Escaping the epicentre: my journey from Wuhan to Sydney

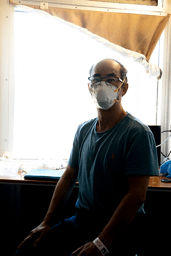

In quarantine at the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centre.

I was born in Wuhan, a large city located in Central China’s Hubei province. I completed my tertiary education at Wuhan University and spent the first twenty years of my life calling Wuhan home. Today, my elderly parents still live in the city with my oldest sister and her partner.

I relocated to Sydney, Australia, in 1990 to pursue doctoral studies at the University of Sydney. When I arrived all those years ago, no one had ever heard of Wuhan. Every time someone asked me where I had come from, I had to refer to the bigger cities like Beijing or Shanghai, or to well-known land features such as the Yangzi River, in order to provide a rough geographical location of Wuhan.

Thirty years have passed and Wuhan has gone on to become China’s seventh most populous city with a population of 11 million. Still, Wuhan is not a widely known city amongst many Australians.

But that all changed in January this year.

Early January 2020: Wuhan Coronavirus Outbreak

On 7 January 2020, my wife and I joined our older daughter in Wuhan. It was a typical winter day, overcast and cold. I was involved in research collaboration with Huazhong University of Science and Technology (HUST) and was scheduled to return home to Sydney on 29 January, after spending Chinese New Year with my parents.

On 12 January, over dinner, my wife and I first heard whispers about a Wuhan virus. A local friend of ours mentioned that there were rumours of an anticipated virus outbreak. Some hospitals were preparing to significantly increase the number of patient beds in the vicinity.

We didn’t pay much attention to this rumour, as everything appeared normal. People went to work, and shops and restaurants were operating as usual. I travelled to HUST every day via the newly built Wuhan Subway network. It was always crowded during the peak hours. No one wore protective facemasks.

On 13 January, the day my daughter was leaving Wuhan to return to Melbourne, I accompanied her to Tianhe International Airport. Nothing was out of the ordinary.

Five days later, when my wife went to Tianhe International Airport to board her flight to Sydney, I saw a few people wearing facemasks. Still, not enough to garner my attention.

But things changed very quickly after that.

The very next day, on 19 January, the Chinese social media platform, WeChat, was buzzing with news about a coronavirus outbreak. Suddenly, it seemed every hospital in Wuhan was overcrowded with patients. I heard that people were dying.

That was when I began to realise the situation was serious. As information started flowing in, the worst was yet to come.

Everyone on the streets began wearing facemasks. In restaurants, staff checked customers’ body temperatures. There was uncertainty as to just how bad the situation actually was.

Friends outside of China began messaging me. From midnight on 22 January to the early hours of the morning, I constantly received messages from my overseas friends telling me that Wuhan would soon be in lock down. They advised me to get out of Wuhan as soon as possible.

I started to seriously consider it.

But then the lockdown came into effect. The situation became completely out of control. Locking down an entire city was the last line of defence for the government to fight the deadly contagion.

Fleeing Wuhan in this state of panic and confusion was out of the question, not only as there was a lack of ground transportation to the airport, but also because my parents needed me in this extremely difficult and sudden situation.

From 23 January, I stayed at home with my parents, sister and her partner. As each day passed, we received more depressing information about Wuhan citizens suffering from the coronavirus outbreak

That’s when the reality of the situation hit me hard; the lockdown would not be lifted anytime soon.

I experienced conflicting emotions about this.

On one hand, I was grateful to be able to look after my parents and do something for them, but I was anxious about what would happen next. My wife and daughters in Australia were extremely worried.

2-3 February 2020: 40 hours fleeing Wuhan

At the end of January, the Australian government announced its Wuhan evacuation plan. After much consideration, I decided to apply for it.

It was a hard and sad decision for me.

My wife and daughters wished me to return as soon as possible. But I really worried for my parents, especially my father who turned 93 this year. Both my parents are quite frail and are dealing with underlying health conditions.

