Beware the dragon: this NSW nudibranch will mess you up

Bec Crew

Bec Crew

NAMED Pteraeolidia ianthina, it’s one of a handful of nudibranch species that harbour enough venom to give us humans a nasty sting. Just as the ridiculous-looking Glaucus atlanticus can pack a punch like a bluebottle, P. ianthina will make you regret stepping on it with bare feet.

But once the pain has subsided, you might appreciate how it got to be so weaponised.

The beauty of this tiny blue dragon is that it gets all of its powers from microscopic creatures that get inhaled into the nudibranch’s body, and then set up shop within, like a strange little airbnb.

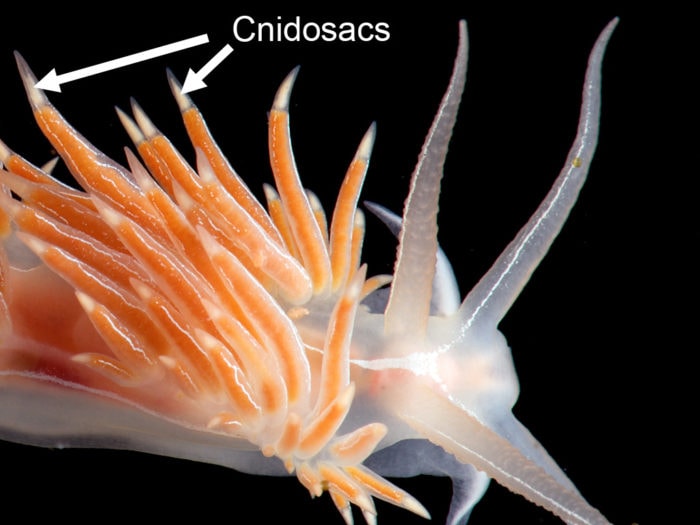

- Ianthina is a form of aeolid (pronounced eh-o-lid), a group of nudibranchs that possess fleshy projections known as cerata, which contain cnidosacs – small sacks that contain stinging cells called cnidocytes.

That’s a lot of words none of us will remember in 5 minutes, so let’s do it the easy way. These tips contain the bad stuff:

Image credit: Bernard Picton/Flickr

What’s genius about P. ianthina and other aeolids is that it doesn’t produce any toxins on its own, so in order to make itself distasteful to predators, it steals its toxins from its food.

- ianthina loves to feed on tiny predatory creatures called hydroids – jellyfish-like creatures that live in colonies and use stinging cells in their tentacles to capture even smaller prey.

Nudibranchs, with their ability to fire slime projectiles at predators and prey alike, are able to disarm the hydroids long enough to consume them. Once ingested, some of these unfired stinging cells (cnidocytes) pass through the nudibranch’s digestive tract and get stored in the cnidosacs.

While there are a bunch of species of aeolid sea slugs, only a few actually contain enough venom to bother a human – and P. ianthina is one of them.

A jellyfish-like hydroid. (Image credit: Ben Thompson/Flickr)

What’s extra cool about its hydroid-rich diet is that hydroids contain a type of microscopic organism called dinoflagellates, which are able to photosynthesise – even after they’ve been ingested by the hydroids, which are then ingested by the nudibranchs.

The sugars produced by this internal photosynthesis are enough to keep the nudibranchs going without feeding – which is particularly handy if food sources are few and far between.

While the cerata give these sea slugs their blue or purple colouration, the more dinoflagellates that are photosynthesising away in their gut, the more green or brown they appear.

For a long time, P. ianthina was thought to be widespread throughout the Indo-Pacific region, spotted in South Africa, Hawaii, Japan, and Australia. But a 2015 study revealed that what we’ve been looking at is actually a number of very similar-looking species.

The true distribution of P. ianthina, say Nerida G Wilson from the Western Australian Museum and Ingo Burghardt from the Australian Museum, appears to be restricted to NSW, Australia, from Port Stephens down to Eden.

“The identity of P. ianthina is clear,” they say, “and only applicable to the subclade known from temperate New South Wales, Australia.”

I don’t know about you, but I’m proud of our little blue guy. Here’s one doing what nudibranchs do best – cruising: