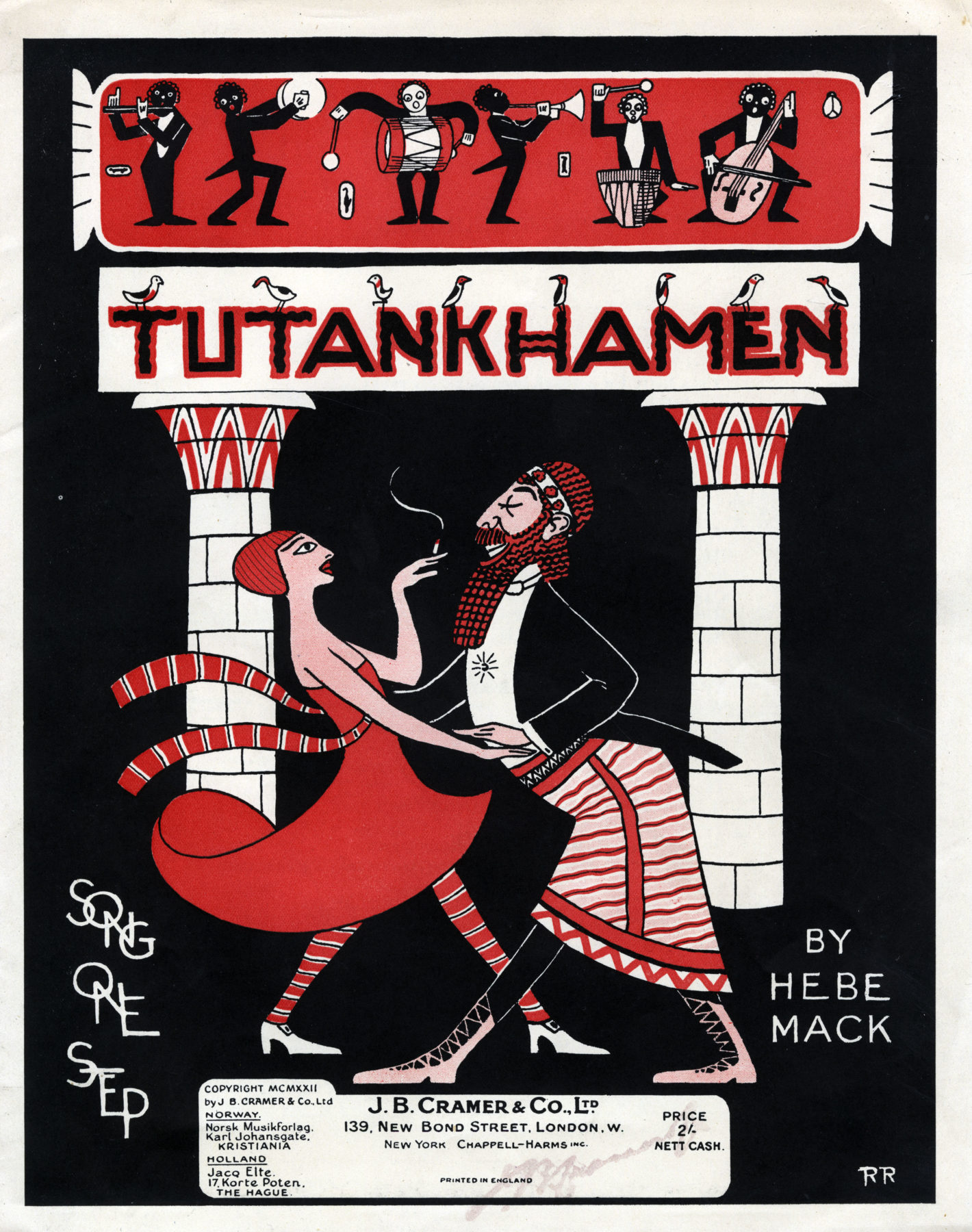

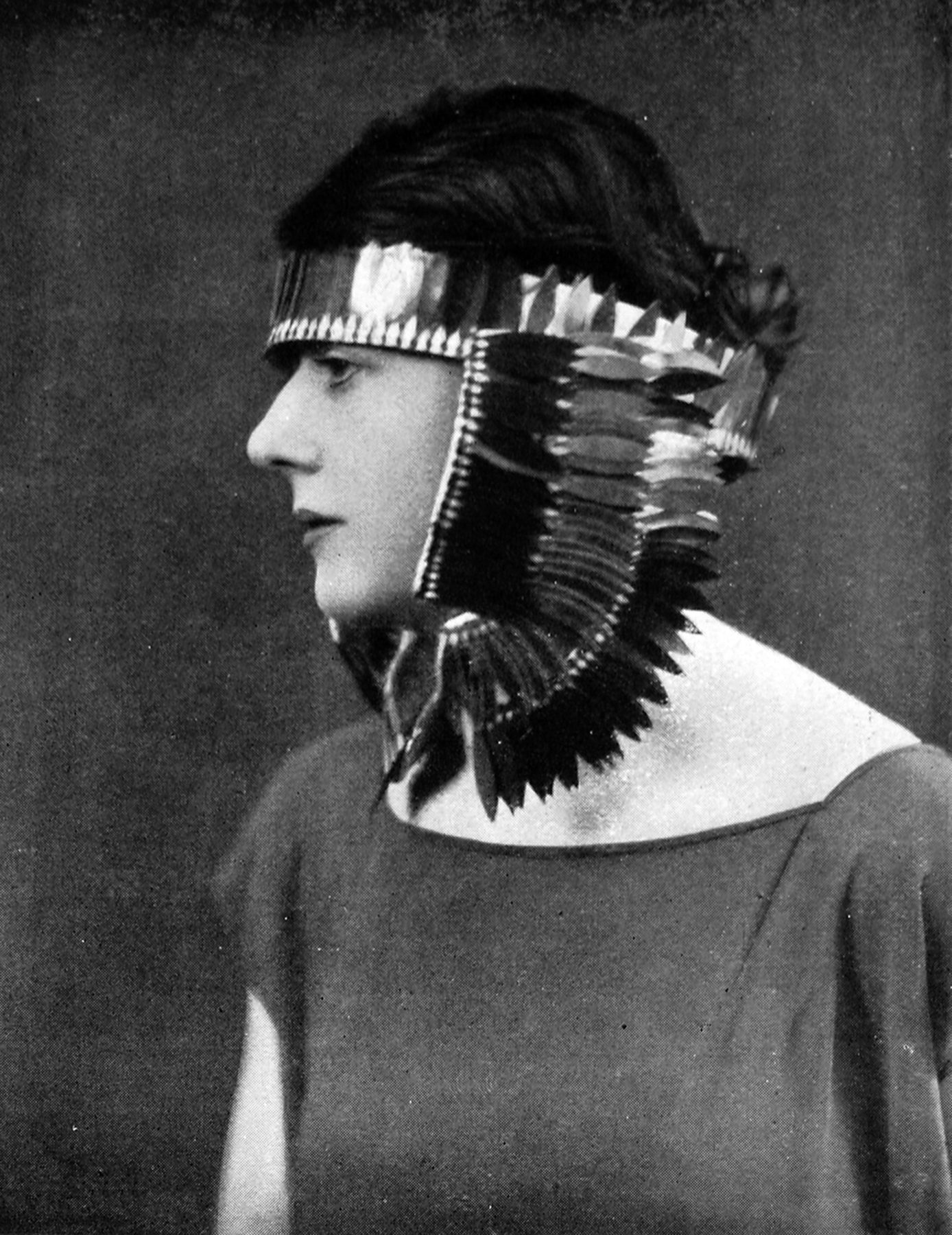

Carter, a British archaeologist funded by the fifth Earl of Carnarvon, discovered the entrance to King Tutankhamun’s tomb on 4 November 1922, unleashing a worldwide sensation that still fascinates a century later. Suddenly Egypt was all the rage, influencing fashion, jewellery, hairstyles and furniture. It inspired songs and dances, and its motifs can still be recognised today in the Art Deco style that came to define the era.

