Cockatoo identified in 13th Century Vatican manuscript

RESEARCHERS HAVE IDENTIFIED four drawings of a cockatoo in a book about ornithology and falconry owned by Emperor Frederick II of Sicily, now held in the Vatican library. De Arte Venandi cum Avibus (‘The Art of Hunting with Birds’) was written between 1241 and 1244, meaning the illustrations pre-date other European depictions of the bird by 250 years.

The fact that the cockatoo made its way from Australasia to Italy suggests there was already a flourishing trade network between Australasia and Europe in the 13th century, according to Dr Heather Dalton, a historian at the University of Melbourne, who is a co-author of a paper about the finding published in the history journal Parergon.

The cockatoo was a gift from an Egyptian Sultan of the Ayyubid Dynasty to Frederick II, who was fascinated by birds and their behaviour. Heather said she believes the cockatoo was taken from its original habitat by boat to Java and then Canton, before travelling via the Silk Road to what is now Cairo.

Mistaken identity solved

The images of the bird have rarely been reproduced in print until now. A mistranslation in the 1950s meant it was misidentified as an umbrella cockatoo (Cacatua alba), which is native to Indonesia.

Dr Pekka Niemelä of the University of Turku in Finland and his colleagues at the Finnish Institute of Rome examined the manuscript to determine the exact species of the cockatoo. They believe it is either a triton cockatoo (a subspecies of sulphur-crested cockatoo) or a yellow-crested cockatoo.

© [2018] Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

The cockatoo would have come from either the far-north coast of Australia, Papua New Guinea or the islands east of The Wallace Line, which delineates Australian and South East Asian fauna. The Latin manuscript, which is illustrated with over 900 images, describes the bird imitating human speech, confirming that the illustration was drawn from a live model.

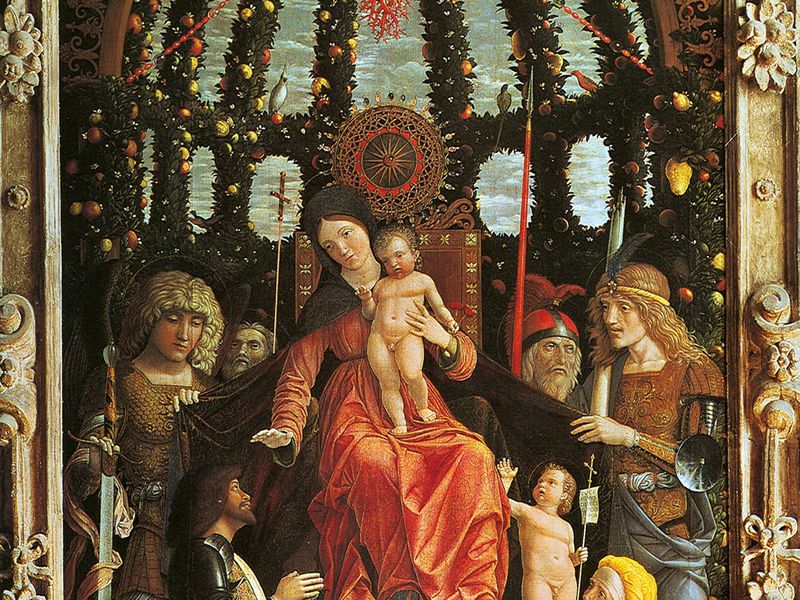

Previously, the oldest European depiction of a cockatoo was in an altarpiece artwork by Italian painter Andrea Mantegna from 1496. Heather had described Mantegna’s painting as evidence of the rich network of Australasian-European trade in a 2014 paper, which Pekka happened to come across in a Finnish history magazine. “This led to a very fruitful collaboration,” said Pekka. “It is an outstanding example of how historians and zoologists from opposite parts of the world can cooperate.”

“The waters to the North of Australia were busy with small craft in the 13th century, but most of the things traded have long disappeared,” added Heather. “This little parrot opens a window on a world we know little about.”

London-based historian Philip Parker, who is the editor of Great Trade Routes, said this recent finding provides a precious insight into the interconnections of the medieval world. “It really typifies the vital importance of trade routes […] at a surprisingly early date,” he said.