On the Port Davey Track, deep inside the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, a team of park rangers is thigh-deep in black mud. Their progress is slow as the mud sucks at gaiters and boots, which have become as heavy as bricks.

Ahead of them, the peaks of the Western Arthurs serrate the sky, and two hikers splash towards them, returning from this most challenging of Tasmanian mountain ranges.

“How’s the mud ahead?” asks James Flittner, a ranger far from his usual beat on the Overland Track. The hikers shrug: “We’re desensitised now.”

This section of the Arthur Plains is one of the most notorious stretches of mud in South West Tasmania. But these rangers have been out, in various configurations, for 19 days on a mission to cross the state. Behind them have been greater challenges than this mud, and even greater ones still lie ahead. They shrug also and walk on. The Tasmanian Ranger Relay continues its journey south.

Rewind almost three weeks to the northern Tasmanian town of Penguin. The boots were lighter, the legs fresher, when I joined five rangers and park staff at the Big Penguin monument near the town’s foreshore. Auntie Erica Maynard welcomed us to Country before we stepped through the morning traffic and set the relay in motion.

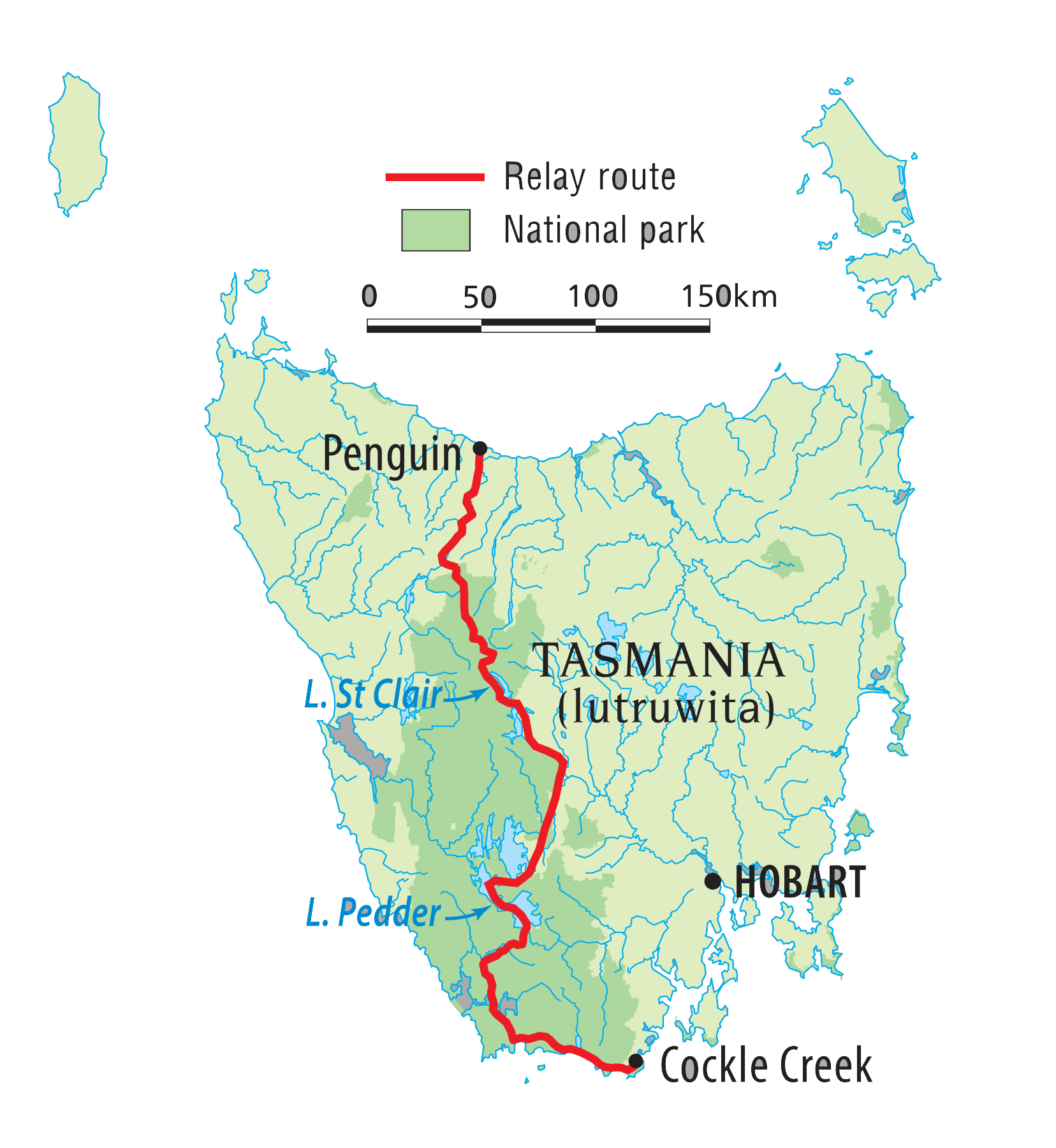

During the next month, the relay would travel 525km by foot, bike and kayak from Penguin, on the edge of Bass Strait, southwards to Cockle Creek near Tasmania’s most southerly tip. Organised by the Tasmanian Rangers Association (TRA), a professional organisation of more than 80 Tasmanian park rangers and staff, the relay’s goal was to raise money to help fellow rangers at Timor- Leste’s first and only national park, Nino Konis Santana National Park.

The project was initiated by Brendan Moodie, chair of the TRA. “I got the idea when I was at the World Ranger Congress in Nepal in 2019; I saw how hard some rangers were doing it around the world,” he explained. “The guys in Timor-Leste have had a really rough time. The total funding for the park last year was about $52,000, including wages. Their government-supplied motorbikes broke down eight or nine years ago, so they’re using their own, which aren’t in much better condition than the original ones. It’s rangers helping rangers.

For the first week, the relay would follow the little-used 80km Penguin Cradle Trail (PCT), which links into the Overland Track. The PCT begins along the low Dial Range, ascending through the creases in its slopes. Tannin-

brown streams filled with recent rains poured down beside the path, fern fronds unspooled like party horns, and, beyond the picket-straight eucalypts, the sky was dark with more rain.

“This is so pretty,” Kate McClafferty murmured at intervals. Kate’s a visitor reception officer at Cradle Mountain and the PCT finishes at the door of her office. “This is the furthest I’ve ever walked to go to work, yes,” she said, laughing. “It’s pretty unique in that regard. This trail was already on my to-do list for this summer, but the relay came up a bit earlier. It’s just remarkable in here. It’s really something special.”

