To dam or not to dam?

This story first appeared in Australia Geographic magazine in January, 2008.

LOOKING LIKE SOMETHING FROM beyond our galaxy, Australia’s newest megadam straddles a gentle valley on the Burnett River, 260 km north-west of Brisbane. Apart from a soupy stain low on its upstream face, the concrete is spotless and dazzles the eye under the sharp Queensland sun.

This is Paradise Dam, completed in 2005. It’s named after another optimistic venture here, the goldmining settlement of Paradise, which flourished briefly around 1890. Standing on the dam wall is Dave Murray, who helped design it. Dave, 52, is tall, heavily built and bespectacled. He’s a senior dam engineer with Queensland Water Infrastructure (QWI) Pty Ltd, a corporation set up by the Queensland Government. Dams are Dave’s life. He’s good at his job and is proud of his engineering achievements, though he acknowledges large dams can be controversial.

The son of a travelling movie salesman, Dave graduated in civil engineering from the University of Queensland in 1975. He joined the then Water Resources Commission and worked on dams such as Burdekin Falls, Queensland’s biggest, completed in 1987. “It’s hard not to be proud of Burdekin Falls,” he says. “It’s hard not to say: ‘Hey, there I was at a little over 30 building the biggest water-supply dam we’reever likely to have in the State’.”

Looking along the Paradise Dam’s gleaming spillway, you’re immediately struck by its mass. This is no illusion: it really is massive. It contains 400,000 cubic metres of Roller Compacted Concrete (RCC), 40,000 cu. m of conventional concrete and 1 million tonnes of crushed rock. It’s Australia’s biggest RCC dam. Unlike conventional concrete, which needs 3-5 days to set, RCC can be built up non-stop in 30 cm layers, Dave says. “Each is compacted with small rollers so that it bonds with the layer below. When you’ve finished one, you put the next one down. It’s very quick.”

Like all large dams, Paradise is undeniably an astonishing feat of engineering. The wall is 920 m long and the spillway stands 37 m above the streambed. Built into the structure is a $5-8 million fishway that’s intended to transfer fish both up- and downstream. The dam is designed to hold back 300,000 megalitres (ML) of water (about a sixth of the water in Sydney’s Lake Burragorang) and create a 3000 ha lake 45 km long. When full, it will yield 124,000 ML a year for farmers (mainly Bundaberg sugarcane growers) and 20,000 ML for homes and industry.

But the weather has not been kind to Paradise. At the time of my visit last winter the reservoir was less than 10 per cent full, down from a high of 33 per cent. A trickle of 3-4 ML of water a day was being released downstream – hardly enough to operate the fishway effectively or run the 2.6-megawatt mini-hydro plant.

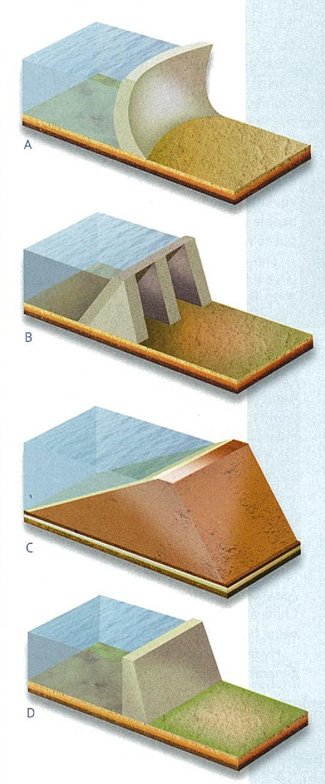

There are four types of dams in Australia.

A. Arch dams redirect a lot of pressure to the valley sides.

B. Buttress dams have 45 degree walls that transfer the force downwards.

C. Embankment dams, which are made of rock, gravel and sand, with the finest materials in the centre to form a waterproof core.

D. Gravity dams are thick, massive structures that can hold back enormous amounts of water under their own weight.

Damming attitudes

Measured across the continent, Australia receives an average of only 465 mm of rainfall a year, compared with Europe’s 640 mm and Asia’s 600 mm. High evaporation allows just 12 per cent of our rainfall to run off and reach waterways. Even so, there’s enough water for everyone – but it’s seldom in the right place at the right time.

