Hair is our ‘crowning glory’, the subject of songs and poems, Bible stories and even the eponymous 1960s musical. Everyone knows how important a ‘good hair day’ is – and how dreaded a ‘bad’ hair day.

Increasingly though, the hair that falls to the floor at your salon is becoming a key tool in helping the environment. Researchers have found hair to be a valuable resource that can be put to use soaking up oil spills, in water filtration systems to rid rivers and creeks of pollutants, as an alternative to chemical fertilisers, and as a potential source of graphite for use in lithium batteries.

“What makes hair truly special is that it’s a natural, infinite resource,” says Paul Frasca, founder of Sustainable Salons, a profit-for-purpose organisation dedicated to diverting hair salon waste from landfill.

Sustainable Salons collects hair clippings from more than 1400 salons and pet groomers across Australia and New Zealand, and is also the recipient of hair from the 12,000-plus Australians who shave, cut or colour their hair each year for the Leukaemia Foundation’s fundraising event, the World’s Greatest Shave.

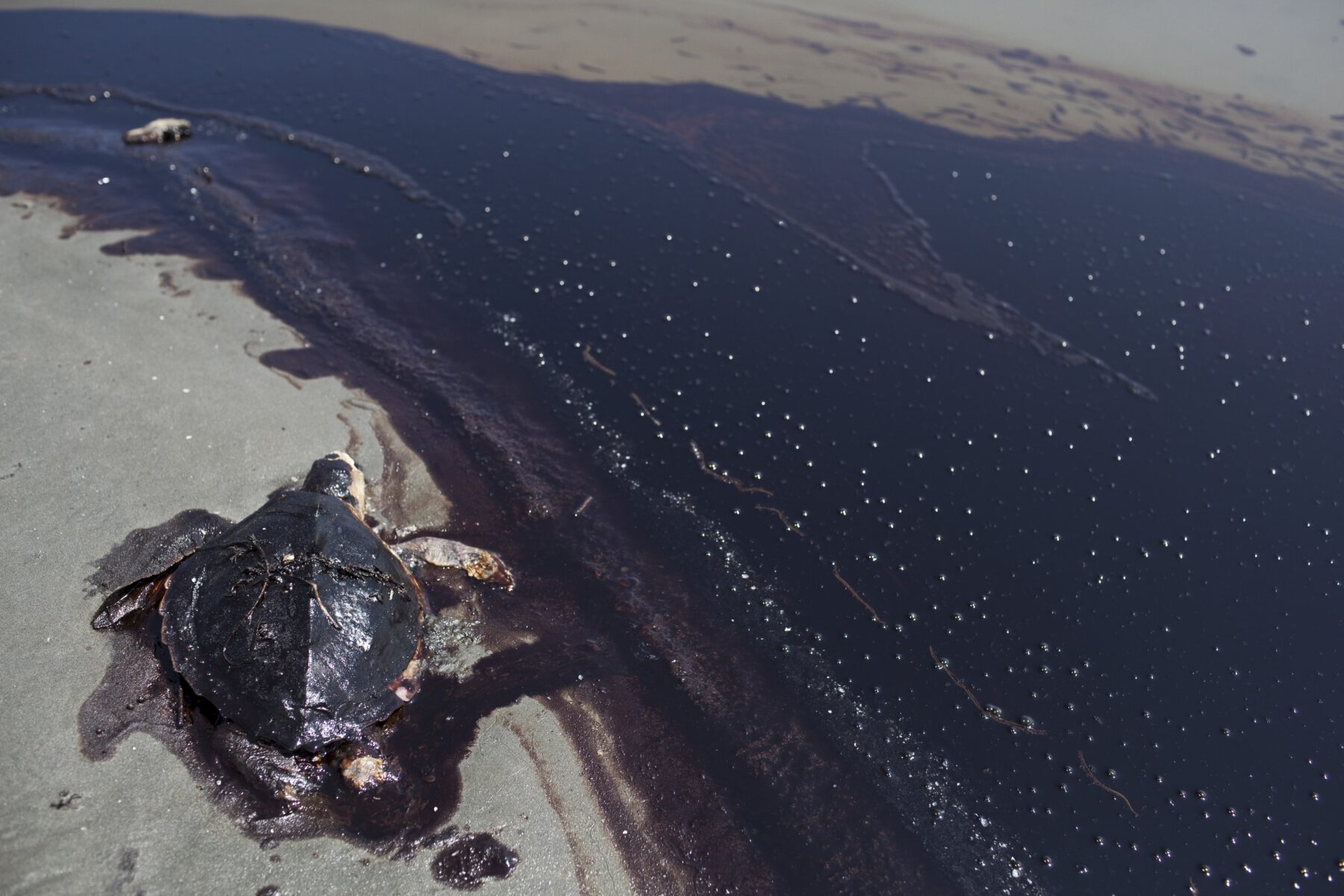

Founded in 2011, Sustainable Salons is the brainchild of Paul Frasca and Ewelina Soroko who had taken note of an environmental disaster in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, when an oil rig explosion leaked 795,000 litres of oil into the ocean per day. Hair clippings were collected and stuffed into nylon stockings, which were placed along beaches to soak up oil that washed ashore.

“As a former hairdresser, I’m a bit obsessed with what hair can do,” Paul says. “More than 500,000kg of hair ends up in landfill in Australia and New Zealand each year, and we began to wonder if we could do something with this idea and whether there was a commercially viable way forward for this amazing product.”

Hair booms: An organic alternative for soaking up oil spills

Plastic-heavy synthetic booms and chemical dispersants used in containing oil spills can have damaging long-term side effects on the environment. But research conducted in partnership with scientists at the University of Technology Sydney found that ‘hair booms’ – those aforementioned stockings stuffed with hair – were a natural resource that proved more effective in keeping waterways clean.

“Researchers we worked with at UTS found that 1kg of hair could remove 840g of spilled oil from seawater,” Paul says. “A standard hair boom is an organic alternative that can soak up to 4 litres of oil and can be drained and reused two more times.

“Land oil emergencies can come from things like trucks spilling oil, industrial leaks and construction site disasters. All of this seeps into the soil, and if we can find a way to use hair booms on land, we can eliminate the contamination, the plastic waste and the hazardous disposal problem.”

Image credit: courtesy Sustainable Salons