Cutting through the Dial Range is the Leven River, which the team reached late on the first morning, turning upstream on a beautiful stretch of walking along the abandoned Lobster Creek Tramway. The river flowed wide and slow after its tumultuous passage through the Leven Canyon, which forms the toughest stretch of the PCT and is three days ahead for the relay.

It was a section that only three of the team – Kate, Hannah Waterhouse and Darren Emmett – intended to hike. Arthur River ranger Ben Correy and I planned to drop away on the third morning, and Queensland ranger and chair of the Council of Oceania Ranger Associations Jo Nelson would exit to celebrate her first wedding anniversary. But even before the trio could reach the canyon, things would go awry.

As we neared camp at Hardstaff Creek on the first night, Hannah, a ranger in the field office in Ulverstone, on Tassie’s north coast, left her backpack beside a four-wheel-drive track, walking out to a nearby car to grab a tent and food for the coming week. As a burst of hail arrived, the rest of the team sprinted into camp to pitch tents. When Hannah returned, her pack was gone – stolen. Her relay had come to an abrupt and heartbreaking end.

“Why would you steal a pack?” she asked, bewildered. “Packs are disgusting, full of gross clothes and rubbish. It’s quite violating. That was my mini house for a week.”

Over the course of the relay’s 31 days, more than 20 rangers and parks staff would tag in and out of the journey. Some would be with it for a day, others for a week. But there was one person who would cover the entire 525km – Darren Emmett.

He’s been a ranger on Maria Island National Park for almost a decade, and before that, spent eight years as an Overland Track ranger. For this month, Darren would be the single common thread through the relay. “I thought it was a good opportunity to link a few tracks up, and I’ve never done something this long before,” he said. “Trying to do it under your own steam is quite difficult, so I jumped on this. It was nice to get walking, because trying to organise enough food and all the gear took a fair bit of time. It was quite exciting to get going.”

When I left Darren and Kate on the third morning, the weather forecast for their day through the Leven Canyon was abysmal, with about 40mm of rain predicted. The river level rose alarmingly, and as the pair ascended into high alpine terrain beyond, rain continued falling. Kate’s tent would succumb to leaks, forcing her to abandon the relay a day out from Cradle Mountain, leaving Darren to walk on alone. A leg that started with seven people was now down to one.

But Darren would be on his own for just one day, because waiting for him at the Cradle Mountain Visitor Centre to finish what they’d started were Kate and Hannah. In the six days since Hannah had abandoned the walk, the TRA had launched another internal fundraiser, gathering almost $1000 from its members to help replace her stolen gear – rangers helping rangers, yet again. Together, the trio walked the final 5km to the start of the Overland Track at Ronny Creek – a symbolic end to an eventful week that showed no sign of abating.