European settlers solved this problem with dams. The first two – Yan Yean outside Melbourne and Lake Parramatta, Sydney – were completed in 1857. Dam building continued steadily until after WW II, when it accelerated. Today, 500 large (more than 15 m high) dams store a total of 93,957 gigalitres. (Sydney Harbour holds about 562 GL.) There are also countless smaller dams, called weirs, on most Australian rivers – 8000 in the Murray-Darling Basin alone – and more than 2 million farm dams.

Large dams bring quick benefits. They can provide water and electricity, mitigate flooding and create beautiful lakes. But they also have adverse impacts. The first are those on people living in the way of a dam and its lake. They may need to be moved, causing families and communities to fragment. The lake may flood farmland or natural landscape. Many of the drowned river’s plants and animals fail to adapt to lake conditions. Alien fish species, introduced into the reservoir accidentally or for recreational fishing, may further alter the biological make-up of water life; and weeds and algae may thrive in the nutrient-rich water.

Downstream, changes in the river’s flow and water quality usually cause irreversible effects, often down to the river mouth and beyond. Fish migration and reproduction, siltation and salinity in deltas are altered. Once upon a time, these adverse impacts – some of which take years to manifest – weren’t really considered before a dam was built. The human need for water, for drinking or to grow food, took precedence. Some people believe it should still. But over recent decades, science has deepened our understanding of natural systems, which we now know can’t be broken into discrete pieces, some of which can be exploited and others not. This has given rise to the idea that the environment itself is a legitimate water consumer, with attendant needs and rights. All this calls for careful study of a river’s state and function before it’s dammed.

“We need to consider rivers as ecosystems that provide goods and ecological services to society,” says Professor Angela Arthington, of the Australian Rivers Institute at Brisbane’s Griffith University. “That argument is becoming very powerful globally and is forming the basis of a lot of the negotiations about how you manage rivers and where you place dams – if you do place them.”

Impressive though it may be, Paradise, like other large dams, is a mix of good points and bad. For some people, the bad prevail. High among the complaints has been that the rationale behind it was political. In the 1990s, the idea of a dam on the Burnett River was dismissed as uneconomic, but former Queensland Premier Peter Beattie made it an election promise in 2000. Then there are the potential environmental impacts downstream, especially around the river’s mouth in Hervey Bay, which worry people such as commercial fishers and tourism operators.

But nothing has galvanised public opinion more than the plight of the endangered Australian, or Queensland, lungfish. Among the last of a group that lived 400 million years ago, this once-abundant fish is restricted mostly to the Burnett and Mary rivers. Biologists believe Paradise Dam has had, and will have, serious consequences for it. The fishway was installed to comply with the Commonwealth’s Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC Act), which lists the lungfish as endangered. The Act requires the fish’s spawning and nursery habitat to be preserved. Jean Joss, Professor of Biology at Sydney’s Macquarie University, says lungfish spawn in slow-flowing shallows with plenty of native water plants. “When it [Paradise dam] is full, it will have permanently destroyed 42 km of lungfish spawning/nursery grounds,” she says.

Growth of dams

Declining water consumption in most of Australia has stalled dam-building in recent years. But not in south-east Queensland. There, the population is set to soar from 2.8 million today to 5 million in 2050, and water consumption is expected to climb with it. The region mirrors not only what has happened historically elsewhere in Australia but also what’s happening across the world. Look here and you see humanity’s past and its future. South-east Queensland consumes about 440,000 ML a year. The Queensland Government says that by 2050 t he region will need 330,000- 490,000 ML more, even with water restrictions.

Prodded by drought but committed to economic growth, the government has assembled a mix of measures to provide the extra water. Among them are recycling, desalination, raising some existing dams and building two new ones – Traveston Crossing on the Mary River, and Wyaralong nearer to Brisbane. Peter Beattie said new dams were unavoidable and his successor, Anna Bligh, concurs: the dam at Traveston Crossing looks likely to go ahead. I visit the proposed dam’s Mary River site with Dave Murray, whose focus is appropriately professional. He tells me that turtles as well as fish trying to negotiate Traveston Crossing dam are catered for in the project’s design, which incorporates a turtle ramp as well as a fish transfer system. Dave seems to delight in such engineering challenges.