Carnarvon was a keen, wealthy amateur Egyptologist who was underwriting Carter’s work in the Valley of the Kings on the Nile’s west bank across from the old city of Ipet, now called Luxor. Ancient Egyptians believed in an afterlife and were buried with all the necessities they might need there. The valley was a royal burial ground during the New Kingdom (1539–1075 BCE) and provided rich pickings for modern archaeologists and ancient tomb raiders alike.

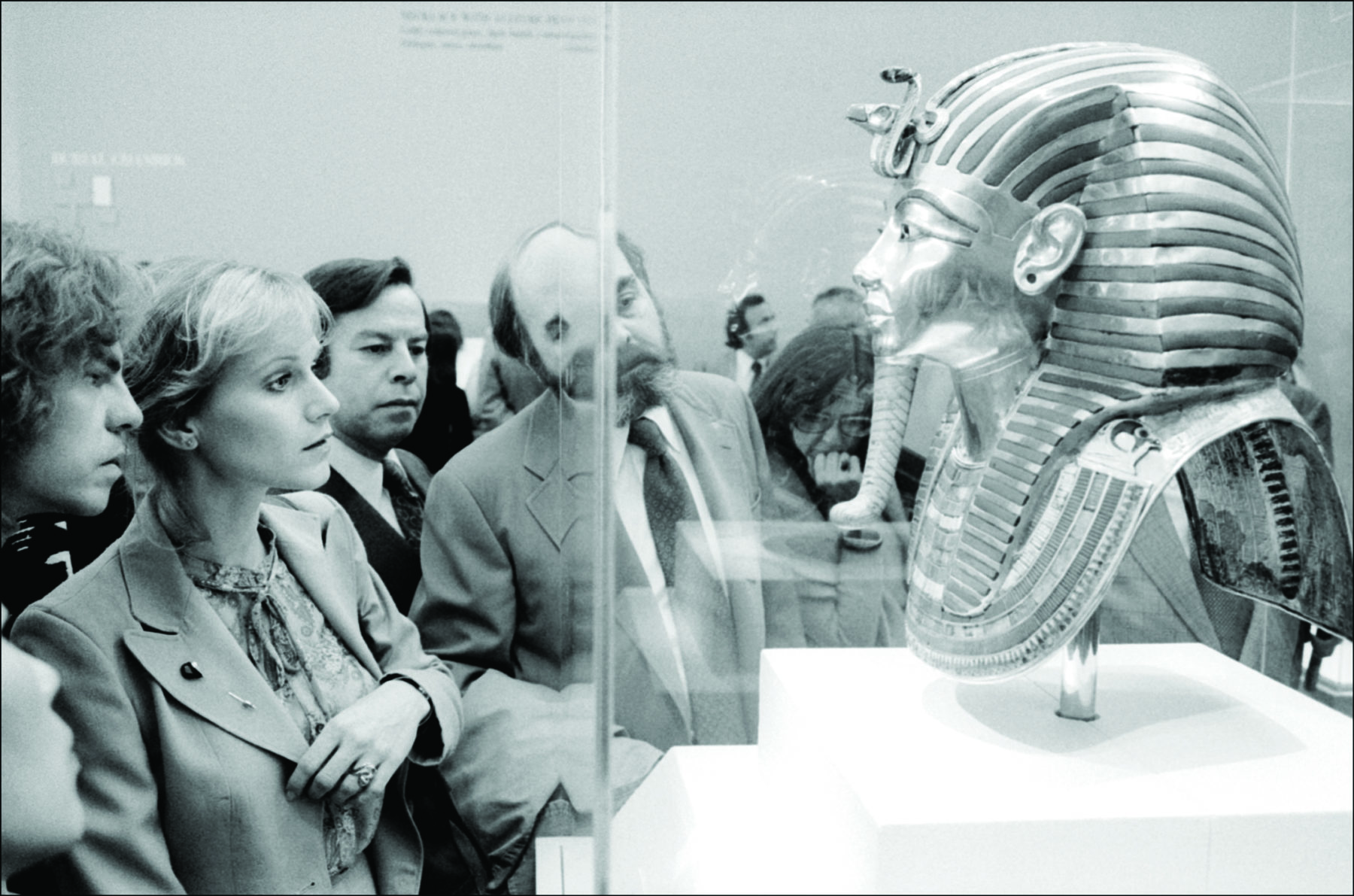

More than 5000 objects would eventually be retrieved from King Tut’s tomb, which had been sealed in 1323 BCE, and, apart from a couple of very early raids, no human had entered the young king’s four small stone burial compartments for 3000 years.