That afternoon, southern Tasmania went into a three-day COVID lockdown. The relay was still in the north, meaning it could continue, but only three rangers shouldered packs and set out onto Tasmania’s most famous track into the continuing rain.

For much of the way, traversing Tasmania on foot is a simple navigational puzzle. The PCT links into the Overland Track in the north, while the Port Davey Track connects with the South Coast Track in the south. But in the middle, between Lake St Clair and Scotts Peak Dam on Lake Pedder, there is no linear trail. The relay bridged the gap by turning itself into a triathlon that covered the ground by bike, foot and kayak.

On a map it looked like the simplest part of the journey – predominantly following roads to Lake Pedder, which would be crossed in kayaks – but it proved nothing of the sort. “Mentally, I was thinking I could relax, take it a bit easy, but I was way wrong,” Darren later said. “It proved to be much harder than I anticipated.”

On the southern shores of Lake St Clair, I rejoined the relay as it took to mountain bikes, cycling on tracks and unsealed roads that wrapped around Lake King William into Butlers Gorge, where a concrete canal ran side by side with the River Derwent – two waterways flowing in lockstep. Beyond the gorge, the relay hit the modern reality of a highway – even if the Lyell Highway is a highway only in name. Along 10km, only a handful of cars passed the small train of four bikes, before the relay turned away again at Wayatinah. Beyond the tiny hydro town’s edge, the Derwent and Florentine rivers converge. A decade ago, the Florentine valley was a battleground between loggers and protestors.

As the relay descended to the river, it was leaving the big mountains for the big trees. But first the Florentine River had to be crossed. The unsealed road through the Florentine valley used to be a popular shortcut for drivers between the west coast and the south-west, but six years ago the wooden supports for the bridge over the river burnt in a bushfire and the bridge collapsed. The only way across the wide river now was to ford it on foot.

Filled with recent rain, the river was fast and high. We slung our bikes onto our shoulders and waded through the tannin-stained waters that flowed around our hips. A few metres downstream, the old bridge lay crumpled in the river.

For the next 24 hours, the relay would be a ride through the yin and yang of the Florentine valley – lush rainforest along one side of the road, freshly logged coupes on the other. In a single day on the bike, Darren covered as much distance – more than 80km – as in the previous week on foot.

The team made camp this night in a mossy clearing, 5km short of the relay’s halfway point. Suitably, word came through that half the fundraising goal of $25,000 had also been passed that day. The next morning, there was a 20km ride to the Adamsfield Track, and we pedalled through rain. Leeches hitchhiked from camp on our legs, and we arrived mud-splattered at the start of the track, where the relay’s mode of travel reverted to foot.

The Adamsfield Track cuts west from the Florentine valley to the remote and abandoned town of Adamsfield, where the alloy osmiridium had once been mined. It had been home to about 1000 people and was now engulfed by wilderness. I set out on the track with Darren, Shirley Zheng and one of the relay’s organisers, Eric Tierney. The mood was light. This 13km walk felt like a stroll – a midway breather – compared with the longer tracks and road stretches that bracketed it.

I walked with the trio to the remains of Churchill’s Hut, where the last Tasmanian tiger was captured in 1933. This area was razed by fire in 2019 and the hut obliterated. Metal lay about, twisted into grotesque shapes, and glass appeared liquified by the heat. It was as though the hut had melted into the earth. Even the rocks we walked over still appeared scorched.

Just beyond the hut, I turned back, returning to shuttle a vehicle and bikes to Adamsfield, where I would rejoin the relay for the final bike ride to Lake Pedder. I half expected the trio to beat me into Adamsfield, but their way ahead turned into an epic experience.

Even before I left them, it was clear that few people had walked this track since the bushfire. But past its Florentine River crossing it all but disappeared and maps showing its course proved inaccurate. The team inched forward, as good as lost.

“It was meant to be a walk in the park, [but] it wasn’t,” Eric said. “We headed off with two GPS [trackers] on smartphones and a Garmin inReach [satellite communication device], and it turned out that the mapped route…well, they got it wrong. We were briefly contemplating the prospect that we might be out there for the night. But we were able to get messages to Brendan [Moodie], and Brendan was able to send messages back telling us we were on the right path.”

On dusk, six and a half hours after setting out on what was planned to be a three-hour walk, they wandered into Adamsfield.

