On this day in history: Albert Namatjira was born

BORN ON 28 July 1902, and originally named Elea, Namatjira received his western name – Albert – after his family joined the Lutheran Church when he was three.

From the Arrernte people, Albert grew up at the Hermannsburg Mission – then the largest mission in Central Australia, some 120km west of Alice Springs.

He took a variety of jobs as a young man, including blacksmith, stockman, carpenter and cameleer.

It wasn’t until Albert was in his late 20s that he met western artist Rex Battarbee, who ran a small exhibition of his own watercolours in Hermannsburg in 1936.

Inspired by the idea that he could earn a living from painting Albert joined Rex four years later, aged of 33, on a trip through the Northern Territory, where Rex taught him the art of watercolour and encouraged him to develop his, now, very recognisable style, a combination of European and Aboriginal influences.

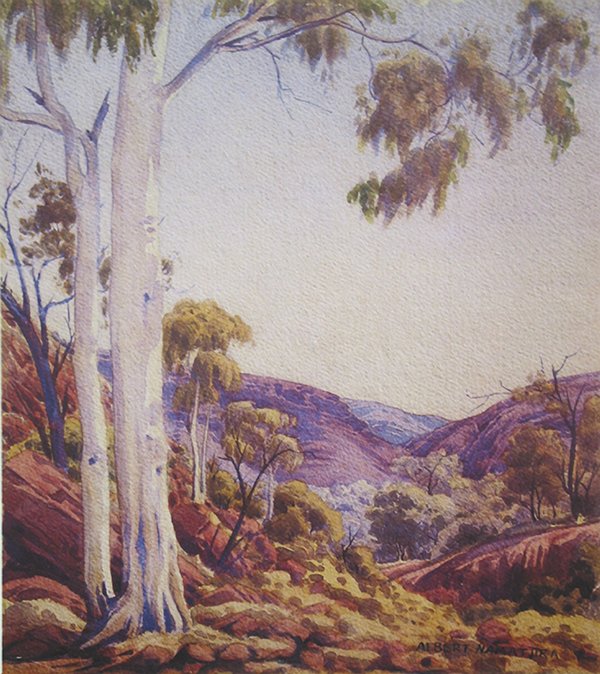

One of two reproductions by Albert Namatjira which were stolen from the Araluen Arts Centre in the Northern Territory in 2008. (Credit: AAP)

Albert Namatjira’s rapid rise

Albert’s fame took off quickly and stratospherically, alongside a growing debate about indigenous inequality; an evident talent that made him something of a figurehead to this nascent movement.

His first two exhibitions in 1938 in Melbourne and Adelaide sold out.

Judith Ryan, Senior Curator of Indigenous Art at the National Gallery of Victoria, says Albert won success in two hugely influential spheres: “He had a huge effect on Aboriginal art,” she says.

But he also “succeeded in the hardest place: the market,” says Judith. “His first two exhibitions sold out, which is a massive thing for any new artist – earning him a place in the living rooms of everyday Australians.”

Albert Namatjira: a man between two worlds

Albert was prolific, painting more than 2000 pieces (at least one-to-two a week for 25 odd years), determined to provide for his family in a way that few Aboriginal Australians at the time could dream of. However, life was not easy for the artist, who was caught between European and indigenous worlds for the latter half of his short life.

Nonetheless about 20 years after his first exhibitions he was being mobbed by autograph hunters in Sydney: “Crowds surged around him, many pushing notepads and paper at him, until the police reached him and escorted him to safety”, reported New South Wales’ Barrier Miner in 1954.

International accolades also flowed: Queen Elizabeth II awarded him a coronation medal in 1953. He met the Queen a year later when she visited Canberra.

The Royal Art Society of New South Wales also made him an honorary member in 1955, despite the fact that at the time indigenous people didn’t have full citizenship rights.

Namatjira’s death and legacy

He and his wife, Rubina, were granted citizenship in 1957, an entitlement not extended to all Aboriginal people until 1967. Citizenship gave Albert the ability to vote, own land and build a house. It also gave him the right to buy alcohol, a privilege that would come to be his downfall.

Albert’s duel worlds would, in time, clash tragically. It was common tradition to share good fortune with family, which Albert did by providing alcohol, a prohibited act. In 1958 he was charged with ‘supplying alcohol to an Aboriginal’, after a woman in his camp was killed in a drunken fight.

He was found guilty of breaking the prohibition laws and sentenced to three months of imprisonment.

He appealed in the High Court and the sentence was downgraded to two months of separation on the nearby Papunya settlement. He was released early due to health issues and died of heart failure on 8 August, 1959, aged 57. Eight years later indigenous Australians were given the right of full citizenship.

Albert Namatjira’s artwork and his high-profile life raised the issue of the unequal treatment of Aboriginal people in Australia.

Today, his work is on display at the National Gallery of Australia and even his small paintings command tens of thousands of dollars, one selling in 2006 for a record $96,000.

But more familiar to many Australians are reproductions of his prints that can be found on living room walls all over the country, alongside the likes of Australia’s other great landscape painters like Hans Heyson and Frederick McCubbin.

- Albert Namatjira’s ghost gums burned down

- 96-year-old wins top indigenous art award

- Waterhouse art prize won by Aboriginal artist

- Aboriginal art aims for the stars