Among the more solid objects, there were fragile items such as linen cloths and even floral wreaths. They ran the risk of disintegrating on exposure to the air or when handled, so an expert hand was called for. That hand belonged to a modest Tasmanian by the name of Arthur C. Mace.

Arthur Cruttenden Mace was working on an American-led dig at Lisht when news of the extraordinary find went public. His reputation was already well established by 1922, and he was seconded to what would come to be regarded as the most important archaeological discovery of all time.

Arthur was born in a Church of England parsonage in Hobart’s Glenorchy on 17 July 1874 to a notable family of Anglican clerics. His grandfather was Charles Bromby, Bishop of Tasmania, and his father a curate. Arthur enjoyed a carefree childhood on a rural sheep property, Woodsden Farm, with his siblings and cousins, but the family relocated to Britain in 1882 upon the retirement of Bishop Bromby.

The family wasn’t well off, but they were well connected. After graduating from Oxford University in 1897 at the age of 23, a career in the church beckoned Arthur. Instead, he opted to work for a distant cousin, the man widely regarded as the father of modern Egyptian archaeology, William Matthew Flinders Petrie.

Arthur’s first Egyptian field dig with his illustrious relative was at Denderah, principal city of the sixth province of Upper Egypt in ancient times and the cult centre of the goddess Hathor, located about 60km north of Luxor. Petrie’s main interest was not in the temple there, but in the old city and its cemetery, which hadn’t yet been excavated. Here, the young apprentice Arthur learnt from the master Petrie the value of painstakingly recording and cataloguing all excavated objects, no matter how seemingly insignificant.

Petrie’s interest in more mundane household objects formed the basis for a dating system using ancient pottery styles and decoration. The austerity of life at Petrie’s dig camps also taught Arthur valuable lessons in self-reliance and resourcefulness, which would make him a valued colleague when doing field work in remote places.

Arthur had a major influence on the innovative way Egyptian objects and art were displayed.

After a few seasons with Petrie, Arthur began working with an American team funded by the Hearst newspaper dynasty and led by the University of California’s George Andrew Reisner. Arthur was appointed lead on a dig at the pyramids at Giza near Cairo; he was becoming a highly skilled and respected archaeologist.

He developed a friendship with fellow team member Albert Morton Lythgoe, which ultimately led to a job offer in the newly established department of Egyptian art at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met), where Lythgoe was the founding curator in 1906. Arthur was sent to Egypt on behalf of the Met to establish a new dig site at Lisht, the cemetery of the Middle Kingdom capital, about 56km southwest of Cairo.

The Met had reached an agreement with the Egyptian government to excavate key sites, with any artefacts to be divided equally between them. Arthur was responsible for the formal applications to the Egyptian Department of Antiquities to excavate at Lisht. He also hired the local workforce and supervised construction of the dig teams’ living quarters.

When Lythgoe arrived later at the site he reported back to the director of the Met: “Mace is carrying everything along and is losing no time in getting things into full swing. He is most enthusiastic over our new expedition, and I consider him, as you know, invaluable to us in the work.”

After his first highly successful season with the Met, Arthur married his cousin Winifred Blyth in November 1907. Winifred was a supportive, practical and cheerful companion to her shy husband during the next few seasons in Egypt. And when, in 1909, Arthur was promoted to assistant curator of Egyptian art at the Met, she took enthusiastically to New York life.

Arthur had a major influence on the innovative ways that Egyptian objects and art were displayed when the Met’s new purpose-built Egyptian Gallery wing opened in 1911. His creative eye and understanding of the need to make objects relevant to the public were ahead of his time; he introduced slide shows and created displays that compared ancient objects with modern life in Egypt.