“If I commit to doing it, I want to make it work. I want to see turtles crawling up there,” he says. With a sweep of his arm, he shows where the dam would sit, stretching 1.6 km across the shallow valley 1 km upstream from Traveston Crossing, a popular picnic spot. QWI would build the dam in two stages. ‘Stage 1, due by 2011 and costing $1.6 billion, would flood 3000 ha of farmland and 334 properties; Stage 2, due after 2035, would raise the total cost to $2.5 billion and flood an extra 7135 ha and 265 properties. The dam wall would be RCC, Dave says, and at its western end it would merge with an earth-and-rock embankment.

Since one aim of the dam is to limit flooding in Gympie, 20 km to the north, the spillway would have six floodgates. QWI aims to build the dam to Stage 2 height immediately so that the only extra work needed later to raise the water level by another 8.5 m would be the fitting of higher gates. Peter Beattie’s announcement of the dam on 27 April 2006 shocked local residents. As with Paradise, there was talk of political expediency, but the government insisted the looming water crisis allowed no choice.

In its Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on the project, published in October 2007, QWI maintained the dam was the cheapest option offering maximum water returns. On the environment it was upbeat, saying downstream impacts would be negligible and that it could manage the effects around the dam’s footprint such that wildlife might even be better off than now. As in the Burnett, the lungfish is central here. But in the Mary it’s joined by the Mary River cod and the Mary River turtle. Since all are listed under the EPBC Act, the project needs federal approval. A decision based on the final Environmental Impact Statement is due in mid-2008.

Jean Joss appears as upbeat as QWI about the lungfish’s fortunes in the event of approval – though she insists that having no dam would still be better. What buoys her is the government’s pledge to build a $35 million Freshwater Species Conservation Centre on the Mary. “Traveston Crossing is a disastrous dam for many other reasons, but as far as the lungfish is concerned, it’s only disastrous if they put the dam in and then do nothing,” she says. “So, if it can be managed to the benefit of the environment, you might be able to have your cake and eat it.”

Assuming all the initiatives to mitigate environmental impacts eventuate, the future may indeed be rosy after Stage 1. The EIS deals only with Stage 1. About Stage 2 – 30-odd years down the track on current plans – it says little. So Stage 2 remains an unknown: deepening the reservoir by 8.5 m would have ramifications, and these have been examined, but the findings are barely touched upon in the environment statement.

Dams drowning the valley

For Mary Valley residents, nothing will ever repair damage already caused to families and communities by the dam’s announcement and QWI’s buy-out of properties in the dam’s footprint. QWI acknowledges that stress, depression, social withdrawal, community disintegration and deep mistrust have resulted but says not everyone has suffered.

By late 2007, QWI had reached sale agreements for 65 per cent of the land it needs. Many people who sold have leased back their former properties and may continue to live on them for a time. One who hasn’t sold is Glenda Pickersgill. Glenda breeds cattle on 68 ha beside the Mary about 1 km upstream of the proposed dam site. Her house and land would vanish under water at Stage 1. The farm has been in Glenda’s family for 30 years and she has owned it for 20. She grew up in the area and as a child fantasised about living beside the Mary.

“When I was about l7, I pestered my dad, just kept saying, ‘We’ve gotta buy a block on the river.’ And he eventually bought this one. Then I bought it off him and it was only last year that I finally paid everything off.” A fit 47-year-old with a blonde -streaked plait over one shoulder, Glenda was devastated by the Queensland Government’s announcement. “I had these churnings in my stomach for two months. And sadness and tears and frustration because I believed the process of water resources planning should have involved the community and some warning.”