A precursor to the mud on the Port Davey Track came the next day on the Saw Back Track, a notorious 4WD route that becomes so pooled with mud that the Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service closes it every winter. The Saw Back’s point of difference to the Port Davey Track was that the relay was crossing it on bikes.

Local ranger David Holley was the only member of the team with any prior experience of the track, and hearts sank when he turned up with a fat bike – if he needed tyres wider than a mountain bike, the rest of us were in for a mud fight. “I knew this track was going to destroy my other bike,” he said.

The 12km track rises over the Saw Back Range, a remote line of mountains topped with the sawtooth-like peaks of its name. The climbs were steep, but its greatest challenges were on the range’s shaded southern side, where the pits of mud were so deep our pedals were often under water.

It was Darren who suffered most across the track. Twice, branches stuck in his bike’s rear derailleur, bending the gearing system into the spokes of his wheel. Finally, he could ride the damaged bike no more, pushing it for the last kilometre and borrowing another bike for the final road stretch to Lake Pedder. The baton – in this relay’s case, a gold-painted toilet brush – passed to a new team, with only Darren continuing on his unbroken journey.

For three uneventful days, the relay team kayaked across Lake Pedder, finishing by Scotts Peak Dam within half an hour of the time predicted in the schedule laid out months before. As the next team set off walking on the Port Davey Track, they were beginning what might be Tasmania’s longest stretch of continuous wilderness track – 155km along the Port Davey and South Coast tracks to Cockle Creek. The long march to the finish had begun.

Cut during the 19th century as an escape route for shipwrecked sailors, the Port Davey Track is walked by only about 80 people a year. None of the five relay members had ever tackled it. It’s a track through the mountains rather than over them, threading along valleys to distant Bathurst Harbour and the settlement of Melaleuca.

I joined them for the first day. It was the only blue sky Darren had seen for more than two weeks, yet, even slowed by mud, they moved determinedly because heavy rain was forecast two days ahead, and one of the Port Davey Track’s defining features is the number of creeks it crosses.

In two gruelling days, the party approached Spring River, which is usually reached in four days. Fatigued, they camped just short of their intended stop on the bank of the river. It was a forced but fortuitous decision.

That night the rain arrived and more than 80mm washed over the area. The creek beside their camp broke its banks, and by morning water was pouring through the tents. They moved to higher ground and holed up for a day.

When they set out, the creek was still fairly high and effectively dammed by the volume of water in Spring River, but the five walkers pressed on. Spring River had swollen to become hundreds of metres wide. Wading through water up to their knees and then their waists, the rangers used tape in the trees for navigation.

The team was in the cold river for almost an hour. Somewhere beneath them, completely submerged, was the campsite they’d been intending to reach two nights before.

“It would have been horrendous if we’d camped there,” Darren said. “It definitely would have brought the trip to an end. We would have lost gear for sure, and people would have been hypothermic. We’d have been in a pretty serious predicament.”

The South Coast Track is one of Tasmania’s longest and toughest walks, threading along the wild and muddy south coast and over the infamous Ironbound Range. But it was one of the relay’s few near-incident-free stretches. One member became ill and turned back soon after setting out from Melaleuca. But the sun finally burnt through, the four remaining rangers moved well, and by the time they arrived at Lion Rock – the relay’s final camp, behind one of Australia’s southernmost beaches – the mood was festive.

James’s partner Emily hiked in from Cockle Creek carrying beer, a carrot cake and a feast of sausages. A barbecue celebrated the approaching end.

At dawn, beside the beach’s namesake, Lion Rock, Darren stood looking over the Southern Ocean and stretched out a month of hard work from his body. In 8km, the relay would be over. “I’m looking forward to some creature comforts,” he said. “But it’s gone very quickly. I’ve never once felt like it was getting too much, or I wanted it to finish.”

A few kilometres from the end, they were met by Brendan Moodie, who’d walked in from Cockle Creek to welcome them to the literal end of the road.

“It’s been a great thing to be involved in,” he said. “It’s terrific to see that everyone’s out safe, and we’ve achieved the goal of buying the eight motorbikes. I reckon we might do it again at some point.

“We’ve got some other things to concentrate on now, funding-wise, for the TRA for the next two years, and we’ll see where we go after that.”

North to south

The ranger relay strung together the Penguin Cradle Trail, Overland Track, Port Davey Track and South Coast Track, with backroads and tracks between Lake St Clair and Lake Pedder.

Relay total 525km

-By foot 335km

-By sea kayak 42km

-By mountain bike 148km

-Elevation gain 23,000m

-Raised $22,000

-Eight new motorbikes and associated equipment supplied to Timor-Leste

-27 rangers took part on the ground, but many more assisted with planning

and logistics