An early test for the use of hair booms in Australia occurred in July 2021 when a tanker rolled on the Great Northern Highway in Western Australia, spilling 28,000 L of oil. The spill spread into the creek system at Kirkalocka Station, 500km from Perth, impacting local wildlife, including turtles, yabbies, insects and birds. Sustainable Salons shipped 1000 hair booms containing more than 1200kg of hair clippings to Kirkalocka Station to assist in the clean-up.

Hair booms are also proving their worth in urban environments – for example, with the completion this year of a trial project to introduce them to stormwater systems.

Working with Willoughby City Council in New South Wales, green infrastructure company Urban Renew has improved water quality and flow rates in city stormwater systems by using hair booms to intercept pollutants before they enter rivers and oceans.

“Hydrocarbons are the number-one pollutant in run-off, mainly from tyres, fuel and oil spills on roads,” says Urban Renew director and project manager Angus Rex. “Hydrocarbons bind to hair, but water doesn’t, so the boom captures the pollutants and allows the water to flow through.”

Angus says that following the successful Willoughby trial, the technology was now being considered by other councils around Australia and in Singapore, as well as by mining companies.

Powering the future with hair

Hair clippings are also being used to research the potential for human hair, animal hair and wool to be used as a power source. Researcher Dr Amandeep Singh Pannu has spent the past five years investigating how these fibres can be turned into graphite for use in lithium batteries. Sustainable Salons provides the clippings collected from hairdressers and vets.

“Human hair and small offcuts of wool attached to sheep hide have little or no value and are a carbon-rich source that is readily available everywhere,” Dr Singh says.

“Hair is 50 per cent carbon, and under pressure and at a certain temperature – around 2000 to 3000°C – carbon turns to graphite, so we knew there was potential.

“My research showed that the synthetic graphite prepared with our reactor works better in lithium-ion batteries than natural graphite that is mined. However, there still needs to be more work done on the cost-effectiveness and scale of this process. The next step will be scaling up a reactor to make this a commercial reality.”

Dr Singh says prototype lithium-ion batteries had been produced using the graphite as one of the electrodes. Australia has a large supply of lithium, but needs to import graphite, a key component in lithium batteries. About 70 per cent of the world’s graphite comes from China.

Paul believes the potential for hair as a natural resource is vast. Other products in development include a new form of hair-based compost as a natural alternative to chemical fertilisers.

“Since 2015, we have collected more than 114,000kg of hair clippings,” he says. “The world will never be without hair, and growing and cutting hair doesn’t harm the environment or deplete other resources to do so.

“Hair is truly special.”