I prayed that my parents would be able to overcome this difficult period. The Wuhan hospitals were stretched beyond their limits in dealing with coronavirus-infected patients. Wuhan citizens with other health and medical conditions had nowhere to go to access available doctors and medical staff. Now, I could only pray my parents did not get sick.

On 1 February, I received the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s (DFAT) confirmation email informing that I had been shortlisted for the Qantas assisted evacuation flight departing at 2:00am on 3 February.

I was asked to arrive at Terminal 3 in Tianhe International Airport before 6:00pm of 2 February.

I had a very simple farewell lunch with my parents and sister. On 2 February, my sister’s partner drove me to the airport. As all public and private transportations had been banned, we had to apply for special permission to drive to the airport.

It was a cold and drizzling afternoon when we drove through the main streets of Wuhan CBD. For the first time in my life, I witnessed Wuhan as an empty and silent city. No one walked on the streets, only a few cars were driving on the road. In less than 30 minutes, we reached the main gate of Tianhe International Airport at 3:20pm. Normally this journey would have taken at least an hour.

The main gate was heavily guarded by traffic control officers and medical staff who all wore full body protection suits. After waiting in the car for more than two hours, I finally arrived at the terminal at 6:00pm.

But the long waiting had just begun.

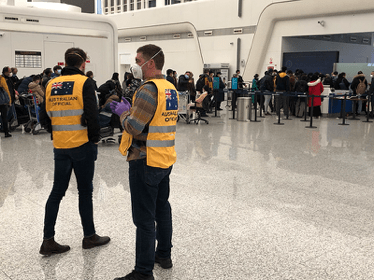

The airport was already full of evacuees – in fact, there were four countries undertaking evacuation operations at the time. We had to wait for more than 5 hours before our boarding passes were collected and our luggage checked in.

Thousands of evacuees stood in the queue, ready to pass the custom security checkpoint, but there was only one airport staff at the entry gate.

At 3:00am the next day, together with over two hundred evacuees, I was still standing in the long queue. Everyone was very exhausted. Children were crying and some senior evacuees slept on the benches.

I finally boarded the plane at 6:10am.

When the plane took off two hours later, I felt relieved. But there was also a heavy weight in my heart. I did not know what would happen to my family left behind in Wuhan.

During the eight hour flight, we received great support from the volunteer Qantas flight attendants who served us drinks, snacks and one main hot meal. It felt just like a normal flight – except everyone wore facemasks. The AUSMAT medical staff paid great attention to each evacuee’s health status.

At 4:30pm local time, the plane landed at Learmonth Airport in Exmouth, Western Australia. The clear, blue sky of a 40-degree day greeted us. Through the speaker, the flight captain said: “We are glad to take you back to Australia. Welcome home.”

That was a very moving moment for me.

We were transferred to the nearby Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Base, where we stayed until 2:00am the next morning before continuing our journey to Christmas Island.

At 4:30am local time, our plane landed at Christmas Island Airport. It was still dark when we were transported in four buses, travelling about 40 minutes, before finally arriving at the Detention Centre – the final destination for our next two weeks of quarantine.

The 40-hour evacuation journey was over.

4-16 February: Quarantine at Christmas Island Detention Centre

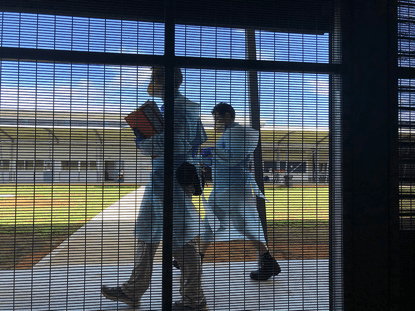

At the Christmas Island Detention Centre, the 238 Australian evacuees were housed in three major accommodation areas named Blue Block, Green Block and Gold Block. AUSMAT staff were allocated in White Block. Each block contained two identical wings equipped with a number of rooms and one playground. Each block was isolated from the others by fences and security walls.

AUSMAT staff informed us of the four essential rules:

- The only place we did not need to wear facemask was our room;

- We were free to go out of the block, but should not be beyond the restriction area called Oval, where the quarantine hospital was set up;

- Outside our rooms, we should always keep at least one meter away from others, even if we talked to each other; and

- Different family groups should not sit at the same table outside their rooms.