As a member of the Save the Mary River Coordinating Group, an anti-dam residents’ coalition, Glenda has thrown all her energy into getting information about the project into the community and rallying support for the campaign against it. About 5 km south of Glenda’s place is a cemetery catering to the nearby village of Kandanga, population 200. Outside the cemetery, a hand-painted sign proclaiming “DAM LEVEL” has been hammered into a tree trunk 2 m above the ground. Another sign nearby pleads “NO DAM, DON’T FLOOD US”. Other anti-dam protest signs dot the Mary Valley. In Kandanga, one beside the main street shows the projected water level after Stage 2. If it’s right, the lake will lap at the door of the general store. The signs cluster in greatest quantity and variety at Kandanga’s old railway station, used these days only by a historic steam train. There, an airy weatherboard shed has become the headquarters and public information centre of the Save the Mary River Coordinating Group.

The group’s chairman, Kevin Ingersole, 63, is a dynamic, semi-retired management consultant who, with his wife, Sharon, bought a property in the valley five years ago. At Stage 1 they would lose much of their land. Kevin is bitter but, like Glenda, he diverts his emotions into action. He considers the EIS and its associated documents to be a “magnificent sales pitch for building a dam”, and claims that the government has not demonstrated that the proposed dam at Traveston Crossing is the best long-term solution for south-east Queensland’s water-supply needs.

QWI’s documents certainly attempt to build a convincing case for the dam’s long-term economic importance to the region, emphasising increases in gross regional product, employment and business potential. QWI also claims that the dam’s long-term cost will be more than $200 million less than the “next best” water-supply alternative, a desalination plant. But to Mary Valley residents it isn’t just about the money. What irks them most is that water from the proposed reservoir would be pumped out of the area. Of the lake’s 153,000 ML at Stage 1, 70,000 ML would go out every year. At Stage 2 the lake would hold 570,000 ML and would yield up to 150,000 ML a year. Angela Arthington says the environmental consequences of such extraction, together with the flooding of a shallow valley, are predictable because they characterise all megadams in similar landscapes.

“The best way to ensure the ecological integrity of the river ecosystem is to maintain the present flow regime and the habitats and resources required by all species,” she says. “Thousands of publications in the global literature document the adverse effects of dams on river and estuarine ecosystems.”

But if darns are such a bad idea, what are the alternatives – and are they really going to cost as much as the Queensland Government claims?

In a 2007 report, the Institute of Sustainable Futures (lSF) at the University of Technology in Sydney outlined a suite of measures that, in combination, would make a new darn unnecessary. Many are already in use or are planned, such as desalination, recycling, domestic water tanks, water efficiency standards for water-using appliances and fixtures, and business water-saving programs. But the ISF envisages much greater and more effective use of them to both reduce demand and increase supply. Professor Stuart White, the lSI’s director, says the institute used the Queensland Government’s own statistics for its study. “The claim that the Traveston Crossing dam option is the cheapest doesn’t make sense,” he says. “It’s certainly not cheaper than extending the demand-management program.”

Dams: Heritage or progress?

Dr Eve Fesl is an elder of the Gubbi Gubbi people, the Mary Valley’s traditional owners. Her mother, Evelyn Monkland-Olsen, was born beside the river, which her people call Mumabula. Eve was among Gubbi Gubbi leaders who rejected a $1 million State Government offer for signing an Indigenous Land Use Agreement . “By signing we would have agreed to the flooding of the valley,” Eve says. “No Aboriginal person worth their salt would swap their environment for money.”

Eve says Mumabula touches “our birth places, the sacred pools and spiritual places as she flows … In her womb she bears Dala, who, like a whisper from a long forgotten past, symbolises the wisdom of our elders … ” Dala is the lungfish, which Eve’s people were forbidden to kill. They knew instinctively it was special. So special, she believes, that there’s no question that the Federal Government should stop the dam. Deep down she’s confident Traveston Crossing dam will go the way of the 1983 Franklin dam proposal, which was stopped by a determined environmental campaign and Federal Government intervention. “I believe the spirits of my people will be behind us and help us save the Mary Valley,” Eve says.

Source: Australian Geographic, Issue 89 (Jan – Mar, 2007)

RELATED STORIES