Australian breakthroughs: the cervical cancer vaccine

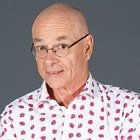

Dr Karl Kruszelnicki

Dr Karl Kruszelnicki

WAY BACK IN medical school I decided that my favourite organ was the uterus. That’s because it does its amazing job with a very high success rate – and only very occasional assistance from us. The cervix forms the bottom of the uterus, and bulges into the top of the vagina. Unfortunately, it’s susceptible to cervical cancer. Because of its location, it’s possible to see and check the cervix for cancer.

The first diagnostic test for cervical cancer was the Pap smear. Back in the early 20th century, a certain Dr George Papanicolaou performed a Pap smear on his wife practically every day – for two decades. This was so they could learn what the normal cervical cells looked like during a typical menstrual cycle, from cycle to cycle, and, finally, from year to year. (George was honoured with his portrait on postage stamps and on the 10,000 drachma Greek banknote. His wife and intellectual collaborator, Andromache, was honoured only in 1969.)

Over the years, it was discovered that cervical cancer was caused by the human papilloma virus, or HPV. In 2010 there were 12,000 cases of cervical cancer in the USA, causing some 4000 deaths. Additionally, several hundred thousand women needed treatment for pre-cancerous lesions caused by HPV. Indeed, HPV causes more than 5 per cent of all cancers worldwide.

Knowing that an infectious disease caused this cancer meant we could make a vaccine. Unfortunately, there are more than 120 different types of HPV. Most HPV types cause benign warts, but 15–20 types can cause cancer. Two members of the family (HPV-16 and HPV-18) cause some 70 per cent of cervical cancers.

A team led by Australian scientist Professor Ian Frazer invented Gardasil, the first cervical cancer vaccine. It became available in 2006. Not only does it protect against HPV-16 and -18, it also offers protection against two other types of HPV (6 and 11) that cause genital warts.

Gardasil reduces pre-cancerous cervical lesions by 99 per cent. After many millions of doses distributed globally with more than 100 human clinical trials, Gardasil seems to be safe and provide protection for at least five years. In 2006 Ian was awarded Australian of the Year for his efforts.

SEE MORE: