Kids, put down the snails

AROUND 5% OF common garden snails in and around Sydney, NSW, contain larvae of the parasite Angiostrongylus cantonensis, commonly known as the rat lungworm. It is probably more common in Brisbane and is seen on the coast from far north Queensland down to Jervis Bay, NSW.

The definitive hosts of this parasite are black and brown rats. That’s a significant problem for the rat – and for the snails and slugs (molluscs) that are infected when they come into contact with larvae in the rat’s faeces.

These larvae go through various developmental stages in the mollusc, and the cycle is completed when slugs and snails get eaten by rats.

The problem is, the slugs and snails can be accidentally eaten by dogs, wildlife species and humans.

Animals

Most domestic animal cases occur when dogs eat molluscs, which are often attracted to their food bowls. There is also some evidence that the mucus “slime trail” of snails contains infective larvae. Puppies are most commonly infected, perhaps because of their inquisitive and curious nature and indiscriminate eating habits.

Cats are not usually infected, because if they eat a snail, which isn’t likely because of their fastidiousness, they quickly vomit them up.

- Does Zika virus pose a threat to Australia?

- Watch out for bites from bats, experts warn

- Why your office is dirtier than your toilet

If a dog eats an infectious snail or slug, larvae leave the intestinal tract and make their way to the spinal cord at the tail-end of the dog, then migrate through the tissues of the nervous system, heading towards the brain. (The same thing happens in human patients.)

Affected dogs typically develop excruciating pain, which, in some cases, can be hard to locate. In others it is clearly felt in the neck and back. Vets must collect spinal fluid to make a definitive diagnosis.

There are good treatments for this disease, using cortisone-like drugs to dampen down the inflammation, and sometimes anti-parasitic drugs to kill the larvae burrowing through the spinal cord. Most but not all dogs respond favourably to therapy.

A tawny frogmouth with severe neurologic impairment due to a heavy rat lungworm infection. (Image: Author provided)

Not so lucky are tawny frogmouths and various other avian and mammalian wildlife species, including brushtail possums and flying foxes (macrobats). These also get infected through the ingestion of slugs or snails containing rat lungworm larvae.

Most affected wildlife die a slow and painful death as a result of these infections. They tend to ingest large numbers of larvae and their small spinal cord is easily damaged through parasitic migration.

Humans

Infections of dogs and wildlife species are important in their own right. But they also serve as useful sentinels for the possibility of human disease. Rat lungworm was first seen in dogs in Sydney in 1991, but not seen in human patients until 2001.

The clinical manifestations of neural angiostrongyliasis (the name of the disease in people caused by rat lungworm migrating through the spinal cord and brain) are just as devastating and tragic in human patients, especially if a baby or infant is infected.

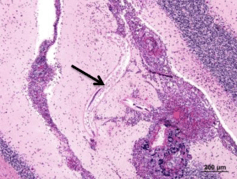

Microscopic appearance of A. cantonensis larvae (arrow) migrating through the brain of a brushtail possum. The same thing can be seen in affected human and canine patients. (Image: Author provided)

Several cases of neural angiostrongyliasis have been seen in Sydney and Brisbane, affecting both adult humans and infants.

Most affected children have been thought to eat slugs or snails, but it is possible that putting the snails in their mouth may have been sufficient to cause disease.

Adult humans can be infected if snails are left in vegetables used in a garden salad and ingested accidentally, and if people are foolish enough to deliberately swallow slugs or snails as a dare.

Despite the very best efforts of infectious disease clinicians and neurological teams at tertiary referral hospitals, some infected adults and children have suffered death or permanent brain impairment.

When it comes to this disease, prevention is better than cure. Here’s what you can do if you have children or a dog:

-

Control rodents in and around your house – hire a professional if need be. Use rodenticides in such a way, such as by using bait stations, that family pets do not become collateral damage. Don’t leave food and garbage around that attracts rats.

-

Control slugs and snails in the garden with pet-friendly molluscides. See your local vet for specific advice on what products are most suitable, and how to use them without risking intoxication of pets (or children).

-

Don’t let kids play with snails or slugs.

-

For dog owners, it’s likely that monthly preventative treatments for fleas and heartworm that contain moxidectin will prevent this disease. They’re not yet licensed for rat lungworm protection in Australia, but research from the United Kingdom suggests these treatments are effective.

-

Don’t leave dog bowls in places where they can be overrun with slugs and snails.

![]()

Richard Malik is a Veterinary Internist (Specialist) at the University of Sydney and Derek Spielman is a Lecturer in Veterinary Pathology at the University of Sydney.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.