About this time, Arthur began to be plagued by the health problems that would eventually cause his premature death at the age of 53 in 1928, just six years after Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered. This ensured his name was added to the litany of unexplained deaths among visitors to the site that fuelled the legend of the Curse of Tutankhamun. Lord Carnarvon’s sudden demise started that grim list when he died on 5 April 1923, purportedly from blood poisoning caused by an infected mozzie bite.

Arthur served as a sergeant in World War I. He lied about his age and hoped to serve in Egypt, where his knowledge of language and customs might have been useful. Instead, he ended up training field engineers in Italy.

After the war, Arthur returned to the Met, where he restored two exquisite Lahun jewel caskets from thousands of small fragments that had been discovered by Petrie in 1914. The painstakingly reconstructed cases drew both visitors to the museum and high praise from his peers, and helped cement his reputation as a skilled conservator of fragile objects.

He was back working at Lisht in the autumn of 1922 when Carter’s call for help came.

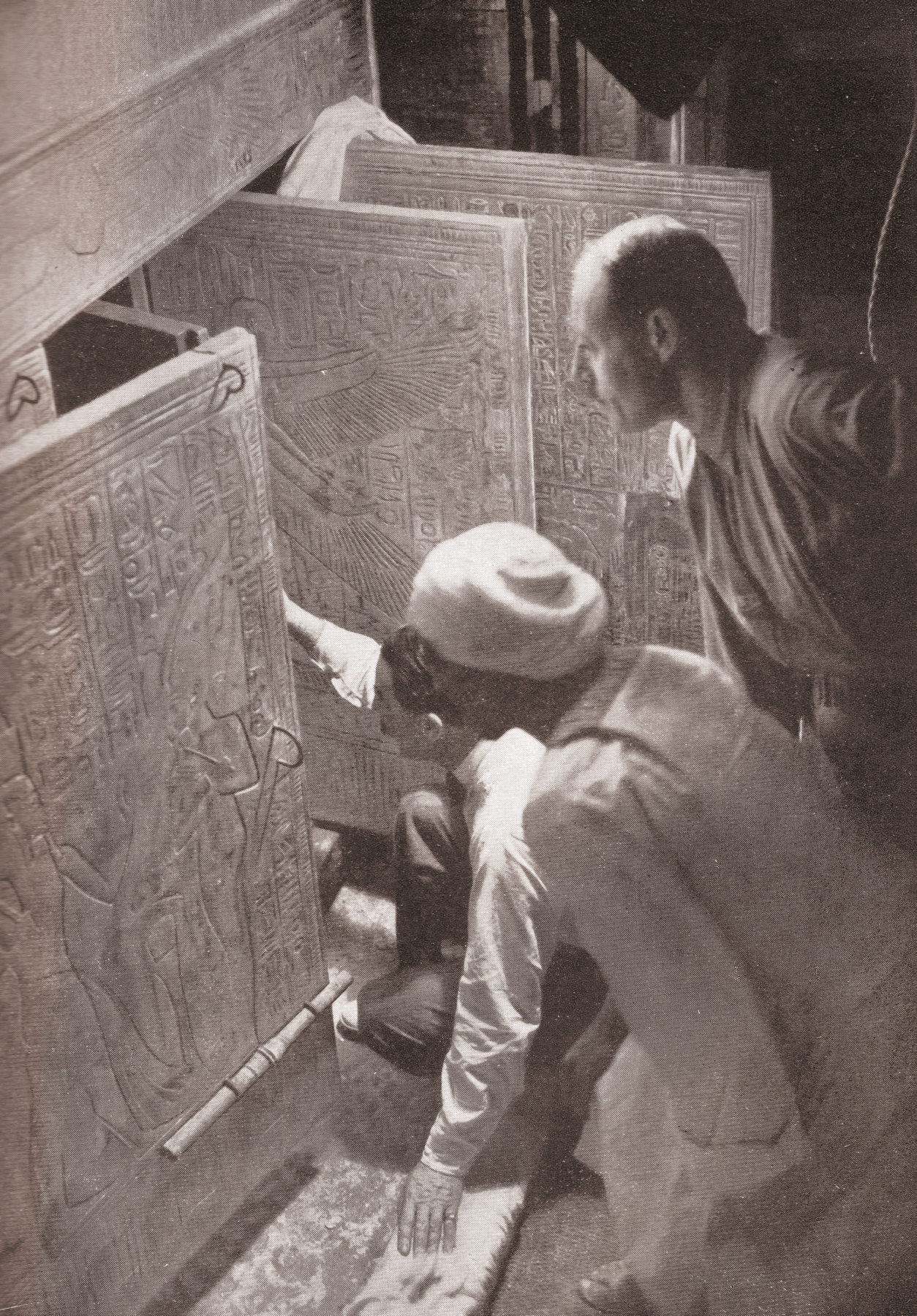

The entrance to the staircase that led to King Tut’s tomb was discovered by one of Carter’s local workers on 4 November. But it wasn’t until Lord Carnarvon arrived from England on 26 November that Carter broke through the sealed entrance below. It was the most intact royal burial site ever found and its significance was immediate.

“At first I could see nothing, the hot air from the tomb causing the candle to flicker,” Carter has been famously quoted as saying. “But presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room emerged slowly from the mist, strange animal statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold.”

“Details of the room emerged slowly from the mist, strange animal statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold.”

Howard Carter

He recognised the significance of the find, describing it as “colossal”, but, as an independent operator unaffiliated with any large academic institution, he needed help – and fast.

Lythgoe sent his congratulations along with an offer of practical assistance and Carter grabbed it with both hands taking on Arthur and Harry Burton, the Met’s talented photographer.

Burton’s first photographs of the undisturbed tomb contents, along with Arthur’s detailed notes before anything was touched or moved, have become invaluable research aids for modern-day Egyptologists.

Carter and Arthur couldn’t have been more different. Arthur was quietly self-assured, but understated and unassuming. Carter was insecure, with a famously short temper, but he enjoyed the limelight. As opposites they got along well, and although Arthur’s work at the tomb site was invaluable, his role has since been largely been forgotten.

Carter estimated that if it hadn’t been for the onsite conservation efforts of Arthur, and that of the British chemist Alfred Lucas, only about 10 per cent of the objects would have been in a suitable condition for exhibition when they arrived in Cairo.

Arthur himself is partly to blame for his lack of recognition, according to Daniela Rosenow, co-curator of Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archives, an exhibition by the Griffith Institute on display at the Weston Library in Oxford until February 2023. The institute is Oxford University’s Egyptology research centre, and holds Arthur’s and Carter’s field journals and private papers.

“In the Tutankhamun story his name doesn’t really come up. But over the one and a half years I’ve been working on this project, I’ve warmed to him, not just because of the documents he produced, but because he seems to be a really decent human being but very much in the background,” Daniela says.

“He was a meticulous person, and he came with everything Carter needed. He had the skill set, the experience, the knowledge and, on a personal level, Carter already knew he could work with him and that their personalities wouldn’t clash.”

It wasn’t just at the tomb that Arthur proved useful. The early 1920s was a period of increasing Egyptian nationalism, and the old colonial arrangements, whereby finds were equally divided, wouldn’t last much longer. Arthur was the more diplomatic negotiator when it came to dealing with Egyptian authorities.

Interest in King Tut’s treasures reached fever pitch and the site was often crammed with dignitaries, the press and tourists, which hampered the work. Carter and Arthur worked fast to produce a book for the eager public. The Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen: Search, Discovery and the Clearance of the Antechamber, published in 1923, was an instant bestseller. It’s been in print since, and while early editions credited both men, many modern editions fail to acknowledge Arthur as co-author.

He worked as a conservator at the Tutankhamun site for two seasons, in 1922–23 and 1923–24, preparing thousands of objects to be displayed at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. His failing health prevented any further field work and in 1928 he passed away. While the role of Arthur Mace in the legend of Tutankhamun

may have faded from view, his contribution to the New York Met hasn’t been forgotten. His finely detailed journals and exhaustive field notes are still referred to by archaeologists working in Egypt today.