Solving a sea monster mystery

So it seems apt that our country’s most infamous sea monster case hails from this rugged, sparsely populated coastline. The ‘mystery’ dates to winter 1960 when two stockmen came across the remains of a giant, slug-like creature on remote Four Mile Beach near windswept Granville Harbour. They estimated the creature to be 20ft long, 18ft wide and weigh 5–10 tons (6m x 5.5m, 5–10t).

Apparently, it also emitted a very strong smell and appeared to be covered in a fine, wool-like coating. These days, such a find would go viral on social media within minutes. But in the 1960s it took 18 months before news of the discovery became public, eventually leading to a global media frenzy.

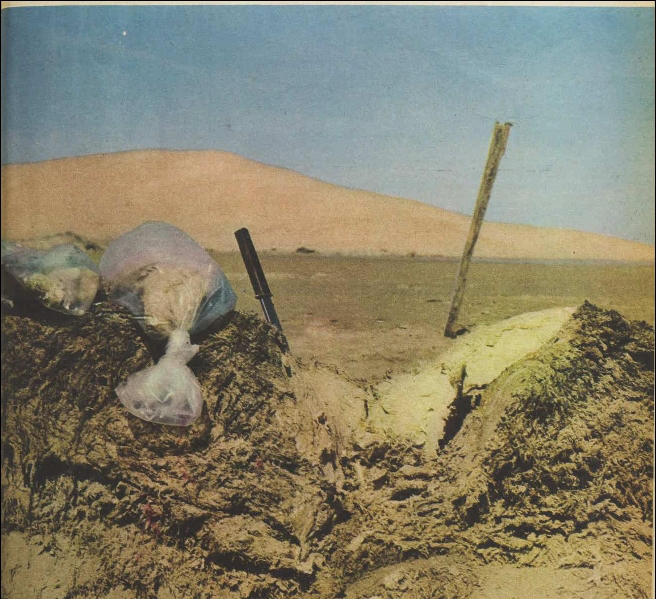

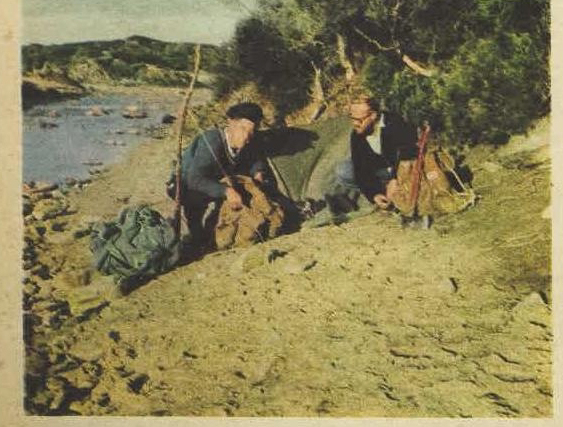

A team from CSIRO, the University of Tasmania and the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) attended the scene. Remarkably, despite the time it had lain decomposing, enough of the creature remained for it to be photographed. Samples were collected and sent for testing. So had a denizen of the deep beached itself? Was it a new species?

Tests indicated something far more mundane – whale blubber, which had likely fallen of a whaling ship. Nevertheless, the prospect of it being a monster remained appealing to many. This wasn’t helped when a chunk of the blob was stuffed into a jar, displayed at TMAG and emotively labelled “west coast monster”. Famed British biologist and cryptozoologist Ivan T. Sanderson even coined the term “globster” to describe it, a term still used for similar blobs that wash up on beaches.

Australian Women’s Weekly in 1962/NLA

Australian Women’s Weekly/NLA

Australian Women’s Weekly/NLA

In 2004, attempting to finally put the monster theory to bed, an international team of scientists undertook further analysis of the “monster” tissue, along with samples from several other globsters found elsewhere in the world.

Writing that year in the University of Chicago’s The Biological Bulletin, they concluded all blobs examined “represent the decomposed remains of great whales of varying species. Once again, to our disappointment, we have not found any evidence that any of the blobs are the remains of gigantic octopods, or sea monsters of unknown species.”

Apart from TMAG’s jar of pickled blubber, other reminders of the Tassie monster include a file stashed in a vault at the National Archives of Australia in Canberra. It details CSIRO’s investigations into the “creature” and includes a fascinating letter from a Swedish correspondent who linked the globster to sea dragons killed by Norse gods Thor and Odin that were carved into Viking ships. Yes, really!

In 1989 the Nomenclature Board of Tasmania named a creek close to where the globster was found Monster Creek, ensuring the location of the world’s first globster is forever remembered.