These rules were important to prevent potential virus transmission between evacuees.

I was allocated a single room in Block Green 1. It was a small room but contained everything one would need: a bathroom, a single bunk bed, a desk with a small colour TV, a fixed chair, a small refrigerator and a narrow cabinet. The room was clean. On the bed there was a mattress, pillow, blanket and sheets provided. I was also given 10 N95 medical facemasks and some toiletries.

When I entered the room, I felt a bit depressed because the room looked more like a cell, especially as the window was blocked by metal mesh-wire.

But the unpleasant feeling did not stay with me for long.

We received a sincere welcome from the Army and AUSMAT staff. They provided most supplies to accommodate our daily requests. In the next couple of days, army staff brought in food, books, children’s toys and sport equipment.

In each block, there was a communal kitchen area, where the army staff delivered our meals and other supplies.

Food provided for evacuees were sufficient and of certain varieties, though lacking of vegetables and fruits. As the island only has about 1000 residents, the local vegetables and fruits were not enough to supply more than 400 evacuees and supporting staff. Most of our foods and supplies were transported by air from mainland Australia.

After settling down at the Detention Centre, passing the time became the next issue for many evacuees. Once a person is confined to a restricted space, the challenge becomes psychological in nature.

From 5 February, my days were structured around a predictable routine. At 5:30am, in the quiet darkness of the morning, I got dressed and went to the oval to walk and take photographs. After breakfast, I did some research work and wrote in my diary. Lunch was at 12:30pm, after which I took a nap.

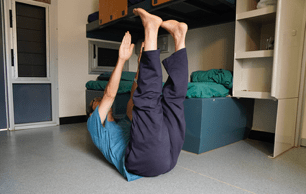

In the afternoon, I read books on my iPad; Bill Bryson’s book In A Sunburned Country and Joe Tasker’s classical mountaineering book Savage Arena. Indoor fitness training exercises became an important part of my day, both for my physical well-being and mental health.

Our dinner was served at 5:30pm. After dinner, I would go to the oval again to take photographs. Many evacuees took evening strolls around the oval during this time, which created interesting and unique compositions for me to photograph.

Surprisingly, I did not feel bored at all by going to the oval two or three times a day to take photographs. In fact, each time I found something fresh to shoot. Taking photographs also became an important part of my time on Christmas Island.

In particular, I was fascinated by the Christmas Island red crabs. These large, red crustaceans would sometimes find their way through the carefully constructed fences and appear on the oval. One day, I even found one in my room.

The biggest issue was the poor Internet connection, especially in the first week of quarantine. Many adult evacuees found it very hard to spend their time without the Internet, as it was a way to stay connected to the outside world.

For myself, I think the living conditions on Christmas Island were not perfect, but good enough. I was grateful to the Australian government for undertaking the evacuation operation.

17 February: Going Home

Luckily, no one tested positive for coronavirus. After 13 days in quarantine, we were able to go home. Three charter flights had been arranged by Qantas to send the 238 evacuees to the capital cities in Australia.

Army staff arranged a farewell BBQ for us in the early morning of 17 February. For most of us, it was strange seeing each other for the first time without a facemask. I said goodbye to the other evacuees whom I had gotten to know in the last two weeks and thanked the Army and AUSMAT staff who had supported us during this time.

At 6:20am, we were arranged into 10 mini buses which headed to Christmas Island Airport. It was an exciting time for us. The bus ride to the airport was the first time we saw Christmas Island in broad daylight outside of the Detention Centre where we’d spent the past two weeks.

I was on the first flight which took off at 8:20am. The plane stopped over at Port Hedland in Western Australia for 45 minutes to refill and then continued its journey.

At 7:45pm, the plane landed in Sydney Domestic Airport.

At last, I was home.

______________________

Yan Zhang is a professor at Western Sydney University and an award-winning photographer and mountaineering enthusiast. In January 2020, Yan was at the epicentre of the coronavirus epidemic that struck the city of Wuhan. He was then evacuated from Wuhan through the Australian Government’s Evacuation Operation.